Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In my last post I critiqued the introduction to Lynn Ellsworth’s new anti-YIMBY book, Wonder City. Having just finished Chapter 1, I thought I would add my thoughts. Ellsworth seems to be primarily motivated by a fear of something called…

Jane Jacobs wasn’t optimistic about the future of civilisation. ‘We show signs of rushing headlong into a Dark Age,’ she declares in Dark Age Ahead, her final book published in 2004. She evidences a breakdown in family and civic life, universities which focus more on credentialling than on actually imbuing knowledge in its participants, broken feedback mechanisms in government and business, and the abandonment of science in favour of ‘pseudo-scientific’ methods. Jacobs’ prose is, as always, rich, convincing and successful in making the reader see the importance of her claims. Yet the argument that we are spiralling into a new Dark Age, similar to that which followed the fall of the Roman Empire, is not quite complete and I remain unconvinced that the areas she identified point towards collapse as opposed to merely things we could, and should, work to improve. Let us start with the idea that families are ‘rigged to fail,’ as she puts it in chapter two. Jacobs, urbanist at heart, cites ‘inhumanely long car commutes’ stemming from the disbanding of urban transit systems, rising housing costs, and a breakdown in ‘community resources’ – the result of increasingly low-dense forms of urban development – as a significant reason why families are now set up for failure. She suggests our days are filled with increasingly vacuous activities, leading to the rise of ‘sitcom families’ which ‘can and do fill isolated hours’ at the expense of ‘live friends.’ That phenomenon has now been replaced by the ‘smartphone family’ where time spent on TikTok, and consuming other forms of digital media have supplanted the ‘sitcom’ family of the past. There has been significant literature on the detrimental effects of digital technologies to our physical and mental health, not least in Jonathan Haidt’s most recent book, The Anxious Generation. A similar picture is painted by Timothy Carney in […]

Continuing this series of book reviews on Jane Jacobs’ works, I now turn to Cities and the Wealth of Nations. But there is already a fantastic piece on the Market Urbanism website, by Matthew Robare, who reviews this book and outlines what Jacobs overlooks in her analysis. So, this piece takes a slightly different angle: inspired by (but not limited to) Jacobs’ ideas, it aims to highlight what mayors, governors and urban policymakers could do differently if they are serious about developing their cities into economic powerhouses. Here are some of the most important takeaways from this book and also how they can be expanded upon. (1) Focus on cultivating import-replacement The economies of cities do not grow out of nothing. They grow by adding productive new forms of work to old ones, by innovating, and by being cultivators of new ideas and techniques. This process of cataclysmic growth – that Jane Jacobs describes as ‘import-replacement – occurs when a city takes its existing imports and builds upon them, either improving its production through lowering costs, increasing quality, or innovating. The market for these additional goods can either be found within the city itself or serves to expand the city’s exports. These exports, in turn, bring in additional resources to either acquire additional imports or be reinvested into fuelling the processes that fuel import-replacement. Not for nothing does Jacobs describe import-replacement as a ‘cataclysmic’ process – these changes often happen over a very short period and can bring about a rapid influx of people, ideas and capital. We see this in New York City, which grew from half a million residents in 1850 to over 3.4 million at the dawn of the twentieth century. Detroit went from having 250,000 residents in 1900 to a peak of 1.8 million by 1950. […]

Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, revolutionised urban theory. This essay kicks off a series exploring Jacobs’ influential ideas and their potential to address today’s urban challenges and enhance city living. Adam Louis Sebastian Lehodey, the author of this collection of essays, studies philosophy and economics on the dual degree between Columbia University and SciencesPo Paris. Having grown up between London and Paris, he is energised by the questions of urban economics, the role of the metropolis in the global economy, urban governance and cities as spontaneous order. He works as an Applied Research Intern at the Mercatus Center. Since man is a political animal, and an intensely social existence is a necessary condition for his flourishing, then it follows that the city is the best form of spatial organisation. In the city arises a form of synergy, the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, for the remarkable thing about cities is that they tap into the brimming potential of every human being. In nowhere but the city can one find such a variety of human ingenuity, cooperation, culture and ideas. The challenge for cities is that they operate on their own logic. Cities are one of the best illustrations of spontaneous order. The city in history did not emerge as the result of a rational plan; rather, what the city represents is the physical manifestation of millions of individuals making decisions about where to locate their homes, carry out economic transactions, and form intricate social webs. This reality is difficult to reconcile with our modern preference for scientific positivism and rationalism. But for the Polis to flourish, it must be properly understood by the countless planners, reformers, politicians and the larger body of citizens inhabiting the space. Enter Jane […]

It’s an understatement to say that zoning is a dry subject. But in a new video for the Institute for Humane Studies, Josh Oldham and Professor Sanford Ikeda (a regular contributor to this blog) manage to breath new life into this subject, accessibly explaining how zoning has transformed America’s cities. From housing affordability to mobility to economic and racial segregation to the Jacobs-Moses battle, they hit all the key notes in this succinct new video. If you need a go-to explainer video for the curious new urbanists, this is the one. Enjoy!

