Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Why are Max Holleran's book, Richard Schragger's law review article, and randos on Twitter all misinterpreting one important research article?

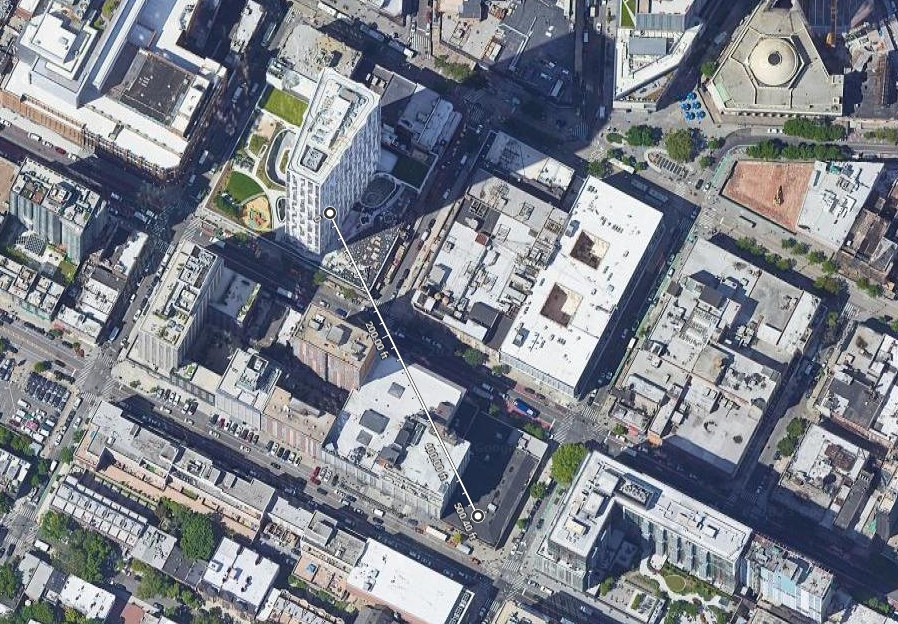

For a reading group, I recently read two papers about the costs and (in)efficiencies around land assembly. One advocated nudging small landowners into land assembly; the other is an implicit caution against doing so. Graduated Density Zoning Although he’s mostly known for parking research and policy, Donald Shoup responded to the ugliness of eminent domain in Kelo v. City of New London, with a 2008 paper suggesting “graduated density zoning” as a milder alternative. Graduated density zoning would allow greater densities or higher height limits for larger parcels – so that holdouts would face greater risk. Samurai to Skyscrapers Junichi Yamasaki, Kentaro Nakajima, and Kensuke Teshima’s paper, From Samurai to Skyscrapers: How Transaction Costs Shape Tokyo, is a fascinating and technical account of how sweeping changes put the relative prices of different-sized lots on a roller-coaster from the 19th century to the present. First, large estates were mandated as a way for the shogun to keep nobles under his close control. Then, with the Meiji Restoration, the nobles were released to sell their land, swamping the market and depressing prices. The value of land in former estate areas stayed low into the 1950s. But with the advent of skyscrapers – which need large base areas – the old estate areas first matched and then exceeded neighboring small-lot areas in central Tokyo. A meta-lesson from this reversal is that “efficiency” is a time-bound concept. One can imagine a 1931 urban planner imposing a tight street grid and forcing lot subdivision to unlock value on the depressed side of the tracks. That didn’t happen; instead, the large lots were a land bank that allowed a skyscraper boom right near the heart of a very old city, helping propel the Japanese economy beyond middle-income status. We should take a long, uncertain view of […]

Market Urbanism is proud to welcome Szymon Pifczyk as a new writer. Here's a short interview we conducted over email.

Urbanists and zoning reformers would really like estimates that tell us how changing the built environment will change our own habits. But many of the variables that inform Jones' estimates won't change with environment: age, race, income, education. The fault is not in our stars, but in ourselves.

