Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

As foreigners, we are mesmerized by zakkyo buildings or yokocho, but within Japan, scholars, and authorities often ignore and neglect them as urban subproducts. In spite of their conspicuous presence and popularity, the official discourse still considers most of Emergent Tokyo as unsightly, dangerous, or underdeveloped. The book offers the Japanese readership a fresh view of their own everyday life environment as a valuable social, spatial, and even aesthetic legacy from which they could envision alternative futures.

American YIMBYs point to Tokyo as proof that nationalized zoning and a laissez faire building culture can protect affordability. But a great deal of that knowledge can be traced back to a classic 2014 Urban Kchoze blog post. As the YIMBY movement matures, it's time to go books deep into the fascinating details of Japan's land use institutions.

Are there diverse places in the U.S. where racial differences among residents are small enough to be undetectable to a typical resident? Places where Roger Starr's ideal of "integration without tears" might be a reality, where people of different races socialize as equals, share culture and priorities, and work in the same range of occupations?

Urbanist and YIMBY Twitter had a field day dunking on Nathan J. Robinson, whose essay in his publication Current Affairs called for building new cities in California. But California really could use some new cities - and we need to think about them in primarily economic terms.

A trip to Houston reveals how a city can design without shame, urbanize around cars, and achieve privacy in a context of radical integration.

The narrow choice of city versus suburb is a balance of cost and amenities. But the bigger question – in which region should I make my home? – requires one to look on a higher plane.

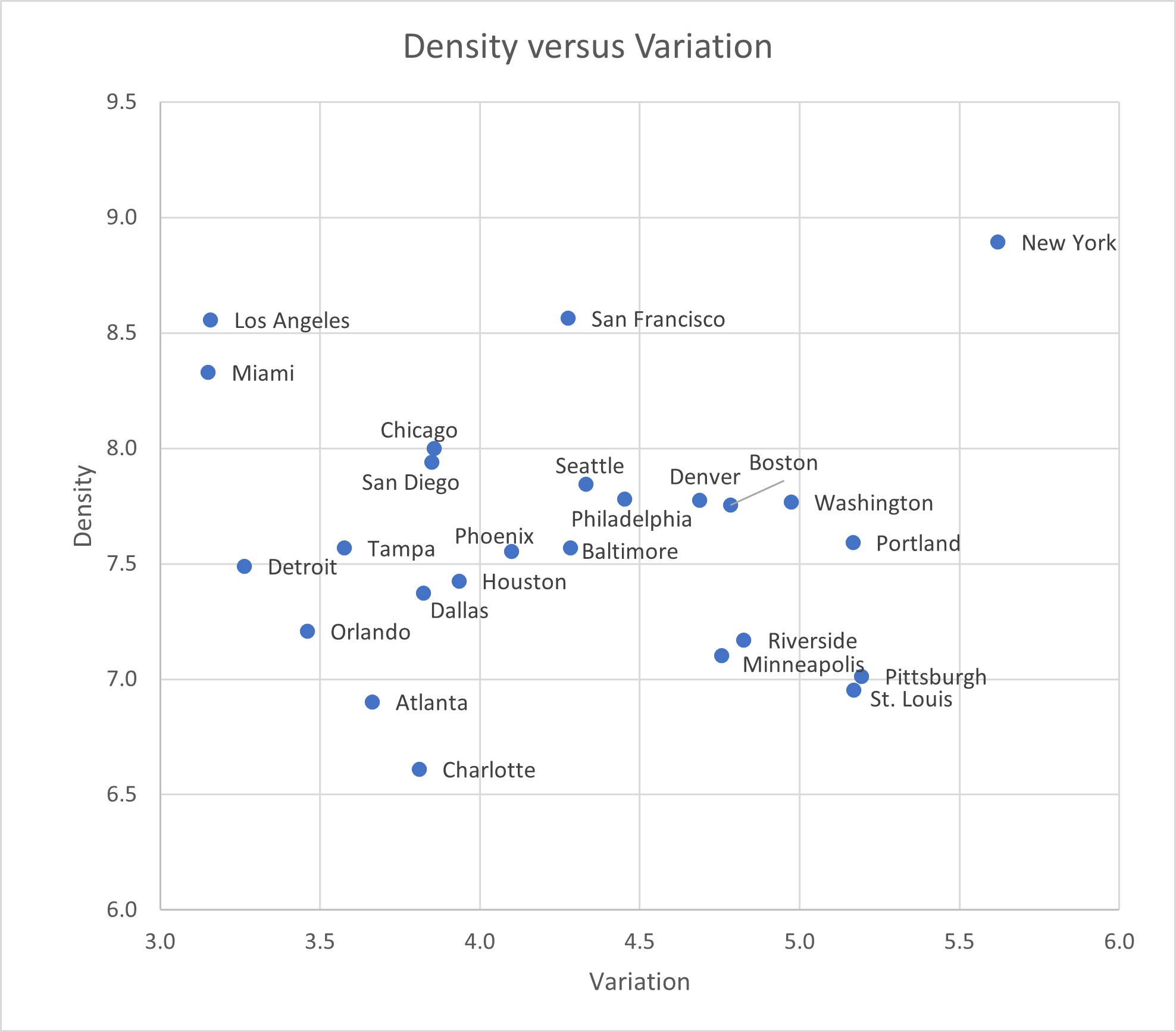

A quick data exercise shows that LA really is unique among big American metros, matched only by its East Coast twin, Miami.