At first blush, the enterprise of interpreting the Jane Jacobs’ work might seem like one best left to the proud and peculiar few, or to put it less charitably, those of us with nothing better to do. Yet the forces of history militate against this apathy: Jane Jacobs has emerged as quite possibly the most important figure in North American urban planning in the second half of the twentieth century. Her work is now taught in every urban theory and urban planning program worth its weight in ESRI access codes. She is responsible for introducing hundreds of thousands of people to planning and urbanism (including this author) and continues to shape how many of us think about cities. In one of my more popular blog posts here on Market Urbanism—and in a forthcoming book chapter—I argue that we should interpret Jane Jacobs as a spontaneous order theorist in the tradition of Adam Smith, Michael Polanyi, and F.A. Hayek. Built into her work is a profound appreciation of the importance of local knowledge, decentralized planning, and the spontaneous orders that structure urban life. Needless to say, this is not the prevailing interpretation of the importance and meaning of Jacobs’ work. Two very different alternative interpretations prevail. In this post, I argue that both interpretations are mistaken. Jane Jacobs, Form-Based Coder Many have taken Jacobs’ particular critiques of conventional U.S. zoning, often referred to as “Euclidean zoning,” as motivating a new form of zoning that takes into account her observations on design. In contrast to the mandates of Euclidean zoning, which proscribes land-use segregation and low densities, Jacobs celebrated mixtures of land uses and urban densities. Jacobs spends large sections of Death and Life discussing in detail particular urban designs that she sees as essential to fostering urban life. Much of “Part One” focuses on […]

