Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Nolan Gray plunges into the Sam Raimi "Spider-Man" trilogy to uncover the housing problems (and solutions) of expensive cities like New York.

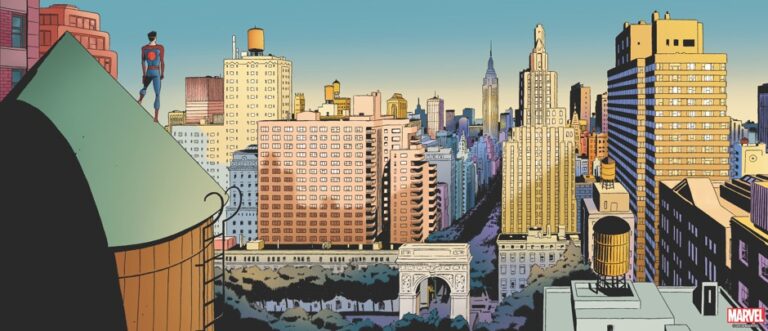

With Spider-Man: Far From Home hitting theaters earlier this month, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has taken one of the series’ biggest risks yet: pulling Spider-Man out of New York City. The gravity of this decision is baked into the film’s title — with good reason. More than any other Marvel superhero, Spider-Man is a uniquely urban superhero. Of course, his iconic powers — web-slinging and wall-crawling — depend on a forest of skyscrapers. But on a deeper level, Parker’s problems are quintessentially urban. Repeatedly, Peter encounters the issue of housing affordability, a recurring challenge for him and Aunt May in the comics and a key issue in the Sam Rami films from 2002 to 2007. In the Rami trilogy, Uncle Ben’s death pushes the family’s already-precarious financial situation into a monetary melee. We witness Aunt May desperately attempt to refinance, though she ultimately faces foreclosure and eviction. Rami’s Spider-Man (2002) stays true to the comics in putting Peter Parker’s family in Forest Hills — a well-heeled Queens neighborhood, depicted in the films as lower-middle class. Their home was assessed this year at approximately $850,000, which would entail a monthly mortgage payment of roughly $3,700 after a hefty downpayment. To make this affordable, Uncle Ben and Aunt May need to somehow make $135,000, a year before property taxes and upkeep. If that’s a stretch for a professional electrician, it’s impossible for a retired homemaker. The frustrations surrounding Aunt May’s eviction are an important part of Parker’s decision to give up being Spider-Man in the second film, and it’s easy to see why: May’s options post-eviction aren’t pretty. Assuming a standard Social Security check and a payout from Uncle Ben’s death, Aunt May really only has about $1,000 to spend on rent. Rising rents will make it tough to find a decent […]

Here’s something I hadn’t thought of in quite this way (but many others probably have): In a living city, space is cheap enough so that people with wacky (often “terrible”) new ideas can test them out, while wealthier people in that city search for wacky new things to try out (because they’ve experienced a lot of other things). In “creative” markets, such as for art, the demand side complements the supply side across income groups in an interesting way.

The starting point for Jacobs’s analysis and the focus of much of her thought is the city, its nature and significance. There are plenty of books out there that in some way celebrate cities. Many describe cities as engines of economic development, wellsprings of art and culture, and incubators of ideas religious, social, and scientific. But few go very far in explaining why and how all that usually happens in a city. Fewer still view the urban processes as expressions of “emergence,” or what some social theorists describe using the related term “spontaneous order.” That is the perspective of this book and its main contribution: To look closely at what makes a city a spontaneous order and an engine of innovation, and to trace the analytical and policy consequences of viewing it this way. Jane Jacobs is one of those exceptions, indeed an outstanding one. In fact, she is probably the first to carefully examine, not only the nature and significance of cities, but to distill realistic principles that govern urban systems and to analyze the mechanisms of economic change that follow from those principles. Her analysis of the relation between the design of public space and social interaction offer insights that complement, and often exceed, those of Max Weber, Henri Pirenne, Georg Simmel (pdf), Kevin Lynch, and others. Her work also has deep connections with modern social theorists such as F.A. Hayek, Elinor Ostrom, Mark Granovetter, and Geoffrey West. But she was not the first to develop conceptual tools congenial to understanding urban processes as emergent, spontaneous orders. In fact they have largely been available for decades in the field of economics, although few professional economists, including urban economists, have fully appreciated the urban origins of many of their standard concepts and tools of analysis. Indeed, there is a […]

