Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

How do urbanists respond to a disaster? Emails from Brazil's Rodrigo Rocha show innovation and personal resilience in the face of crisis.

Check out my new post at Metropolitan Abundance Project: How “inclusionary” are market-rate rentals? In metropolitan Baltimore, a family of four making $73,000 in 2024 qualifies for 60% AMI affordable housing, where it would pay $1,825 per month for rent, utilities included. A third of new market-rate three-bedroom units in Baltimore are rented at around that level.Baltimore is typical, as it turns out. In most U.S. metro areas, a substantial share of rentals constructed since 2010 were, in 2021 and 2022, affordable at 60% of AMI… You can also check out maps showing rentals affordable at 80% and 120% of AMI. The ACS data don’t let me distinguish market-rate from subsidized rentals, so these include LIHTC and other subsidized rentals. Those, however, can’t explain away the core result, and the data don’t show the bifurcated market that some people imagine, with a huge gap between market and deed-restricted rents.

Research shows that the implementation of an eviction moratorium significantly disadvantaged African Americans in the housing search process.

Just 1 in 25 new apartments is owner-occupied. What happened to building condos?

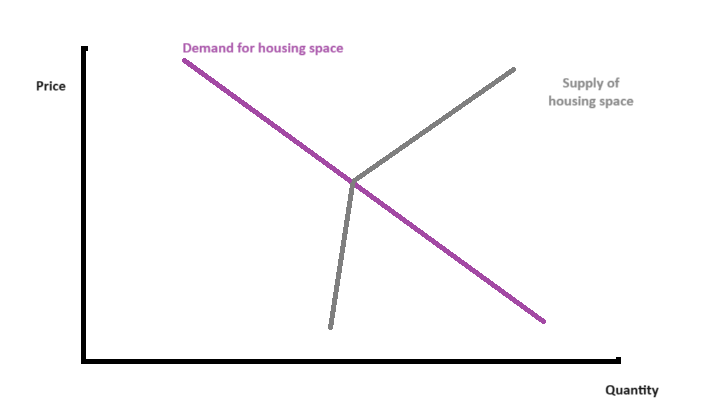

Should YIMBYs support or oppose greenfield growth? Two basic values animate most YIMBYs: housing affordability and urbanism. Sprawl puts those values into tension. Let’s take as a given that sprawl is “bad” urbanism, mediocre at best. Realistically, it’s rarely going to be transit-oriented, highly walkable, or architecturally profound. So the question is whether outward, greenfield growth is necessary to achieve affordability. And the answer from urban economics is yes. You can’t get far in making a city affordable without letting it grow outward. Model 1: All hands on deck Let’s start with a nonspatial model where people demand housing space and it’s provided by both existing and new housing. Existing housing doesn’t easily disappear, so the supply curve is kinked. A citywide supply curve is the sum of a million little property-level supply curves. We can split it into two groups: infill and greenfield, which we add horizontally. If demand rises to the new purple line, you can see that the equilibrium point where both infill & greenfield are active is at a lower price & higher quantity than the infill-only line. The only way to get some infill growth to replace some greenfield growth, in this model, is to raise the overall price level. And even then, the replacement is less than 1-for-1. Of course, this is just a core YIMBY idea reversed! In most U.S. cities, greenfield growth has been allowed and infill growth sharply constrained, so that prices are higher, total growth is lower, and greenfield growth is higher than if infill were also allowed. At the most basic level, greenfield growth is simply one of the ways to meet demand. With fewer pumps working, you’ll drain less of the flood. Model 2: Paying for what you demolish Now let’s look at a spatial model where people […]

