Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

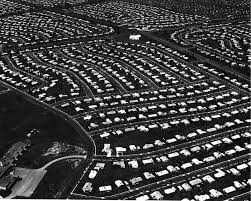

The economist F.A. Hayek explained why it’s impossible for human reason to successfully design complex systems such as markets or language. One can’t simply say, “Hey, I’d like to invent a Germanic language that does away with those troublesome genders and inflections but has plenty of Latin- and Greek-based words sprinkled in.” That would be English, of course, which evolved over centuries of trial and error. (Some might want to use Esperanto as a counterexample, but let’s face it: There are probably more people today who can speak Latin, a dead language, than can speak Esperanto.) The current fashion to construct mass-transit infrastructure in places, such as Phoenix, where none had existed before is like this in a certain sense. As Hayek explained, the problem is that reason, while powerful and creative, is imperfect and extremely limited compared to the complexity and open-endedness of the social world. As a result, all actions will have unintended consequences. The trick is to find “rules of the game” – such as private property and norms of reciprocity – that over time generate consequences that correct errors and promote rather than prevent social cooperation. While economists and social theorists since Adam Smith have understood this, many in the urban-planning profession don’t seem to have fully grasped the message. When Sprawl Was Good Since at least the 1970s in the United States the idea has been to try as much as possible to substitute mass-transit for the private car. To New Urbanists, for example, that is the key to solving a host of social ills including pollution, overcrowding, racial discrimination, oil-dependency, and alienation – all allegedly connected to the phenomenon of “sprawl.” (See, for example, the Charter of the New Urbanism.) I’ve been rereading Robert Bruegmann’s excellent book, Sprawl: A Compact History, in which he […]

Sometimes, prosperity is an illusion. The massive building boom in the People’s Republic of China is creating outer signs of affluence, but there isn’t enough demand to put residents in the new homes. As in many similar urban projects across the country, the Chinese government has been pouring billions of dollars into Gansu Province to build a new city called Lanzhou New Area. The Washington Post reports, This city is supposed to be the “diamond” on China’s Silk Road Economic Belt — a new metropolis carved out of the mountains in the country’s arid northwest. But it is shaping up to be fool’s gold, a ghost city in the making. Lanzhou New Area, in Gansu province, embodies China’s twin dreams of catapulting its poorer western regions into the economic mainstream through an orgy of infrastructure spending and cementing its place at the heart of Asia through a revival of the ancient Silk Road. Hundreds of hills on the dry, sandy Loess Plateau were flattened by bulldozers to create the 315-square-mile city. But today, cranes stand idle in planned industrial parks while newly built residential blocks loom empty. Streets are mostly deserted. Life-size replicas of the Parthenon and the Sphinx sit surrounded by wasteland, monuments to profligacy. Spontaneous Cities China’s central planners haven’t even begun to appreciate, let alone practice, the lessons of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs, who viewed cities and the socioeconomic processes that go on in them as largely the result of spontaneous, unplanned entrepreneurial development. As an economist quoted in the Washington Post article points out, Urbanization and modernization are processes that naturally take place.… You can’t force it to happen or have 1,000 places copy the same model. Construction of these so-called ghost cities is likely financed by artificial credit expansion. In other words, people […]

Urban Institute Press • 2005 • 494 pages • $32.50 paperback In Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government, Robert H. Nelson effectively frames the discussion of what minimal government might look like in terms of personal choices based on local knowledge. He looks at the issue from the ground up rather than the top down. Nelson argues that while all levels of American government have been expanding since World War II, people have responded with a spontaneous and massive movement toward local governance. This has taken two main forms. The first is what he calls the “privatization of municipal zoning,” in which city zoning boards grant changes or exemptions to developers in exchange for cash payments or infrastructure improvements. “Zoning has steadily evolved in practice toward a collective private property right. Many municipalities now make zoning a saleable item by imposing large fees for approving zoning changes,” Nelson writes. In one sense, of course, this is simply developers openly buying back property rights that government had previously taken from the free market, and “privatization” may be the wrong word for it. For Nelson, however, it is superior to rigid land-use controls that would prevent investors from using property in the most productive way. Following Ronald Coase, Nelson evidently believes it is more important that a tradable property right exists than who owns it initially. The second spontaneous force toward local governance has been the expansion of private neighborhood associations and the like. According to the author, “By 2004, 18 percent—about 52 million Americans—lived in housing within a homeowner’s association, a condominium, or a cooperative, and very often these private communities were of neighborhood size.” Nelson views both as positive developments on the whole. They are, he argues, a manifestation of a growing disenchantment with the “scientific management” of […]