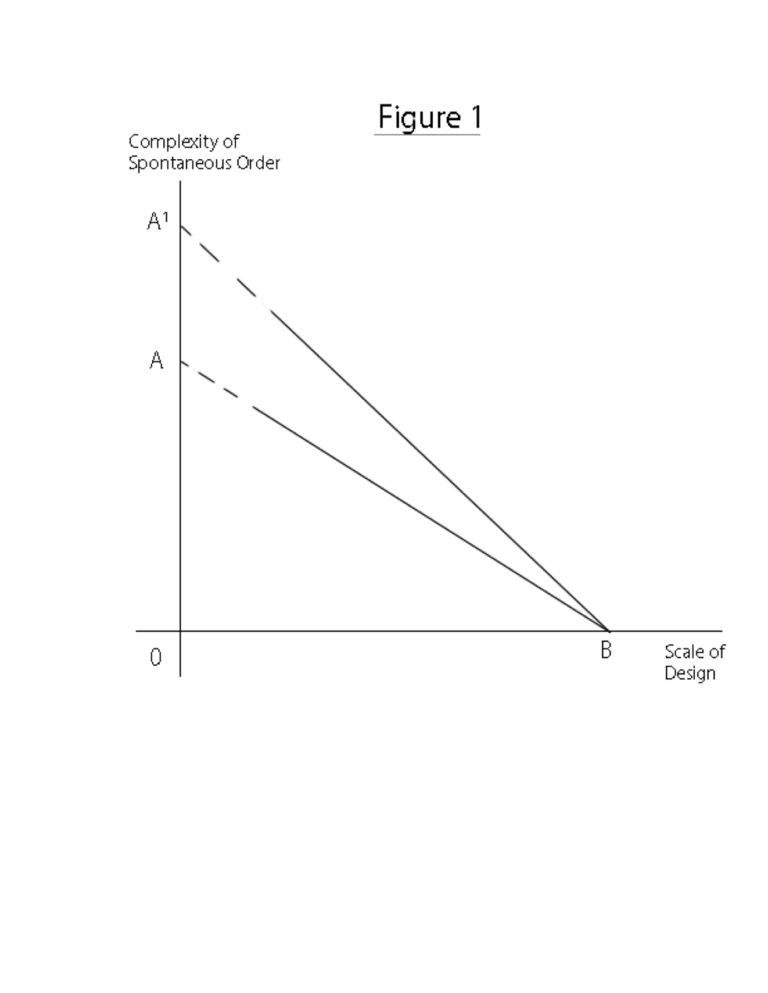

Viewing cities as spontaneous orders and not as works of art helps to explain the tradeoff between scale and order, as well as the role of time in softening the severity of that tradeoff. Complexity and creativity are at odds with scale and the comprehensiveness of design because increasing scale impinges on the action spaces where creative, informal contact tends to happen. Design might complement that informal contact to a point, but beyond a fairly low level it begins to overwhelm it. Again, small is not always beautiful, and big is sometimes unavoidable. That makes it all the more important to understand the impact of scale and design on spontaneous social orders. That applies as much to private as it does to public projects. When the designs are small relative to the surrounding social milieu, the downside of the tradeoff isn’t very steep. The problems start when budget constraints are soft and projects become mega-projects and mega-projects become giga-projects. I don’t want to sound too ideological – Jane Jacobs somehow avoided being ideologically pigeonholed all her life – but soft budget constraints are primarily the domain of governmental and, especially, of so-called public-private developments: Those elephantine-starchitectural-wonder-complexes that too-often strive for off-the-charts wow-factors. Without legal privileges, subsidies, and eminent domain, could the scale and degree of design of purely privately funded developments even begin to compare to those? I don’t think so. The rules of the game of urban processes interact in complex ways. So deliberately changing some of those rules to achieve a particular outcome is akin to trying to impose a particular design on the social order, killing the social order in the process, although perhaps preserving the appearance of life. Taxidermy again. (That, by the way, is why I have problems with landmarks preservation on the scale practiced […]

Before we can correct what we think is wrong with a city, we need an appropriate standard of what is right. That standard of rightness in turn depends on our understanding how the thing we are trying to fix is supposed to work. In this regard I’m afraid neither standard macroeconomics nor microeconomics is much help at all. In traditional macroeconomics, too much important detail is lost in its pre-occupation with aggregates and averages. For example, standard macroeconomic theory treats capital as homogeneous, and so makes no distinction between a hammer and a harbor, except that a harbor may be the equivalent of many, many hammers. Such an approach is too blunt an instrument for getting to the level of detail needed to appreciate the complex time-structure of capital of an economy, let alone to tell us what would be necessary to promote that structure (Lachmann 1978). Jacobs expressed antipathy toward macroeconomics. Macro-economics—large-scale economics—is the branch of learning entrusted with the theory and practice of understanding and fostering national and international economies. It is a shambles. Its undoing was the good fortune of having been believed in and acted upon in a big way (Jacobs 1984: 6-7) Earlier in this Chapter we saw that, unlike a living city, a nation-state is not a natural unit of economic analysis. In Jacobs’s words: Nations are political and military entities, and so are blocs of nations. But it doesn’t necessarily follow from this that they are also the basic, salient entities of economic life or that they are particularly useful for probing the mysteries of economic structure, the reasons for rise and decline of wealth. Indeed, the failure of national governments and blocs of nations to force economic life to do their bidding suggests some sort of essential irrelevance (Jacobs 1984: 31-32). The […]

We can visualize the tradeoff between the scale of design and the complexity and spontaneity of a social order as a downward-sloping curve. A sort of “scale-versus-order-possibilities frontier.” In addition to scale and spontaneous order/complexity, a third element I would add to the tradeoff is the passage of time. You can to some extent plan for complementarity, but you can’t really plan for spontaneous complexity and intricacy. [Helpful to bring in capital theory here?] Fortunately, time allows people to some extent to adjust social networks and physical spaces to better complement their own plans, in ways that the designer could not foresee. That is, for any given scale, time lets people figure out novel uses for, or changes to, the space as originally designed. Those unthought-of uses constitute an increase in the level of complexity in a spontaneous order. Over time, then, the frontier can shift outward. Figure 1 reflects these relations: The scale of a structure and the designed or planned uses of the space within that structure are of course two different things. Increasing the dimensions of a room doesn’t necessarily mean the elements that go into its design become more complex. But to keep things simple, Figure 1 treats scale and design as highly positively correlated. [Is this necessary?] Thus, as scale increases so do the designed elements – you move from point A to point B – and together they decrease the potential for spontaneous order. [But think about the tradeoff between scale and order, keeping design constant. Just increasing scale does seem to increase the designed/planned element in a previously undesigned space.] Then, as time passes, the frontier shifts up from AB to A’B, where point B represents the case where the structure occupies100% of the relevant action space. So for any given scale, the […]

First of all, Jacobs observed that the artist abstracts from life, with all its “inclusiveness” and “literally endless intricacy.” Many architects, especially those with great ambition, seem to treat urban environments as merely a canvas for their works of genius, which if not already blank needs to be wiped clean before getting to work. The good ones at least try to take into account how their constructions fit or don’t fit into the existing built environment and how real people might actually use them. But whether you’re an architect or an economist, predicting how people will respond to a change is a pretty iffy thing. From my perspective that iffiness comes from two factors: complexity and radical ignorance. Complexity in this context means that the interactions among people are so numerous or varied or changeable that the costs of being aware of all of them is too high for anyone to calculate. Hayek defines the degree of complexity in terms of the “minimum number of elements of which an instance of the pattern consists in order to exhibit all the characteristic attributes of the class of patterns in question…” (Hayek 1964). In a world with only a few variables, such as those described in a high-school algebra problem, it is possible to have all the knowledge you need to get the correct answer. In the real world, however, the number of relevant variables is too large, that is the number of ever-changing interactions among people in society is so large, and our cognitive powers are too limited to do that. Compared to the vast complexity of the social order, predicting this week’s weather is a pretty simple matter. Radical ignorance means being unaware of information that would be relevant to making a decision, not because the cost is too high, […]