Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

It is because every individual knows little and, in particular, because we rarely know which of us knows best that we trust the independent and competitive efforts of many to induce the emergence of what we shall want when we see it. — Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty Imagine the perfect city. If you have a clear picture in mind, you’re not alone. Tsars, emperors, and prophets have been trying to build perfect cities for millennia. With the emergence of the field of urban planning and modern social science, everyone from stenographers to industrialists to independent architects have joined in. For Ebenezer Howard, the perfect city was the Garden City, a corporate-owned residential satellite on the outer edge of town. For Le Corbusier, it was the Ville Radieuse, full of “skyscrapers in the park” and elevated highways. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was Broadacre City, a dispersed anti-city full of single-family homes on one-acre lots. Each reflects a distinct vision of urban life, and each seems to have as many opponents as it does proponents. Thankfully, few of these plans have ever been implemented in full on a mass scale. Yet “perfect city” thinking—the view that one particular vision of urban form should be imposed by planners—has manifested itself in small ways in cities around the world through the construction and enforcement of specific theories of how a city should work. This approach to urban form involves expanding urban planning beyond prudentially managing infrastructure and mitigating destructive negative externalities and toward enforcing and preserving particular lifestyle and aesthetic preferences. Consider: while Ville Radieuse was never built, many cities bulldozed traditional urban neighborhoods to construct the urban elevated highways of Le Corbusier’s dreams. While Broadacre City never moved beyond the model stage, many suburban communities still zone minimum lot sizes […]

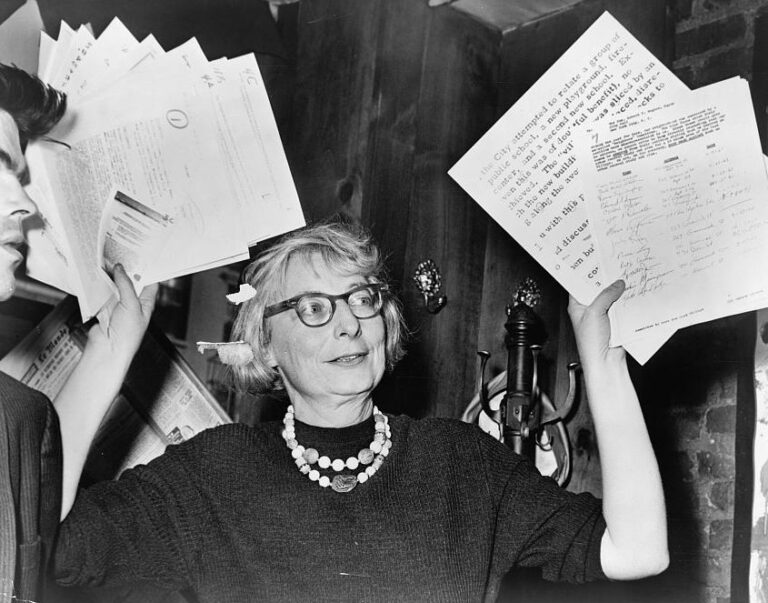

Jane Jacobs (May 4, 1916 – April 25, 2006), one of the most important and influential public intellectuals of the twentieth century, died a few days shy of her ninetieth birthday. The intellectual legacy she left for social theorists is as significant as that of anyone else of her generation. She was the author of nine books, including The Economy of Cities (1969), Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1984), The Nature of Economies (2000), and her most famous work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). She also published an article in the prestigious American Economic Review (“Strategies for Helping Cities,” September 1969). Most are surprised to learn that she held only a high-school diploma and began her book-writing well past the age of 40. In her first book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs argued that the urban planners of her day, infected by the top-down collectivist ideology that was the conventional wisdom among nearly all intellectuals, ignored the perspective of ordinary people on the street. Her position, radical for its time, was that real cities don’t conform to one person’s or group’s aesthetic ideal because visual order is not the same as actual social order. She argued that complex social orders, such as a city, begin with ordinary people forming informal relations with one another in the neighborhoods in which they live, play, or work. Such networks emerge and thrive when people are able to have free and casual contact with acquaintances and strangers alike in the safety of streets, sidewalks, and other public spaces. But most of that safety is achieved not by aggressive formal policing but by voluntary recognition and informal enforcement of local norms. The key is for each neighborhood or city district to have sufficiently diverse attractions at […]