A friend asked what are the best papers supporting land use liberalization. That’s a broad question, but here are some of my answers. Affordability The basic case for zoning reform, across the political spectrum, is that the rent is too damn high. Michael Manville, Michael Lens, and Paavo Monkkonen give a combative and accessible review of the evidence in their Urban Studies paper (2020). The principal drawback is that it is rapidly becoming dated, as evidence and research come in from more recent reforms. The most important of those may be Auckland’s, which Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy has reported in a few papers, including this Economic Policy Center working paper (2023). Using a synthetic control method (which is not perfect, to be sure), Greenaway-McGrevy finds that upzoned areas had 21 to 33 percentage points less rent growth. A new candidate for the best review of the evidence on zoning reform and affordability is Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine M. O’Regan’s late 2023 working paper, “Supply Skepticism Revisited.” Racial integration Many authors from different disciplines have shown that both the intent and effect of zoning as practiced in the U.S. were racist and classist. That is, zoning policies have separated people by race, homeownership status, and income more than would have occurred in an unregulated market. Allison Shertzer, Tate Twinam, and Randall Walsh’s review of the evidence in Regional Science and Urban Economics (2022) is concise and helpful. However, fewer authors have attempted to show that removing specific zoning restrictions reduces existing patterns of segregation. One is Edward Goetz, in Urban Affairs Review (2021). He makes a qualitative argument. I’m unaware of a good causal, quantitative paper showing how broad upzoning impacts local integration (but I would happily commission it if anyone wants to write it!) Environment & climate Along some […]

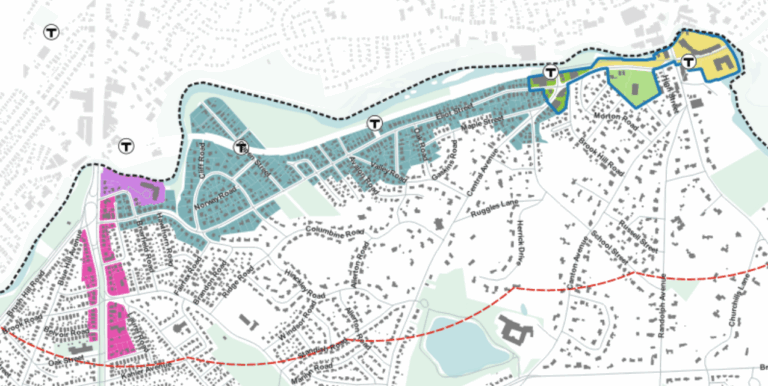

“Wow!” the reporter said, “I knew you from Milton, but I didn’t know you were from East Milton. Tell me what it feels like?” Well, until last week it was not that dramatic. East Milton is an old railroad-commuter neighborhood favored by affluent Boston Irish. It’s separated from the City of Boston by the Neponset River estuary and from the rest of Milton by a sunken interstate highway that makes it more congested and big-city than the rest of town. MBTA Communities In January 2021, Massachusetts passed the first transit-oriented upzoning law of the YIMBY era, now called “MBTA Communities,” “MTBA-C”, or “Section 3A”. Implementing regulations assigned a multifamily zoning capacity to each town. Milton was always going to be one of the toughest cases for MBTA Communities. The northern edge of town is served by the Mattapan Trolley, which John Adams rode to the Boston Tea Party links up to the Red Line at Ashmont. The trolley makes Milton a “rapid transit community”, which means it has to zone for multifamily units equal to 25% of its housing stock. Among the dozen towns in the rapid transit category, Milton is the only one where less than a quarter of current housing units are multifamily; it also has few commercial areas to upzone. East Milton dissents East Milton voters went to the polls on Wednesday and led a referendum rebuke of the plan. In Ward 7, it wasn’t close: 82% opposed the rezoning. The Boston Globe offered a helpful breakdown of the surprisingly varied voting: There are several hypotheses as to why the neighborhood went against rezoning so hard, all probably played a role. East Milton was assigned more than half the net new multifamily zoning capacity despite lacking good transit access. The neighborhood has been in a contentious, multiyear […]

