Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Every so often I read a tweet or listserv post saying something like this: “If modern buildings were prettier there’d be less NIMBYism.” I always thought this claim was silly for the simple reason that in real-life rezoning disputes, people…

In the WSJ, Jeff Yass & Steve Moore play the world’s smallest violin for the poor homeowners who are sitting on more than half a million dollars of nominal capital gains and therefore cannot sell. If only that tiny number…

Sometimes, opponents of new housing claim that they aren’t really against all housing- they just want housing to be “gentle density” (which I think usually means “not tall”), or “affordable” (which I think usually means “lower-income housing”). Even if these…

In Chapters 2 and 3, Ellsworth tries to argue for supply skepticism- that is, the idea that new housing (or at least the high-end towers that she opposes)* will not reduce rents or housing costs. She has made some effort…

Every so often I read a ringing defense of anti-housing, anti-development politics. Someone on my new urbanist listserv recommended an article by Lynn Ellsworth, a homeowner in one of New York’s rich neighborhoods who has devoted her life to (as she…

I recently saw a tweet complaining that left-wing YIMBYs favored urban containment- a strategy of limiting suburban sprawl by prohibiting new housing at the outer edge of a metropolitan area. (Portland’s urban growth boundaries, I think, are the most widely…

I recently read about an interesting logical fallacy: the Morton’s fork fallacy, in which a conclusion “is drawn in several different ways that contradict each other.” The original “Morton” was a medieval tax collector who, according to legend, believed that someone who spent lavishly you were rich and could afford higher taxes, but that someone who spent less lavishly had lots of money saved and thus could also afford higher taxes. In other words, every conceivable set of facts leads to the same conclusion (that Morton’s victims needed to pay higher taxes). To put the arguments more concisely: heads I win, tails you lose. It seems to me that attacks on new housing based on affordability are somewhat similar. If housing is market-rate, some neighborhood activists will oppose it because it is not “affordable” and thus allegedly promotes gentrification. If housing is somewhat below market-rate, it is not “deeply affordable” and equally unnecessary. If housing is far below market-rate, neighbors may claim that it will attract poor people who will bring down property values. In other words, for housing opponents, housing is either too affordable or not affordable enough. Heads I win, tails you lose. Another example of Morton’s fork is the use of personal attacks against anyone who supports the new urbanism/smart growth movements (by which I mean walkable cities, public transit, or any sort of reform designed to make cities and suburbs less car-dominated). Smart growth supporters who live in suburbs or rural areas can be attacked as hypocrites: they preach that others should live in dense urban environments, yet they favor cars and sprawl for themselves. But if (like me) they live car-free in Manhattan, they can be ridiculed as eccentrics who do not appreciate the needs of suburbanites. Again, heads I win, tails you lose.

In New York City, one common argument against congestion pricing (or in fact, against any policy designed to further the interests of anyone outside an automobile) is that because outer borough residents are all car-dependent suburbanites, only Manhattanites would benefit. For example, film critic John Podhoretz tweeted: “Yeah, nothing easier that taking the subway from Soundview or Gravesend or Valley Stream.” Evidently, Podhoretz thinks these three areas are indistinguishable from the outer edges of suburbia: places where everyone drives everywhere. But let’s examine the facts. Soundview is a neighborhood in the Southeast Bronx, a little over 8 miles from my apartment in Midtown Manhattan near the northern edge of the congestion pricing zone. There are three 6 train subway stops in Soundview: Elder Avenue, Morrison Avenue, and St. Lawrence Avenue. Soundview zip codes include 10472 and 10473. In zip code 10472* only 25.7 percent of workers drove or carpooled to work according to 2023 census data; 59.6 percent use a bus or subway, and the rest use other modes (including walking, cycling, taxis and telecommuting). 10473, the southern half of Soundview, is a bit more car-oriented- but even there only 45 percent of workers drive alone or carpool. 41 percent of 10473 workers use public transit- still a pretty large minority by American standards, and more than any American city outside New York. In the two zip codes combined there are just 45,131 occupied housing units, and 24,094 (or 53 percent) don’t have a vehicle. In other words, not only do most Soundview residents not drive to work, most don’t even own a car. Gravesend, at the outer edge of Brooklyn over 12 miles from my apartment, is served by three subway stops on the F train alone: Avenue P, Avenue U and Avenue X. It is also served by […]

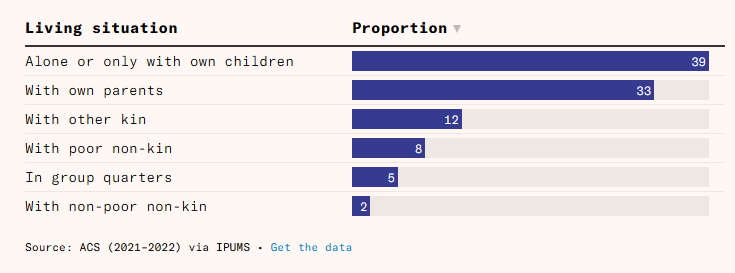

We can all understand the distinction between individual and systemic causes of homelessness. Can we apply the same rigor to potential solutions?

A new paper proposes that increasing diversity explains 90% of the recent decline in birthrates. Lyman Stone says it's nonsense.