This week on the Market Urbanism Podcast, I chat with Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring on the wonderful new volume Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs. From Jacobs’ McCarthy-era defense of unorthodox thinking to snippets of her unpublished history of humanity, the book is a must-read for fans of Jane Jacobs. In this podcast, we discuss some of the broader themes of Jacobs’ thinking. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Pick up your copy of Vital Little Plans on Amazon. Mentioned in the podcast, Manuel DeLanda discusses Jane Jacobs in A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. Read more about the West Village Houses here. The question of Quebec separatism is a fascinating—and under-considered—element of Jacobs’ work. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities is a short, often wonderful but consistently enigmatic (at least to me) novel about an extended conversation between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan. Marco tells the Khan a series of tales about fantastical cities he’s perhaps only imagined. I’ve always assumed that the book’s title refers to that imaginary quality, since no one besides Marco himself has actually seen the cities he describes, and they likely exist only in his mind or in the words as he utters them. Recently, I hosted a couple of group “tours” of my neighborhood. These tours are called “Jane’s Walks” in memory of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs. In the course of explaining her (mostly laissez-faire) principles to the group, I realized there’s another interpretation of Calvino’s title that I much prefer. It is this: A city—especially a great one—cannot really be seen. Paradoxically, the closest we can come to actually seeing one is through the imagination. Otherwise, it’s invisible. Moreover, if you can fully comprehend a place, then it’s not a city. You Don’t See a City on a Map If you think about a particular city that you know, what comes to mind? An image, a feeling, a smell, or a sound? Before we visit a city, we may look at pictures of parts of it, perhaps its famous landmarks, but these mean little to us in themselves. We may study a map of Paris to get a sense of the layout or the general shape of the metropolis. But what we are seeing is not the city of Paris but something highly abstract, abstracted not only from Paris but also from the particular reality of our lives. If, before going there, we could somehow look at a photo we will take of Paris, the scene would not evoke much from us […]

Why are a growing number of libertarians fascinated by cities and indeed pinning their hopes for a freer future on cities? Two examples of this just from recent Freeman issues are by Zachary Caceres on startup cities and the winner of the Thorpe-Freeman Blog Contest, Adam Millsap, responding to one of the articles in an entire cities-themed issue. There is a deep affinity between cities and markets, and indeed between cities and liberty. (As the old saying goes, “City air makes you free.”) Cities aren’t merely convenient locations for markets; a living city (which I’ll define in a moment) is a market, and the first cities probably originated as markets. Much has been written on this connection, but I’d like to point out another link between cities and markets—one that comes from the great 20th century urbanist, Jane Jacobs. Consciously or not, Jacobs followed the tradition of the influential German sociologist Max Weber in seeing cities as essentially markets. Indeed, in her 1969 book The Economy of Cities, she defined a city, or what I like to call a “living city,” as “a settlement that consistently generates its economic growth from its own local economy.” Moreover, I’ve written elsewhere that today’s economic phenomena of demand, supply, the price system, markets, externalities, public goods, and division of labor had their genesis in an urban setting. The fundamental (classical) liberal concepts of property rights, economic freedom, and the rule of law did not develop among wandering nomads, farmers, or in small villages but perforce from the interactions of strangers with diverse cultures and backgrounds interacting in dense proximity with one another. Diversity… In her great book of 1961, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs first presented her argument that the key feature of any great city is its diversity. […]

My guest this week is Sanford Ikeda, a professor of economics at SUNY Purchase and a visiting scholar at New York University. He has written extensively on urban economics, policy, and planning. Professor Ikeda introduced me to urban economics and urban planning when he gave a presentation on Jane Jacobs at a FEE summer seminar that I attended back in 2012. Here are a few of the topics we discussed in the episode: If you haven’t already, I highly suggest reading Jane Jacobs. The natural place to start is The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Her other books, including The Economy of Cities and Systems of Survival, explore topics ranging from economics to political philosophy. Professor Ikeda has written extensively on Jane Jacobs. You can read a nice overview here. If you would like to read more, click here for a paper he wrote on F.A. Hayek, Jane Jacobs, and the importance of local knowledge in cities. He is also a regular contributor to Freeman and Market Urbanism. We also discussed William H. Whyte’s famous documentary on public space, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. It’s well worth checking out. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

