Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

We can all understand the distinction between individual and systemic causes of homelessness. Can we apply the same rigor to potential solutions?

An old dorm becomes a new shelter for homeless families in DC.

The conventional wisdom (based on Census estimates) seems to me that urban cores have lost population since COVID began, but are beginning to recover. But mid-decade Census estimates are often quite flawed. These estimates are basically just guesses based on complicated mathetmatical formulas, and often diverge a bit from end-of-decade Census counts. Is there another way to judge the popularity of various places? Perhaps so. I just uncovered a database of real estate price trends from Redfin. Because housing supply is often slow to respond to demand trends, housing prices probably reflect changes in demand. What do they show? First let’s look at the most expensive cities: San Francisco and New York City where I live now. If conventional wisdom is accurate, I would expect to see stagnant or declining housing prices in the city and some increase in suburbia. In Manhattan, the median sale price for condos and co-ops was actually lower in 2024 than it was in mid-2019, declining from $1.25 million in August 2019 to $1.05 million in August 2024.* Similarly, in the Bronx multifamily sale prices decreased slightly (though prices for single-family homes increased). By contrast, in suburban Westchester County, prices increased by about 30 percent (from just under 250k to 325k). Similarly, in Nassau County prices increased from 379k to 517k, an increase of well over one-third. So these prices suggest something like a classic suburban sprawl scenario: stagnant city prices, growing suburban prices. In San Francisco, by contrast, property values declined everywhere. City prices declined from $1.2 million in August 2019 to just under $1 million today; in suburban Marin County, the median price declined from $633k to $583k. So sale price data certainly supports the narrative of flight from expensive cities. What about places that are dense but not quite as expensive? But […]

Kevin Erdmann argues that mortgage credit standards are too tight. Others say the federal government is subsidizing homeownership. Can they both be right?