Spoiler Warning: This post contains minor spoilers about Season Two of Parks and Recreation, which aired nearly 10 years ago. Why have you still not watched it? Lately I have been rewatching Parks and Recreation, motivated in part by the shocking discovery that my girlfriend never made it past the first season. The show is perhaps the most sympathetic cultural representation of local public sector work ever produced in the United States. The show manages to balance an awareness of popular discontent with “government” in the abstract— explored through a myriad of ridiculous situations—with the more mild reality that most local government employees are well-meaning, normal, mostly harmless people who care about their communities. This makes the character of Mark Brendanawicz, Pawnee’s jaded planner, all the more interesting. It’s conspicuous that even in a show so sympathetic to local government, the city planner remains a cynical, somewhat unlikable character. Unlike Ron Swanson, Brendanawicz at one point meant well and has no ideological issues with government; he regularly suggests that he was once a true believer in his work, if only for “two months.” Yet unlike Leslie Knope, he didn’t choose government. In his efforts to win back Anne, Andy chides Brendanawicz as a “failed architect,” an insult which seems to stick. Brendanawicz ultimately leaves the show as an unredeemed loser: after taming his apparent self-absorption and promiscuity, he prepares to propose to Anne, only to have her preemptively break up with him. When the government shutdown occurs at the end of Season Two, Brendanawicz takes a buyout offer, and resolves to go into private-sector construction. Leslie, who had once adored him, dubs him “Brendanaquits,” and we never hear from Pawnee’s city planner again. It isn’t hard to see why Brendanawicz was unceremoniously scrapped: he was ultimately a call-back to the harsher world […]

There are many ways to tell the story of urban-policy failure. Economists have shown how rent control creates housing shortages, sociologists how welfare programs destroy poor communities, and urbanologists how urban planning can debilitate cities. In his book The Future Once Happened Here, historian Fred Siegel has added a new and insightful chronicle of modern liberalism’s influence on social policy in New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles over the last 30 years. Siegel identifies racial tension as a main force that has driven urban policy since the 1960s. He lucidly and engagingly describes how that policy, informed by “riot ideology” based on liberal guilt and fear, transformed some major American cities from communities of tolerant strangers and great incubators of ethnic integration into rolling riots and sinkholes of federal largess. Associated with the riot ideology is what Siegel terms “dependent individualism,” the idea that each person has an absolute right to his “lifestyle,” at public expense and regardless of the consequences for social cooperation. Those consequences have been a “moral deregulation of public space,” which has eroded the trust that urbanologist Jane Jacobs identified as the lubricant that permits great cities to work well. The largest part of the book is devoted to New York City. Siegel explains how Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s success in getting federal aid from FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s set the pattern for fiscal irresponsibility in New York for the next five decades. Consequently, New York became dependent on an artificial, make-work economy, based on federally funded jobs and welfare bolstered by dependent individualism and the riot ideology. Nevertheless, its productive sector was still so large that both New York City and the state of New York have regularly sent more taxes to Washington than they have received in transfers. Surprisingly, supporters of […]