This week’s column is drawn from a lecture I gave at the University of Southern California on the occasion of the retirement of urban economist Peter Gordon. One of my heroes is the urbanist Jane Jacobs, who taught me to appreciate the importance for entrepreneurial development of how public spaces—places where you expect to encounter strangers—are designed. And I learned from her that the more precise and comprehensive your image of a city is, the less likely that the place you’re imagining really is a city. Jacobs grasped as well as any Austrian economist that complex social orders such as cities aren’t deliberately created and that they can’t be. They arise largely unplanned from the interaction of many people and many minds. In much the same way that Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek understood the limits of government planning and design in the macroeconomy, Jacobs understood the limits of government planning and the design of public spaces for a living city, and that if governments ignore those limits, bad consequences will follow. Planning as taxidermy Austrians use the term “spontaneous order” to describe the complex patterns of social interaction that arise unplanned when many minds interact. Examples of spontaneous order include markets, money, language, culture, and living cities great and small. In her The Economy of Cities, Jacobs defines a living city as “a settlement that generates its economic growth from its own local economy.” Living cities are hotbeds of creativity and they drive economic development. There is a phrase she uses in her great work, The Life and Death of Great American Cities, that captures her attitude: “A city cannot be a work of art.” As she goes on to explain: Artists, whatever their medium, make selections from the abounding materials of life, and organize these selections into works […]

Henry George and Jane Jacobs each have an enthusiastic following today, including, I’m sure, some readers of The Freeman. For those who might not know, Henry George is the late-19th-century American intellectual best known for his proposal of a “single tax” from which he believed the government could finance all its projects. He advocated eliminating all taxes except that on the rent of the unimproved portion of land. He viewed that rent as unjust and solely the result of general economic progress unrelated to the actions of landowners. Jane Jacobs, writing about one hundred years later, is an American intellectual best known for her harsh and incisive criticism of the heavy-handed urban planning of her day. She advised ambitious urban planners to first understand the microfoundations of urban processes — street life, social networks, entrepreneurship — before trying to impose their visions of an ideal city. Much has been written, pro and con, on George’s single tax and also on Jacobs’s battles with planners the likes of Robert Moses, and if you’re interested in those issues you can start with the links provided in this article. Here I would like to contrast their views on the nature of economic progress and the significance of cities in that progress. Some interesting parallels There are some interesting parallels between George and Jacobs. Both were public intellectuals who rebelled against mainstream economic thinking — for George it was classical economics, for Jacobs neoclassical economics. Both had a firm grasp of how markets work, were critical of crony capitalism, and concerned with the problems of “the common man.” And both established their reputations outside of academia. George was a strong advocate for free trade and an opponent of protectionism. He also understood Adam Smith’s explanation of the invisible hand. As George writes in […]

Since new urbanists (in my experience) tend to be very skittish of high-rise development, one might think that their ideological ancestor Jane Jacobs was one of these people who thought no building should be over five floors. But in her 1958 essay “Downtown Is For People,” she hinted at a very different view, describing New York City’s Lever House and Seagram Building as among the city’s “extraordinary crown jewels.” Similarly, she described San Francisco’s Union Square (which bordered buildings of wildly varying heights) as “the city at its best.” Jacobs was not against height–but she was against monotony. She wrote, for example, that Park Avenue should “have the most commercially astute and urbanite collection possible of one- and two-story shops, terraced restaurants, bars, fountains and nooks.” So I’m not sure she would have favored the common modern idea that high-rise and low-rise buildings should be segregated from each other, or that buildings of different density are “out of scale.”

The Philadelphia Housing Authority will seize nearly 1,300 properties for a major urban renewal project in the city’s Sharswood neighborhood. The plan includes the demolition of two of the neighborhood’s three high-rise public housing buildings — the Blumberg towers — that will be replaced with a large mixed-income development. The new buildings will increase the neighborhood population tenfold with the majority of the new units to be affordable housing. The majority of the 1,300 lots slated for eminent domain are currently vacant. At a City Council hearing on Tuesday, Philadelphia Housing Authority CEO Kelvin Jeremiah testified that the redevelopment plan furthers the agency’s efforts to replace high-rise housing projects with lower-density units. However, PHA’s plan misses the forest for the trees. The benefits of demolishing the two towers are immediately undone by creating an entire neighborhood of public housing, effectively increasing the concentration of poverty in Sharswood. Adam Lang has lived in Sharswood for 10 years, and he posted about the plan in the Market Urbanism Facebook group. Adam has raised concerns that the PHA does not have an accurate number of how many of the 1,300 properties in the redevelopment territory are currently occupied. Adam’s primary residence is not under threat of eminent domain, however he owns four lots that are. He uses two lots adjacent to his home as his yard. The other two are a shell and a vacant lot. He purchased them, ironically, from the city with the plan to turn them into rentals. Adam’s concern about the inaccuracy of PHA’s vacancy statistics stem from the method that PHA employees used to create their estimate: driving by homes to see if they look occupied or not. Adam’s own property was on the list of vacants, and he said that he’s aware of other properties in the neighborhood […]