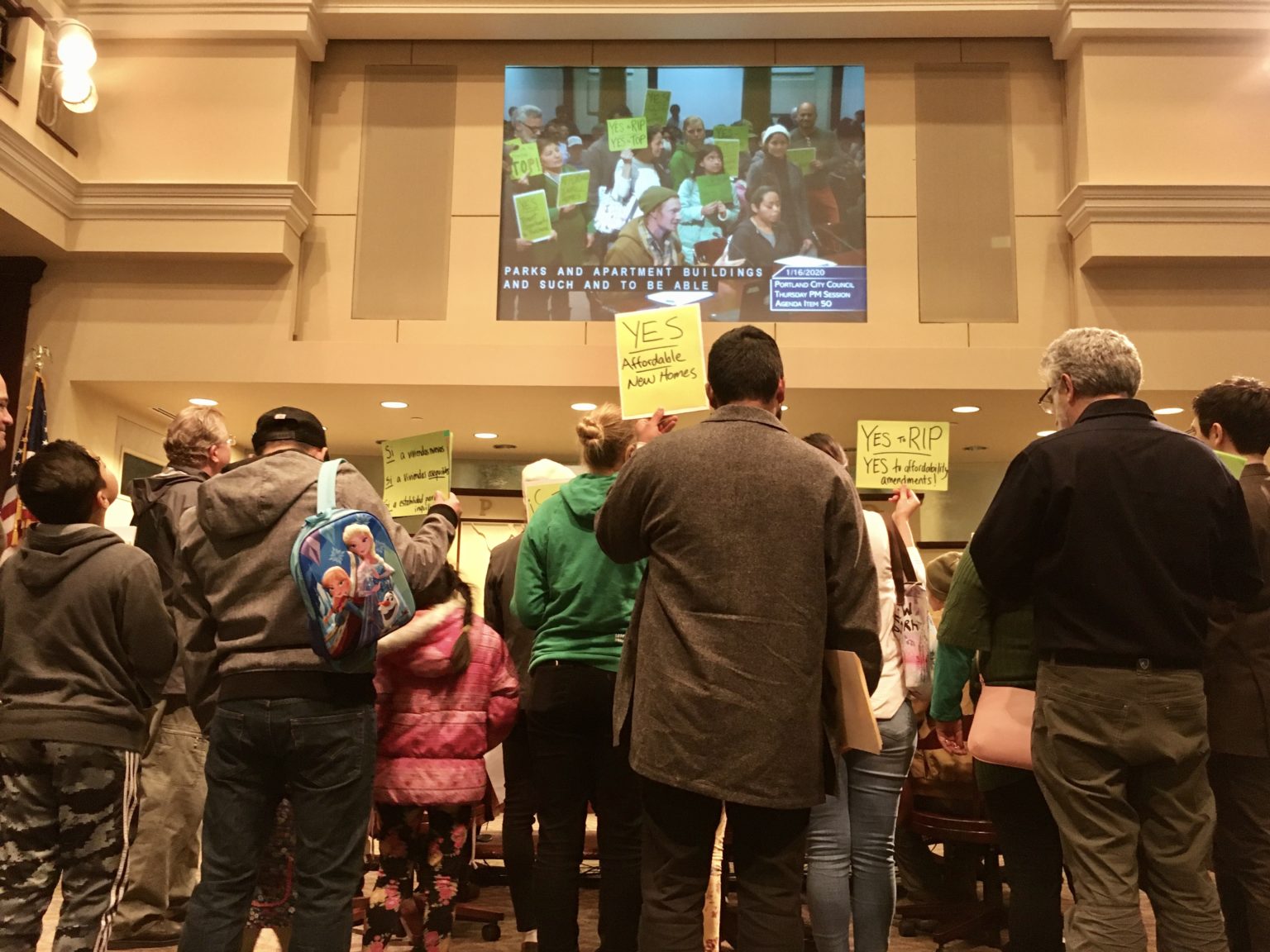

Case studies from several authors help explain the gritty politics of "Yes." The list includes three classics and will be expanded with reader submissions.

In July, I showed that an otherwise careful group of researchers at the Othering and Belonging Institute were using a measure of statistical racial segregation that confounds diversity with segregation. Briefly, regions with more variety in the racial makeup of their neighborhoods will show up as statistically “segregated.” Regions where all neighborhoods are pretty similar will show up as statistically “integrated.” To their credit, the study authors corresponded with me at length and adjusted their Technical Appendix to emphasize limitations that I had pointed out. Today, Mark Zandi, Dante DeAntonio, Kwame Donaldson, and Matt Colyar of Moody’s Analytics released a much less careful study purporting to show the “macroeconomic benefits of racial integration.” But if one were to make the mistake of taking their study at all seriously it would lead one to the opposite conclusion: mostly-white counties do better economically. They discovered white privilege and mislabeled it “integration.” (When economists talk about “segregation” statistically, they mean differences in racial proportions across neighborhoods. This is not the same as the de jure segregation regime imposed in the American South. It’s not even the de facto segregation that persists in some neighborhoods today.) The easiest way to see Zandi et al’s mistake is to work backwards from the table of county results they (helpfully) published. The most integrated county in America, in their analysis, is Kennebec County, Maine. It’s 94.6% white. The rest of the most-integrated counties are similarly pallid – with the exception of Webb County, Texas, which is 95% Hispanic. In each of these counties, integration is a mathematical product of the lack of diversity. With hardly any minorities, hardly any neighborhood can diverge from the dominant group. These extreme counties aren’t an accident. Whereas most researchers treat metropolitan areas together, Zandi’s team worked with counties. Several of their […]

Hayek says that planning is the road to serfdom. Holland may be the most thoroughly planned country on earth - and it's delightful. How does a market urbanist respond to excellent planning?