In The Road to Serfdom, F. A. Hayek tells us that intellectuals and governments in the twentieth century tragically abandoned the road to liberty in pursuit of collectivist utopias. That road stretched at least as far back as the democratic polis of ancient Greece, but it was not always straight and unbroken. Once, it was completely lost, only to be rediscovered centuries later. The idea of liberty emerged in the struggle between the forces of collectivism and individualism. It is the idea that each of us has a rightful sphere of autonomy in which we may be free from aggression. In politics this manifested itself as liberal democracy, in economics as market competition, and in the broader social realm as scientific advance, artistic expression, and religious tolerance. In his concise masterpiece, Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade, the Belgian historian Henri Pirenne explains just how, long after the fall of the western Roman empire, the liberal idea gradually reemerged and how this was directly tied to the birth of the modern city. The Decline of Cities and Civilization Between AD 400 and 900 cities virtually disappeared from Europe. Even in Rome, which at its height had a population of one million, the population fell to mere thousands – most of whom were either Churchmen or those who served them. Bishops and clerics dominated urban life, while princes, who had little reason to spend time in dreary medieval towns, focused attention on protecting their feudal estates, earning tribute from their vassals, and exploiting the labor of their serfs. Then as now, nobles followed wealth, and in the Middle Ages, as trade among cities dwindled, the basis for wealth went from money to land. Money, liquid and essential for commerce, became superfluous, while control and acquisition of land became […]

The University of Chicago Press has published a “definitive” edition of F. A. Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty under the editorial guidance of long-time Hayek scholar Ronald Hamowy. Given my interest in urban issues, it’s a good time for me to focus on chapter 22, “Housing and Town Planning.” It has several insights that I really like, but given the constraints of this column, for now I’ll talk about Hayek’s take on rent control. I must confess that it was several years after I became interested in the nature and significance of cities that I learned that Hayek had written anything on what we in the United States call “urban planning.” (Well, that’s not quite true; I did read The Constitution of Liberty as a graduate student, but in those days I didn’t appreciate how important cities are to both economic and intellectual development, so it evidently made no impression on me.) The analysis has a characteristically “Hayekian” flavor to it, by which I mean he goes beyond purely economic analysis and points out the psychological and sociological impact of certain urban policies that reinforce the dynamics of interventionism. The Economics of Rent Control Hayek’s economic analysis of rent control sounds familiar to modern students of political economy perhaps because it’s so widely (though not universally) accepted. This was hardly the case in 1960, when his book was first published. Hayek points out that despite the good intentions of those who support it, “any fixing of rents below the market price inevitably perpetuates the housing shortage.” That’s because at the artificially low rents the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. One effect of the chronic housing shortage that rent control produces is a drop in the rate at which apartments and flats would normally turn over. Instead, rent-controlled housing becomes […]

“Everything passes. Nobody gets anything for keeps. And that’s how we’ve got to live.” –Haruki Murakami I feel lucky to live in Brooklyn Heights. It’s been called New York City’s first suburb. It offers easy access to most parts of Manhattan, thanks to the convergence of several important subway lines, and the view of Lower Manhattan from here is one of the most spectacular in the City. Not surprisingly it’s one of the most desirable and expensive neighborhoods to live in. Along its periphery, warehouses and office buildings are constantly being converted into residences, to go along with townhouses in the neighborhood proper that were built in the early 1800s, as developers try to keep up with a demand that has remained strong even in a slack housing market. In my opinion the Brooklyn Heights district is one of the most charming, and probably the prettiest, in all of New York. So what’s to complain about? Urban Renewal and Landmarks Preservation Three things. First, in 1939 the area just east of the neighborhood underwent the largest urban renewal project of its time, razing 125 buildings over 21 acres and creating “Cadman Plaza,” the first of many so-called “super-blocks” built in major cities across the United States in the mid-twentieth century. Later, between 1947 and 1954, local authorities constructed the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) along the northern and western borders. Then in 1965 Mayor Wagner signed a law that made Brooklyn Heights the City’s first historic district (there are currently 100 such districts in New York) and eventually gave rise to the important Landmarks Preservation Commission. Cadman Plaza and the BQE effectively cut the Heights off from the hurly-burly of commercial development in neighboring districts. The Landmarks Preservation Commission has made it very hard and very costly to change the existing […]

