Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

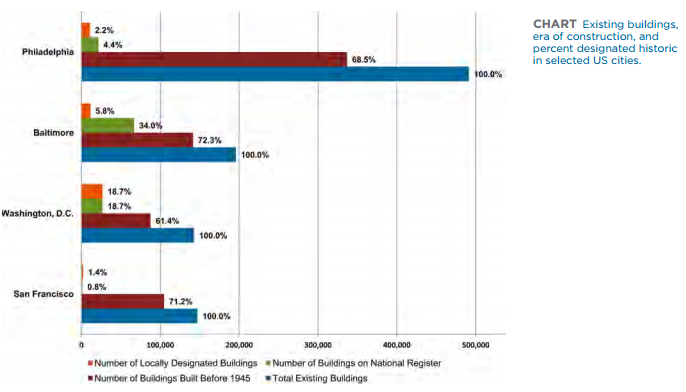

Historic preservation rules are part of the regulatory framework of most major American cities. But the historic districts in which they are generally applied get little inquiry from economists, meaning little is known about their nationwide scope and economic impact. And even between municipalities they can vary, depending on the precedents set by different circuit courts. Now the Cato Institute, a libertarian Washington think tank, is filing a brief that aims to bring consistency to these laws nationwide. In a 2014 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, a group of urban economists led by Ed Glaeser found that historic districts in New York City experienced less construction, and affected where in the city developers build. More importantly, the economists found that preservation laws were costliest in neighborhoods where redevelopment would have been most valuable. Another paper, published in 2016 by NYU, to mark the 50th anniversary of New York City’s preservation laws, explored the relationships between historic districts and the type of buildings built, the type of buildings preserved, demographics of the residents in historic districts, and more. The evidence presented in both studies suggests that historic districts do indeed alter the human geography of cities. It validates William Fischel’s observation that “historic districts thus operate as another example of the double-veto system that state land use regulations add to municipal regulation except that in this case the potential veto arrives prior to municipal review rather than afterward” (Zoning Rules!, Page 62). In Nectow v City of Cambridge, the Supreme Court held that Massachusetts violated due process by “arbitrarily and unreasonabl[y]” imposing restrictions on certain land, in a way that did nothing to protect the public (which was the original rationale for land use regulations under the earlier Supreme Court case Euclid v Ambler). That said, the rules about which historic […]

Hovering somewhere just beyond all the land use zoning regulations, building codes, finance mechanisms, aspirational comprehensive municipal plans, state mandates, and endless NIMBYism lies… reality. If you happen to want to live in certain parts of coastal California you need to come to grips with a serious supply and demand imbalance. Demand is endless. Supply is highly constrained. And there’s a huge amount of money on the table. Horizontal growth is essentially verboten. A powerful coalition of existing property owners, environmental groups, resource allocation schemes, and multi-tiered government regulations stymie new greenfield development. The personal interests of conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats line up exactly when anyone attempts to build anything near them. “Over my dead body.” It’s understood that if a town accepts endless low density horizontal development the overall quality of the area will decline. You can’t have expansive large scale suburbia without paving over the countryside, creating a great deal of traffic congestion, and inducing strip mall blight. At the same time, no one wants infill development on existing not-so-great property that’s already been paved over and degraded. The neighborhood associations break out the pitch forks and firebrands at the suggestion of multi-story condos or (Heaven forbid) apartment buildings. The population of any older suburb could double or triple without using a single inch of new greenfield land. But that kind of growth is feared and hated. So the aging muffler shops and parking lots linger in the middle of a massive housing crisis. Google Google Google On the other hand there’s radically less regulatory or community push back against expanding and improving existing suburban homes. Google Street View makes it possible to observe how a little post war tract home was transformed into a substantially larger residence. This kind of growth is entirely acceptable. The building […]

The Austin area has, for the 5th year running, been among America’s two fastest-growing major metro areas by population. Although everybody knows about the new apartments sprouting along transportation corridors like South Lamar and Burnet, much of the growth has been in our suburbs, and in suburban-style areas of the city. Our city is growing out more than up. How come? The desire for living in central Austin has never been higher. But Austin, like most cities, has rules that prevent new housing from getting centrally built. That makes it easier to buy and build on virgin land in the suburbs. Here are some of those rules. 1 MINIMUM LOT SIZE Historically, expensive houses were built on expensive, large lots; cheaper homes were built on smaller, cheaper lots. Austin decided that new houses can’t be built on small lots. Even if you want to build a small, cheap house, you still need a lot with at least 5,750 square feet. In central Austin, that costs a lot of money, even without the house! If somebody owns a 10,000 square foot lot, they aren’t allowed to split it into two 5,000 square foot lots and build two medium-sized houses, let alone three 3,333 square foot lots with three small houses, let alone three 3,333 square foot lots with triplexes! In 1999, Houston reformed its minimum lot size laws. Since then, environmentally-friendly central-city urban townhomes have flourished. 2 MINIMUM SITE AREA For areas that are zoned for apartments and condos, there is a cap on the ratio of number of apartments to lot size known as “minimum site area.” 3 IMPERVIOUS COVER MAXIMUMS Impervious cover is any surface that prevents water from seeping into the ground, including buildings, driveways, and garages. There is a cap on the ratio of impervious cover to lot size. 4 FLOOR-TO-AREA RATIO MAXIMUMS Floor-to-area ratios (aka FAR) maximums are a cap on […]

