Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

My guest this week is Anthony Ling. Anthony is founder and editor of Caos Planejado, a Brazilian website on cities and urban planning. He also founded Bora, a transportation technology startup and is currently an MBA candidate at Stanford University. He graduated Architecture and Urban Planning at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and worked with Isay Weinfeld early in his career. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Be sure to check out Caos Planejado. Whether Portuguese is your native language or you’re interested in Brazilian urban planning issues, it’s a fantastic resource. Learn more about the emergent order of informal favela development. Everyone interested in urban planning should, at the very lease, read the Wikipedia article on Brasilia. Learn more about on-demand transit. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

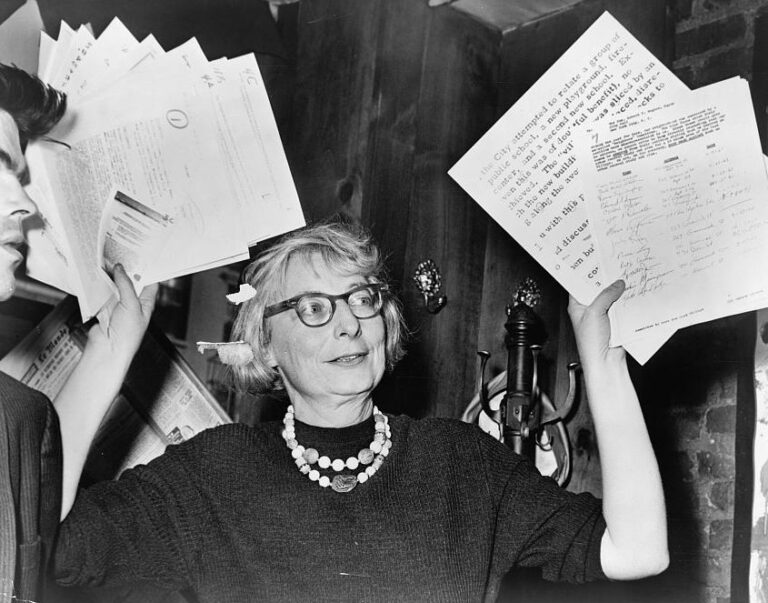

My guest this week is Sanford Ikeda, a professor of economics at SUNY Purchase and a visiting scholar at New York University. He has written extensively on urban economics, policy, and planning. Professor Ikeda introduced me to urban economics and urban planning when he gave a presentation on Jane Jacobs at a FEE summer seminar that I attended back in 2012. Here are a few of the topics we discussed in the episode: If you haven’t already, I highly suggest reading Jane Jacobs. The natural place to start is The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Her other books, including The Economy of Cities and Systems of Survival, explore topics ranging from economics to political philosophy. Professor Ikeda has written extensively on Jane Jacobs. You can read a nice overview here. If you would like to read more, click here for a paper he wrote on F.A. Hayek, Jane Jacobs, and the importance of local knowledge in cities. He is also a regular contributor to Freeman and Market Urbanism. We also discussed William H. Whyte’s famous documentary on public space, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. It’s well worth checking out. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.

If you regularly read about cities, you might notice that Texas cities rarely seem to come up. We make cases for why Detroit is definitely coming back—just you wait! We come up with elaborate theories of how cities can become the next Silicon Valley. We spend hours coming up with a solution to New York City’s costumed panhandler problem. Yet the four urban behemoths of the Lone Star State—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin—remain conspicuously absent from the conversation. Boy, has that changed. Earlier this year I wrote a sprawling defense of Houston. Scott Beyer spent the summer writing a series of articles for Forbes profiling the cool things happening in cities across the state. John Ricco recently launched the “Densifying Houston” Twitter feed and discussed the phenomenon on Greater Greater Washington. Just this past weekend, City Journal released an entire special issue dedicated to Texas. Through all this, many have been surprised to learn that a city like Houston could serve as a model for land-use policy and economic growth for struggling coastal cities. Yet two criticisms regularly seem to come up, at least related to Houston: “Houston is an unplanned hell-hole! It’s proof that land-use liberalization would be a disaster.” “Houston isn’t unplanned! It’s as heavily planned as any other city, just look at the covenants.” Since there seems to be a lot of confusion about land-use regulation and planning in Houston, here’s a quick explainer on what Houston does regulate, doesn’t regulate, and how private covenants shape the city. 1. What Houston Doesn’t Do Houston doesn’t mandate single-use zoning. Unlike every other major U.S. city, Houston doesn’t mandate the separation of residential, commercial, and industrial developments. This means that restaurants, homes, warehouses, and offices are free to mix as the market allows. As many have pointed out, however, market-driven separation of incompatible uses—think […]