Ever wondered how you could make your urbanism hobby a full-time job? Come work with me & Emily Hamilton at the Mercatus Center’s Urbanity project: Are you a gritty, liberty-minded researcher who is passionate about cities? This is a unique opportunity for an aspiring scholar to develop a portfolio of research in urban economics, planning, housing affordability, and land use regulations with talented scholars and staff at the world’s premier university source for market-oriented ideas. The ideal candidate will think like an economist, deftly handle complex datasets, and express himself or herself clearly in writing. This position reports to the program manager of the Urbanity Project. Responsibilities Include:•Collaborate with research fellows on quantitative research projects using GIS and data analysis software.•Read, understand and summarize scholarship in urban economics, planning, and land use law.•Translate and promote research through media and outreach engagement.•Support Mercatus scholars and affiliated fellows in consultations with city and state policymakers. Requirements Include:•Degree or equivalent knowledge in economics, urban & regional planning, or a related field•Experience with either a GIS or a statistical software package such as Stata and R; familiarity with and willingness to master the other•Strong verbal, written, and interpersonal communication skills •Enthusiasm for collaboration and adaptability to a varying mix of responsibilities•A strong interest in the Mercatus Center’s mission, with a specific focus on cities and liberty https://us63.dayforcehcm.com/CandidatePortal/en-US/mercatus/Posting/View/732

What's the best urban path in America? Vote on Twitter this month for nominees in the Urban Paths World Cup.

In a tweet this week, the Welcoming Neighbors Network recommended that pro-housing advocates keep supply-and-demand arguments in their back pockets and emphasize simpler housing composition arguments: This advice makes an economist’s mind race. We know, after all, that supply and demand work. But we’re not so sure about composition changes. If “affordability” is achieved by building units that people don’t want (in bad locations, too small, lacking valued attributes), then the price-per-unit can be low without actually benefiting people on their own terms. Even if existing homes are bigger than many people want, at least some of the price decline from building smaller homes is the “you get what you pay for” effect. (Incidentally, this is the opposite concern from that held by econ-skeptics concerned about gentrification: they worry that new housing will be too good or that investment will upscale neighborhoods. This inverts the trope that economists “only care about money”.) A few days later, a Maryland state senator asked me that very supply-and-demand question: “What’s the evidence that large-scale upzoning leads to affordability?” This is a tough question. First, large-scale upzonings are very scarce. Second, even if one occurs, it’s not in an experimental vacuum. Three kinds of affordability Let’s specify that an upzoning likely promotes affordability in three ways: Supply and demand You get what you pay for Only pay for what you want The first channel is obvious – it explains why Cleveland is cheaper than Boston. The second source of affordability is valuable for people at risk of homelessness, but doesn’t make most people better off. The third source – what WNN recommends advocates emphasize – is that many regulations require people to pay for more housing (or pricey attributes) that they don’t want. In a lot of cases, the last two effects will go […]

In an encouraging post this morning, Matt Yglesias – one of the O.G. YIMBYs – summed up 10 years of success since his book, The Rent Is Too Damn High, was published. If you’d asked me, I’d have guessed that Too Damn High was published in 2015 or 2016, when YIMBY was in its infancy and researchers like me were starting to nose around zoning as a major regulatory cost. Yglesias was several years ahead of the curve. In his post, Yglesias gives free marketers a lot of credit for being for upzoning before it was cool. Market urbanists will certainly accept the compliment, and the legacies of Bernard Siegan and Bob Ellickson (1972…2022 – incredible!) are undeniable. But there’s another major part of the pre-YIMBY world that’s missing in this story, which is the progressive critics of suburban zoning. One of the graphs that keeps me up at night is the Google n-gram showing that “exclusionary zoning” was less a part of the discourse in the 2010s than it was throughout the 70s and 80s… and yet the activists of the time accomplished so little! The progressive critics of zoning, such as Paul Davidoff and Myron Orfield, were focused on allowing multifamily housing – especially if subsidized – in the suburbs. Urban housing markets were pretty slack at the time, and adding affordable housing in central cities risked concentrating poverty. A great book that covers a specific housing battle spanning the 1990s is Lawrence Lanahan’s The Lines Between Us. Alongside YIMBY As I understand it, these activists’ energy became formalized in the affordable housing industry. A lot of those institutions – and individuals – are still active. They have a mixed relationship with the YIMBY movement. In some cities and states, they’re enthusiastic participants. In others, they’re antagonistic. It […]

Rent control has devalued property so badly that you could make a million dollars by tearing down a nice 12-unit building in my neighborhood.

Two new estimates of the national housing shortfall offer a seeming contradiction. But we can synthesize the demand and supply models to get close to the truth: High-priced places should build much more housing than Up For Growth estimates and moderate-priced places will build much less housing than the JEC predicts.