“Everything passes. Nobody gets anything for keeps. And that’s how we’ve got to live.” –Haruki Murakami I feel lucky to live in Brooklyn Heights. It’s been called New York City’s first suburb. It offers easy access to most parts of Manhattan, thanks to the convergence of several important subway lines, and the view of Lower Manhattan from here is one of the most spectacular in the City. Not surprisingly it’s one of the most desirable and expensive neighborhoods to live in. Along its periphery, warehouses and office buildings are constantly being converted into residences, to go along with townhouses in the neighborhood proper that were built in the early 1800s, as developers try to keep up with a demand that has remained strong even in a slack housing market. In my opinion the Brooklyn Heights district is one of the most charming, and probably the prettiest, in all of New York. So what’s to complain about? Urban Renewal and Landmarks Preservation Three things. First, in 1939 the area just east of the neighborhood underwent the largest urban renewal project of its time, razing 125 buildings over 21 acres and creating “Cadman Plaza,” the first of many so-called “super-blocks” built in major cities across the United States in the mid-twentieth century. Later, between 1947 and 1954, local authorities constructed the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) along the northern and western borders. Then in 1965 Mayor Wagner signed a law that made Brooklyn Heights the City’s first historic district (there are currently 100 such districts in New York) and eventually gave rise to the important Landmarks Preservation Commission. Cadman Plaza and the BQE effectively cut the Heights off from the hurly-burly of commercial development in neighboring districts. The Landmarks Preservation Commission has made it very hard and very costly to change the existing […]

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities is a short, often wonderful but consistently enigmatic (at least to me) novel about an extended conversation between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan. Marco tells the Khan a series of tales about fantastical cities he’s perhaps only imagined. I’ve always assumed that the book’s title refers to that imaginary quality, since no one besides Marco himself has actually seen the cities he describes, and they likely exist only in his mind or in the words as he utters them. Recently, I hosted a couple of group “tours” of my neighborhood. These tours are called “Jane’s Walks” in memory of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs. In the course of explaining her (mostly laissez-faire) principles to the group, I realized there’s another interpretation of Calvino’s title that I much prefer. It is this: A city—especially a great one—cannot really be seen. Paradoxically, the closest we can come to actually seeing one is through the imagination. Otherwise, it’s invisible. Moreover, if you can fully comprehend a place, then it’s not a city. You Don’t See a City on a Map If you think about a particular city that you know, what comes to mind? An image, a feeling, a smell, or a sound? Before we visit a city, we may look at pictures of parts of it, perhaps its famous landmarks, but these mean little to us in themselves. We may study a map of Paris to get a sense of the layout or the general shape of the metropolis. But what we are seeing is not the city of Paris but something highly abstract, abstracted not only from Paris but also from the particular reality of our lives. If, before going there, we could somehow look at a photo we will take of Paris, the scene would not evoke much from us […]

In my last article, I wrote about how an economically and culturally vital city is able, without central planning, to generate two things that are essential to the city’s success: diversity and cohesion. I argued that when lots of people who reflect a huge range of skills and tastes can live together peacefully (diversity) and when they feel free to associate to any degree they choose (cohesion), the result tends to be rich, complex, and dynamic social networks that channel information from person to person rapidly and effectively. For many who hear this argument, however, how this happens remains a mystery. And I don’t blame them for feeling that way. Some urban economists and urban sociologists explain this in terms of “knowledge spillovers.” Proximity enables people who are socially distant to mingle and exchange ideas; the image of chance meetings and chatting up over coffee or a beer comes to mind. Sometimes it does happen that way. Many of the innovators in Silicon Valley in the 1960s, for example, informally traded ideas at the famed Wagon Wheel bar. The term “spillover” evokes this informality over the occasional sloshed mug of beer (or sloshed patron). Social Media: Complement or Substitute? I listened to an interview recently with urban economist Edward Glaeser of Harvard University on Russ Roberts’ podcast, Econtalk. The main topic was the recent declaration of bankruptcy by the Detroit city government, but the discussion also touched on more basic issues such as why people still need to live in cities. Some of my colleagues argue, for example, that face-to-face interactions are becoming obsolete with technical advances such as Facebook, Skype, and email. Back in the early twentieth century, as the telephone spread to more and more homes, pundits at the time—among them the architect Frank Lloyd Wright—claimed that science would “obliterate distance” […]