To market urbanists and many others, it’s clear that there is a positive relationship between high housing costs and land-use restrictions and that liberalizing zoning would lower housing costs relative to what they would be in a more regulated environment. Given this relationship, reducing zoning would improve efficiency in the housing market by allowing consumer demand to drive the amount of resources that are put into housing development. However, land-use reform would also affect other policy areas such as public schools, transportation infrastructure, and sewer and water provision. Predicting how a liberalizing reform in one policy area will affect the complete public policy landscape is as impossible as predicting how one private sector innovation will affect other markets. Political scientist Steven Teles coined the term “kludgeocracy” to describe the complexity of contemporary American policy. For example, zoning has become a tool to make high-performing public schools exclusive, even though land-use policy and education policy are seemingly unrelated areas governed by different agencies. Because providing zero-price quality education to every child in the country may be impossible, zoning is a kludge that allows policymakers to provide this service to their high-income and influential constituents. Teles describes this policy complexity: A “kludge” is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “an ill-assorted collection of parts assembled to fulfill a particular purpose…a clumsy but temporarily effective solution to a particular fault or problem.” The term comes out of the world of computer programming, where a kludge is an inelegant patch put in place to solve an unexpected problem and designed to be backward-compatible with the rest of an existing system. When you add up enough kludges, you get a very complicated program that has no clear organizing principle, is exceedingly difficult to understand, and is subject to crashes. Any user of Microsoft Windows will immediately grasp the concept. […]

Cato recently kicked off an essay series they’re calling “What Can’t Private Governance Do?”. The series questions how far we can take private governance in replacing public institutions. The most recent essay by Mark Lutter questions where to draw the line between private and public in territorial governance. And, more importantly, whether drawing that line even makes sense. Mr. Lutter concludes that it does, but I’ll politely disagree. We should instead abandon the public vs private dichotomy. It doesn’t accurately describe reality. It’s not useful for understanding policy problems. And it distracts us from the more interesting lines of inquiry we could otherwise be pursuing. A Tale of Two Cities Imagine two different cities, one proprietary and the other public. The former is run as a private, for-profit firm. It has an executive team, board of directors, and shareholders. The latter is a traditional municipal corporation. It’s run partially by elected officials and partially by appointees. It’s what we would call non-profit. No one “owns” the government as a legal entity. Now imagine that both cities raise revenue through land values. Greater demand to live in either city translates into a higher price for land. And the more that either city does to make their jurisdictions attractive, the more revenue that either stands to collect. In this scenario, price signals in the form of land valuations give both cities an incentive to make positive sum investments. Those same price signals also provide both cities with the ability to understand what those positive sum investments might be. Each city is responding to price information and making positive sum investments. So what difference does it make to call one public and the other proprietary? In all fairness, there’s still one place we could draw a line. We could make the choice of […]

Housing has a lot going against it in the California. But amidst all the legal, political, and regulatory roadblocks, there’s one law that sneaks by largely unnoticed: Prop 98. Prop 98 guarantees a minimum level of state spending on education each year. Sacramento pools most city, county, and special district property taxes into special education funds to meet this commitment. The localities only get to keep a small part of the property tax revenues for their own general budgets. This system creates a disincentive for cities to permit housing. New housing brings in new residents who need city services. But it doesn’t bring in a commensurate increase in property taxes since most of that revenue gets scooped up by Sacramento. Commercial development, though, brings in taxes a city gets to keep. Sales and hotel taxes are significant revenue streams. And they don’t cause the kinds of strain on city services that new residential does. Reforming Prop 98 might be low hanging fruit. Changing the formula to appropriate a broader stream of city revenues might help ease the bias against housing. And it might even be possible to amend the law without having to fight the California Teachers Association. As long as there’s no net decrease in education funding, of course. It’s tough to say exactly how much new housing Prop 98 actually prevents. Different cities get to keep different amounts of their property taxes, so the disincentive differs case to case. And there are plenty of other things like CEQA and Prop 13 which put a drag on new construction as well. But where CEQA and Prop 13 make it easier for residents who are already NIMBYs to gum up the works, Prop 98 is a reason in itself for a city to avoid residential development. So while we can’t do […]