Updated 1/11/24 to add 3 new papers, Wegmann, Baqai, and Conrad (2023), Dobbels & Tavakalov (2023), and Hamilton (2024). The original post was published 3/14/23. A concerted research effort has brought minimum lot sizes into focus as a key element in city zoning reform. Boise is looking at significant reforms. Auburn, Maine, and Helena, Montana, did away with minimums in some zones. And even state legislatures are putting a toe in the water: Bills enabling smaller lots have been introduced [in 2023] in Arizona, Massachusetts, Montana, New York, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. The bipartisan appeal of minimum lot size reform is reflected in Washington HB 1245, a lot-split bill carried by Rep. Andy Barkis (R-Chehalis). It passed the Democratic-dominated House of Representatives by a vote of 94-2 and has moved on to the Senate. City officials and legislators are, reasonably, going to have questions about the likely effects of minimum lot size reductions. Fortunately, one major American city has offered a laboratory for the political, economic, and planning questions that have to be answered to unlock the promise of minimum lot size reforms. Problem, we have a Houston Houston’s reduced minimum lot sizes from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet in 1998 (for the city’s central area) and 2013 (for outer areas). This reform is one of the most notable of our times – and thus has been studied in depth. For a summary treatment, see Emily Hamilton’s 2023 case study. To bring all the existing scholarship into one place, I’ve compiled this annotated bibliography covering the academic papers and some less-formal but informative articles that have studied Houston’s lot size reform. Please inform me of anything I’m missing – I’ll add it. Political economy of Houston’s reform M. Nolan Gray & Adam Millsap (2020). Subdividing the Unzoned City: An Analysis […]

I don’t know how successful artificial intelligence will be. But let’s agree, for the moment, to consider a reasonably optimistic case where AI delivers significant productivity gains across a broad range of tasks – but not in a way that radically alters our Newtonian constraints. What would happen to housing economics and, consequently, housing politics? TL;DR Construction won’t be much affected by AI. Consumers will be richer and spend a bigger share of their incomes on housing. The stakes around housing policy will only grow. Inscriptibility Karl Marx divided the economic world into capital and labor. More recent economists have frequently (and self-regardingly) divided labor into low-skill and high-skill. In an AI world, we need to start talking about inscriptible and uninscriptible labor. I’m using a circular definition on purpose – AI will replace inscriptible labor because inscriptible labor is the type that AI is good at replacing – because I have only a fuzzy idea what AI will be good at. (A diversion) (Why inscriptible rather than legible, in a James C. Scott sense? I thank Bard for the suggestion. Think about visual art – AI is probably no better than humans at guessing what nuances a human artist intended, but it can produce human-quality visual art rich with nuance. Since AI’s value is partly predicated on repetition speed, it will thrive in arenas where failures are costless. Thus, AI may be formulating 99% of new drugs in a few years even if nobody trusts it to perform a simple surgery. That’s an inscriptibility difference, not a legibility difference. The most inscriptible human tasks are presumably those that simpler software replaced long ago, usually called “routine.” The big surprise of 2023 AI was the advances that software made with tasks we have considered creative. The “routine” concept was valuable […]

WASHINGTON – David Paitsel, 42, a former FBI agent, and Brian Bailey, 53, a D.C. real estate developer were sentenced today on bribery and conspiracy charges for their role in schemes involving confidential information held by the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development United States Attorney’s office There are plenty of housing laws you can break. But these grifters were busted only for bribing a city official for information. Otherwise, they used the housing law – the most innocent-sounding of all housing laws – correctly. Washington DC has a strong Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA). When a landlord sells, tenants have the right to match any offer, conceivably buying their own building. That never happens. But TOPA also allows tenants to sell their rights to literally anyone else. The law treats the new owner of the TOPA rights with the same exaggerated deference as a tenant. The TOPA grift goes like this: A TOPA shark, like Paitsel and Bailey, approaches tenants whose building is on the market. The “approach”, as I’ve witnessed it, can be a hand-scrawled note placed in the tenants doors or mailboxes. The tenants rarely know the mechanics of buying a house, let alone utilizing an obscure city-specific TOPA scheme that would have to involve collective action among many tenants. So the sharks offer the tenants a few hundred dollars for their rights. If the offer is accepted, the shark informs the landlord. Now suppose a prospective buyer comes along and offers $1,200,000 for a D.C. sixplex. The landlord must inform the shark, who now has the right to match any bona fide offer on the property. But the shark has no interest in buying – he just demands ten or twenty thousand dollars to surrender the rights. If the landlord resists extortion, the shark […]