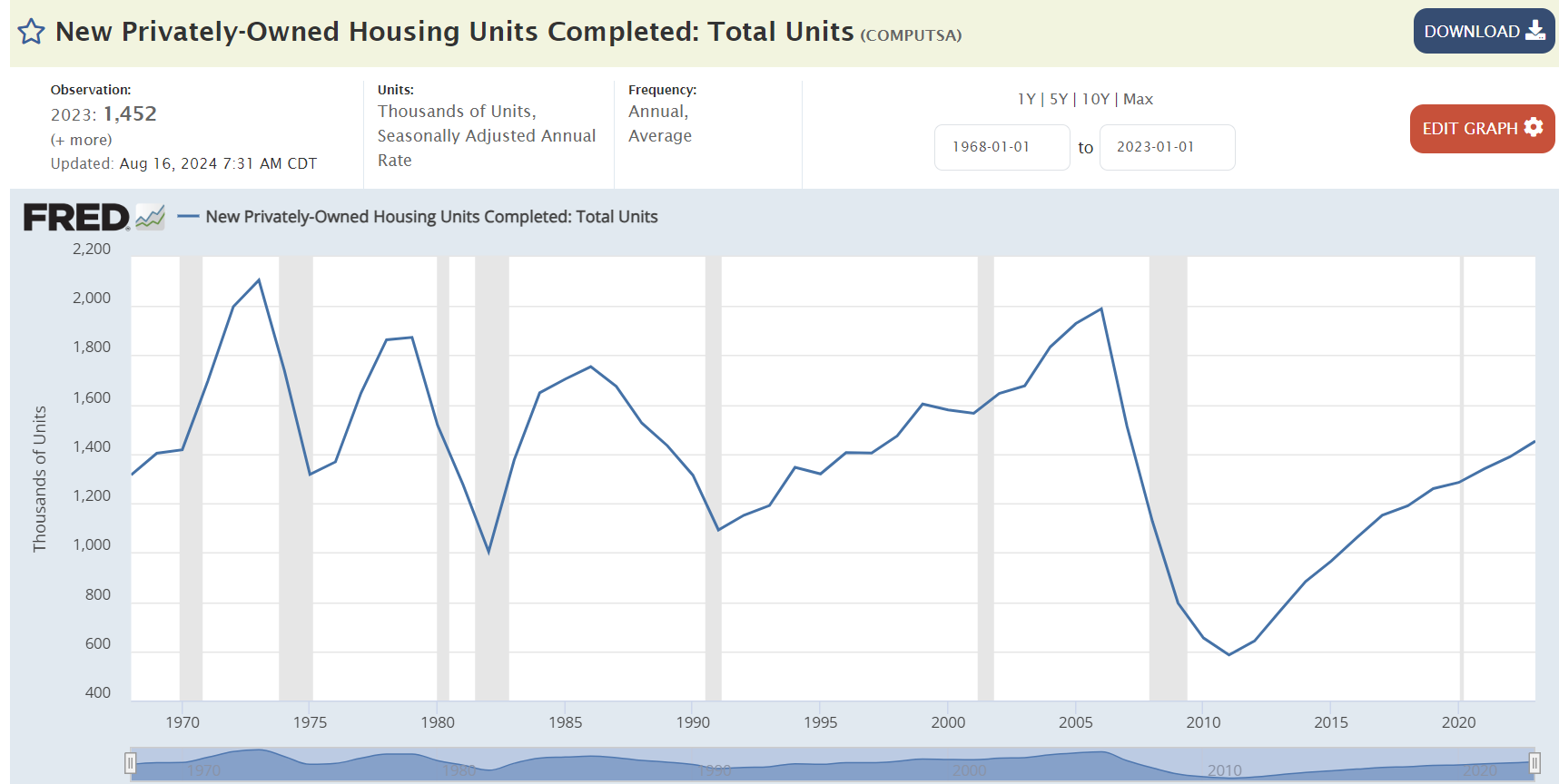

Kamala Harris has pledged to build 3 million new housing units. Setting aside the methods, what does that mean? And, would it "end America's housing shortage"?

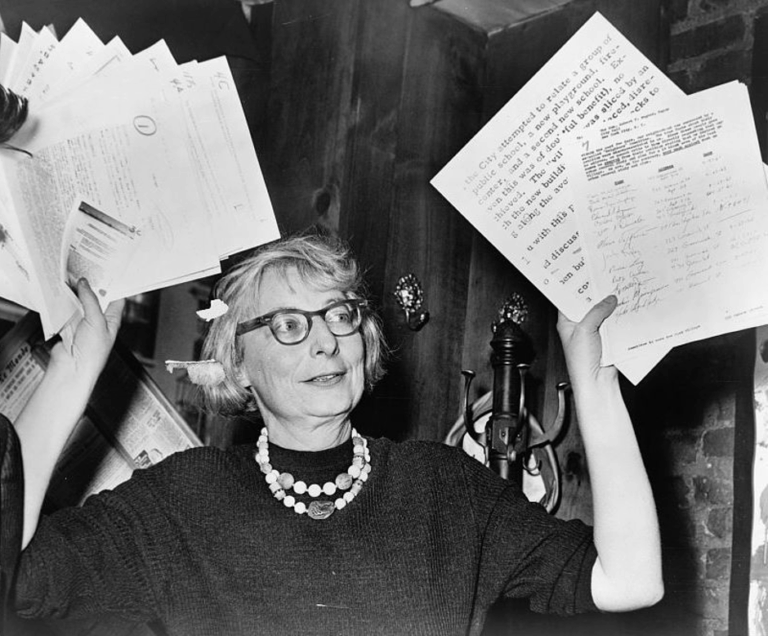

Continuing this series of book reviews on Jane Jacobs’ works, I now turn to Cities and the Wealth of Nations. But there is already a fantastic piece on the Market Urbanism website, by Matthew Robare, who reviews this book and outlines what Jacobs overlooks in her analysis. So, this piece takes a slightly different angle: inspired by (but not limited to) Jacobs’ ideas, it aims to highlight what mayors, governors and urban policymakers could do differently if they are serious about developing their cities into economic powerhouses. Here are some of the most important takeaways from this book and also how they can be expanded upon. (1) Focus on cultivating import-replacement The economies of cities do not grow out of nothing. They grow by adding productive new forms of work to old ones, by innovating, and by being cultivators of new ideas and techniques. This process of cataclysmic growth – that Jane Jacobs describes as ‘import-replacement – occurs when a city takes its existing imports and builds upon them, either improving its production through lowering costs, increasing quality, or innovating. The market for these additional goods can either be found within the city itself or serves to expand the city’s exports. These exports, in turn, bring in additional resources to either acquire additional imports or be reinvested into fuelling the processes that fuel import-replacement. Not for nothing does Jacobs describe import-replacement as a ‘cataclysmic’ process – these changes often happen over a very short period and can bring about a rapid influx of people, ideas and capital. We see this in New York City, which grew from half a million residents in 1850 to over 3.4 million at the dawn of the twentieth century. Detroit went from having 250,000 residents in 1900 to a peak of 1.8 million by 1950. […]