This post draws heavily from Tom W. Bell’s “Want to Own a City?” and would not have been possible without his prior writing and research The “Right to the City” is an old marxist slogan that’s as catchy as it is ill-defined. Neither the phrase’s originator Henri Lefebvre, nor David Harvey, a more recent proponent, seem to have articulated the idea in any meaningful way. Even the Right to the City Alliance stops short of explaining what the right actually is. When it comes up, it’s typically alongside a claim that something is being stolen or taken away from long-standing communities, as if neighborhoods were sovereign territory suffering from an invasion. For practical purposes, no one has any right to reside in any place beyond their ability to pay. But if the desire is for a way in which communities could actually own the places they call home, perhaps the Right to the City should be a property right. Public Ownership through Private Property What’s the difference between a private company and a municipal corporation? You can own the former but not the latter. Investors have clearly delineated property rights in their corporations. Residents have no equivalent ownership rights in their cities. But what if living in a city meant owning a piece of it as a legal entity as well? Imagine that a city issued shares to its residents. Shares would vest over time and long-time residents would have more equity than new arrivals. Now assume that this city took in all of its revenue through land value taxation and that land revenues were used to pay dividends to the city’s resident-shareholders. Instead of facing displacement, incumbent residents would benefit from rising demand to live in their city. Shares might also be used to weight the voting system. More shares could […]

The destruction of inner cities at the hands of bureaucrats wielding eminent domain has been well documented by urban theorists from Jane Jacobs to Richard Epstein. As Ilya Somin points out, eminent domain has played an important role in destroying property in Detroit, contributing to its population losses. Dating back to the implementation of Title 1 of the Housing Act of 1949, urban policymakers began using federal funds for slum clearance. Unsurprisingly, destruction of housing units correlated with the population decline in Detroit and other cities. While one would think that the horrors of slum clearance under Title 1 have been adequately demonstrated to prevent planners from pursuing neighborhood destruction as an economic growth strategy, cities across the country continue using eminent domain to clear “blighted” neighborhoods. Last year Denver declared an area of its Five Points neighborhood, including 246 homes, blighted, meaning that now developers interested in building in the area can request the city to use eminent domain to grant them the properties that they want. While the Atlantic Yards project received extensive press coverage, policymakers often employ eminent domain more quietly on behalf of stadium builders, benefiting sports fans at a dear cost to neighborhood residents and business owners. Like urban renewal projects dating back to the 1950s, Forest City Ratner has failed to deliver the promised housing that was part of the Atlantic Yards agreement when the city agreed to condemn the neighborhood. Perhaps Robert Caro provides the most poignant description of the horrors of eminent domain in The Power Broker, explaining the losses of neighborhood cohesion when the tool is used to demolish private housing to be replaced by public housing or in some cases vacant lots when promised public works are not delivered. One would think that the well-documented failures of urban renewal would lead policymakers […]

I recently spoke with George Mason University Law Professor David Schleicher about his research on land use law and economics. Here is our conversation including links to some of his academic articles that have earned a lot of attention in the land use blogosphere. Emily: What are some the costs of land use restrictions? Talk about agglomeration economies and how these relate to development restrictions. David: This is a huge area of research that spans back to Alfred Marshall looking at why cities exist in the first place. It comes up with explanations for why people are willing to pay increased rents to live downtown. These include lower transportation costs for goods, which was a major driver of urbanization for much of American history. Today this is a small driver of urbanization because the costs of internal shipping have fallen so dramatically. Now an important advantage of urbanization is market size. You can see this in all different markets. Restaurant rows are a great example of this. When you go to one of these rows where there are a lot of restaurants and bars, you have insurance that if one place you go is bad, you know you have other options nearby. The last category of agglomeration benefits is learning, or information spillovers. We see this in cluster economies like Silicon Valley where people at different firms learn from each other. As Marshall explained, “The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries, but are as it were in the air.” Wage growth is faster in urban areas than in rural areas, and this comes from this learning process. In the aggregate, if you keep people out of dense cities, you will decrease national productivity. Emily: In your paper City Unplanning, you propose a tool called Tax Increment Local Transfers (TILTs) that would compensate property owners for allowing more development […]

It sounds like a dumb question – they exist because people like the security of owning a home combined with the services and lower costs that apartments offer, duh! But upon further reflection, condominium-style tenure can be a bit problematic. The main problem, as I see it, is that a building that’s been carved up into condo units can almost never be redeveloped. So much so that preservationists have been known to cheer on developers doing condo and co-op conversions of historic properties: Indeed, sometimes preservation advocates look to condo developers as white knights. Since the Bialystoker Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation on East Broadway closed last year, Laurie Tobias Cohen, the executive director of the Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy, has been “extremely eager” for a developer to buy the historic building and convert it to co-ops or condos. The closing of the nursing home was a great loss, she said; the goal now is to prevent the demolition, or further deterioration, of the building. “What we don’t want,” she said, “is to lose any more of the built historic fabric.” This is no doubt an elegant solution to the problem of unprotected historic buildings, but what about the less-than-stunning condos and co-ops that have been built in the US – and pretty much every where else in the world! – since the end of World War II? Why are condo buildings impossible to redevelop? Simple: gravity! You can’t keep your apartment on the 17th floor while someone demolishes their 5th floor unit. In Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore, they call condos “strata” apartments, which reflects what they really are: floors of apartments layered inseparably atop each other. To redevelop a condo or co-op building, you have to buy every single unit, after which you can dissolve the condo structure […]