Jane Jacobs (May 4, 1916 – April 25, 2006), one of the most important and influential public intellectuals of the twentieth century, died a few days shy of her ninetieth birthday. The intellectual legacy she left for social theorists is as significant as that of anyone else of her generation. She was the author of nine books, including The Economy of Cities (1969), Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1984), The Nature of Economies (2000), and her most famous work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). She also published an article in the prestigious American Economic Review (“Strategies for Helping Cities,” September 1969). Most are surprised to learn that she held only a high-school diploma and began her book-writing well past the age of 40. In her first book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs argued that the urban planners of her day, infected by the top-down collectivist ideology that was the conventional wisdom among nearly all intellectuals, ignored the perspective of ordinary people on the street. Her position, radical for its time, was that real cities don’t conform to one person’s or group’s aesthetic ideal because visual order is not the same as actual social order. She argued that complex social orders, such as a city, begin with ordinary people forming informal relations with one another in the neighborhoods in which they live, play, or work. Such networks emerge and thrive when people are able to have free and casual contact with acquaintances and strangers alike in the safety of streets, sidewalks, and other public spaces. But most of that safety is achieved not by aggressive formal policing but by voluntary recognition and informal enforcement of local norms. The key is for each neighborhood or city district to have sufficiently diverse attractions at […]

Every so often during his tenure as mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg tried to push through congestion pricing, in which drivers would have to pay to use city streets in Midtown and Lower Manhattan. That’s a popular solution to chronic overcrowding but, like drinking coffee to try to cure a hang over, it doesn’t really get to the heart of the matter. More intervention usually doesn’t solve the problems that were themselves the result of a prior intervention. Let me explain. In 2011, I had the opportunity to participate in an online discussion over at Cato Unbound. It focused on Donald Shoup’s book The High Cost of Free Parking, which looks at the consequences of not charging for curbside parking. If you’ve ever tried to find a parking spot on the street in a big city, especially on weekdays, you know how irritating and time-consuming it can be. It may not top your list of major social problems, except perhaps when you’re actually trying to do it. In fact, according to Shoup about 30 percent of all cars in congested traffic are just looking for a place to park. The problem though is not so much that there are too many cars, but that street parking is “free.” Except, of course, it isn’t free. What people mean when they say that some scarce commodity is free is that it’s priced at zero. Some cities, such as London, Mayor Bloomberg’s inspiration, charge for entering certain zones during business hours — with some success. (As well as unintended consequences: People living in priced zones pay much less for parking and higher demand has driven central London’s real-estate prices, already sky high, even higher). But this doesn’t really address what may be the main source of the problem: the price doesn’t […]

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities is a short, often wonderful but consistently enigmatic (at least to me) novel about an extended conversation between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan. Marco tells the Khan a series of tales about fantastical cities he’s perhaps only imagined. I’ve always assumed that the book’s title refers to that imaginary quality, since no one besides Marco himself has actually seen the cities he describes, and they likely exist only in his mind or in the words as he utters them. Recently, I hosted a couple of group “tours” of my neighborhood. These tours are called “Jane’s Walks” in memory of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs. In the course of explaining her (mostly laissez-faire) principles to the group, I realized there’s another interpretation of Calvino’s title that I much prefer. It is this: A city—especially a great one—cannot really be seen. Paradoxically, the closest we can come to actually seeing one is through the imagination. Otherwise, it’s invisible. Moreover, if you can fully comprehend a place, then it’s not a city. You Don’t See a City on a Map If you think about a particular city that you know, what comes to mind? An image, a feeling, a smell, or a sound? Before we visit a city, we may look at pictures of parts of it, perhaps its famous landmarks, but these mean little to us in themselves. We may study a map of Paris to get a sense of the layout or the general shape of the metropolis. But what we are seeing is not the city of Paris but something highly abstract, abstracted not only from Paris but also from the particular reality of our lives. If, before going there, we could somehow look at a photo we will take of Paris, the scene would not evoke much from us […]

Why are a growing number of libertarians fascinated by cities and indeed pinning their hopes for a freer future on cities? Two examples of this just from recent Freeman issues are by Zachary Caceres on startup cities and the winner of the Thorpe-Freeman Blog Contest, Adam Millsap, responding to one of the articles in an entire cities-themed issue. There is a deep affinity between cities and markets, and indeed between cities and liberty. (As the old saying goes, “City air makes you free.”) Cities aren’t merely convenient locations for markets; a living city (which I’ll define in a moment) is a market, and the first cities probably originated as markets. Much has been written on this connection, but I’d like to point out another link between cities and markets—one that comes from the great 20th century urbanist, Jane Jacobs. Consciously or not, Jacobs followed the tradition of the influential German sociologist Max Weber in seeing cities as essentially markets. Indeed, in her 1969 book The Economy of Cities, she defined a city, or what I like to call a “living city,” as “a settlement that consistently generates its economic growth from its own local economy.” Moreover, I’ve written elsewhere that today’s economic phenomena of demand, supply, the price system, markets, externalities, public goods, and division of labor had their genesis in an urban setting. The fundamental (classical) liberal concepts of property rights, economic freedom, and the rule of law did not develop among wandering nomads, farmers, or in small villages but perforce from the interactions of strangers with diverse cultures and backgrounds interacting in dense proximity with one another. Diversity… In her great book of 1961, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs first presented her argument that the key feature of any great city is its diversity. […]