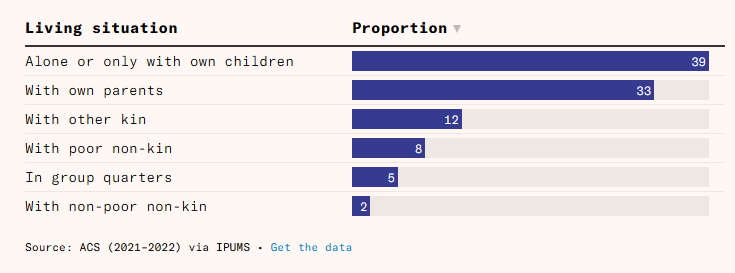

One common anti-urbanist argument is that families simply don’t want to live in cities. But analysis by New York’s Department of City Planning (DCP) also shows that prosperous parts of New York City generally added children, at least in the decade before the rise of the COVID-19 virus. DCP divided the city into “neighborhood tabulation areas” (NTAs) with population ranging from 15,000 to 100,000. DCP’s data showed that the city as a whole lost 2 percent of its under-18 population between 2010 and 2020, but that some areas had significant gains. The biggest gainers were Long Island City (over 200 percent) and four areas where the under-18 population increased by between 50 and 75 percent (the Financial District, Midtown, Midtown South, and Downtown Brooklyn). There seems to be a positive correlation between child growth and housing supply growth, even in these expensive areas. In the Long Island City NTA, the number of housing units increased by over 100 percent between 2010 and 2020- so it is no surprise that the number of children increased. Housing supply increased significantly in three of the four NTAs that added the most children. The number of number of occupied housing units increased by 23 percent in the Midtown South NTA, by 26 percent in the Financial District NTA, and by 86 percent in the Downtown Brooklyn NTA. (Central Midtown was an exception to the rule; housing supply increased more slowly there). By contrast, in Manhattan as a whole, the number of housing units increased by only 7 percent, and the number of children actually declined. Moreover, affluent areas that added very little housing supply tended to gain under-18 residents at a much slower pace. For example, in the three Upper East Side (NTAs) (Lenox Hill, Carnegie Hill, Yorkville) the number of housing units increased […]

Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, revolutionised urban theory. This essay kicks off a series exploring Jacobs’ influential ideas and their potential to address today’s urban challenges and enhance city living. Adam Louis Sebastian Lehodey, the author of this collection of essays, studies philosophy and economics on the dual degree between Columbia University and SciencesPo Paris. Having grown up between London and Paris, he is energised by the questions of urban economics, the role of the metropolis in the global economy, urban governance and cities as spontaneous order. He works as an Applied Research Intern at the Mercatus Center. Since man is a political animal, and an intensely social existence is a necessary condition for his flourishing, then it follows that the city is the best form of spatial organisation. In the city arises a form of synergy, the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, for the remarkable thing about cities is that they tap into the brimming potential of every human being. In nowhere but the city can one find such a variety of human ingenuity, cooperation, culture and ideas. The challenge for cities is that they operate on their own logic. Cities are one of the best illustrations of spontaneous order. The city in history did not emerge as the result of a rational plan; rather, what the city represents is the physical manifestation of millions of individuals making decisions about where to locate their homes, carry out economic transactions, and form intricate social webs. This reality is difficult to reconcile with our modern preference for scientific positivism and rationalism. But for the Polis to flourish, it must be properly understood by the countless planners, reformers, politicians and the larger body of citizens inhabiting the space. Enter Jane […]

The benefit-cost ratio of housing supply subsidies looks terrible. And the state of research is even worse.

In Escaping the Housing Trap, Charles Marohn and Daniel Herriges address the role of zoning in creating the housing crisis. Like some other recent books (most notably by Nolan Gray and Bryan Caplan) this book shows how zoning limits housing supply and thus has led to our current housing crisis. But unlike Gray and Caplan, Marohn and Herriges focus on modest, politically feasible reforms rather than on the benefits of total deregulation. Like other authors, Marohn and Herriges discuss the history of downzoning. For example, in Somerville, Mass., a middle-class suburb of Boston with 80,000 residents, only 22 houses conform to the city’s own zoning code. And in San Francisco, 54 percent of homes are in buildings that could not legally be built today. In Manhattan, 40 percent of buildings are nonconforming. Why? Because zoning has become steadily more restrictive over time, making new housing difficult to build. Where development occurs, it is in a tiny fraction of the region’s neighborhoods- usually, either at the outermost fringe of suburbia or in a few dense urban neighborhoods. For example, in Hennepin County, Minnesota (Minneapolis and its inner suburbs) 75 percent of all housing units built between 2014 and 2019 were in 11 percent of the county’s neighborhoods. In Cuyahoga County, Ohio (Cleveland and its inner suburbs) 75 percent of housing units were built in under 5 percent of the county’s neighborhoods. Marohn and Herriges also critique some anti-housing arguments. For example, one common argument is that only public housing is useful, because the very poor will never be served by the market. They correctly respond that even if there will always be some people in need of government assistance, adequate housing supply will reduce that number. They write that housing policy “will look very different in a situation where the market […]