When I was scheduling out the first few episodes of the Market Urbanism Podcast, it seemed natural to start with one of Market Urbanism’s favorite topics: the relationship between land-use regulation and rising housing costs in American cities. This week I sit down with Emily Hamilton, a regular Market Urbanism contributor and policy manager at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, to discuss a recent paper she coauthored with Sanford Ikeda, “How Land-Use Regulation Undermines Affordable Housing.” The question I am left pondering: how can we convince homeowners—who have a large vested interest in the current system—to support land-use liberalization? Feel free to share your thoughts on this and other topics in today’s episode in the comment section below or with Emily and I on Twitter. Click here to listen to last week’s episode. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive. A few general updates/requests: I am excited to announce that we are now on all major podcasting platforms: iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. If you like what you’re hearing, go ahead and click “subscribe” and leave a review on your favorite platform. If your preferred podcast platform is missing, let me know in the comments below. How would you improve the podcast? Since my goal here is to provide nice content for the Market Urbanism community, I would like to hear your feedback on the show. Thanks for your patience as I familiarize myself with the technical side of podcasting and grow as an interview. Who is a guest you would like to hear on the show? Let me know in the comment section below. If you prefer to keep your suggestion private, feel free to direct message me on Twitter. As always, thanks for listening! We have a few exciting interviews lined […]

This piece was coauthored by Nolan Gray and Katarina Hall. It’s like Los Angeles, but worse. To many, that’s the mental image of Mexico City: a city of unending traffic, unbearable smog, and unrestrained horizontal expansion. Yet when one walks the streets of Mexico City, a distinct reality comes into view: a city of wide sidewalks and integrated bike lanes, lush parks and cool street tree canopies, and dense, mixed-use urban neighborhoods. As a matter of fact, nearly every neighborhood within Mexico City’s giant ring road—the Circuito Interior—has a walkscore above 95. Many major U.S. cities lack even one neighborhood with such a high score. Even on the outer fringe of Mexico’s sprawling Distrito Federal, neighborhoods often have walkscores upwards of 70, qualifying as “very walkable.” What makes Mexico City so walkable? The first thing an American might notice about Mexico City is just how busy the city’s sidewalks are. It’s a city of 21,339,781, and it shows. But this busyness isn’t a mere side-effect of size; it’s a natural result of the city’s generous sidewalks and high-quality pedestrian infrastructure. Many downtown roads host spacious sidewalks, accommodating an unending sidewalk ballet of commuters, tourists, and street vendors. Wide medians along major boulevards offer both refuge for crossing pedestrians and a public space in which people are encouraged to meet and relax. Many of the city’s busiest downtown areas have been closed to automobile traffic. Mexico City’s main road—Paseo de la Reforma—is reserved on Sundays for pedestrians and cyclists. “Jaywalking” is normal and in many cases is assisted by traffic police—a stark contrast to the near persecution pedestrians often face in U.S. cities. The ample space for pedestrians attracts not only foot traffic but also the people watchers who come to enjoy the vitality, in turn keeping many downtown […]

Phew! It’s finally here. After spending a good chunk of my summer researching podcasting, reaching out to potential guests, and recording my first few episodes, I am excited to announce the launch of the Market Urbanism Podcast. You can currently find the podcast on Soundcloud and PlayerFM. It will be available within the next few days on iTunes, Stitcher, and TuneIn. If there are other podcasting services you would like me to plug the RSS feed into, please let me know in the comment section below. Below, you can find a transcript. Given the amount of extra time it takes to transcribe the typical 30 minute episode, this probably won’t be a regular occurrence. That said, if anyone is interested in taking up this job, and getting some credit as an official member of the Market Urbanism Podcast team, message me on Twitter at @mnolangray. Stay tuned next week for a discussion with Emily Hamilton on the relationship between land-use regulation and housing affordability. Enjoy the show! Welcome to the Market Urbanism podcast, where we’re liberalizing cities from the bottom up. I’m your host Nolan Gray, a writer for Market Urbanism and a graduate student in urban planning. In this first episode I’d like to welcome you to the podcast by answering three questions you’re probably already asking yourself: First, what market urbanism? To give you the short answer, market urbanism is the synthesis of classical liberal thought with urban planning and policy. On the market side of the term, we place a lot of value on empowering individuals, recognizing the importance of economic liberty, and celebrating the complex spontaneous orders that organize human life. On the urbanism side of the term, to put it simply, we love cities. We’re interested in understanding what makes for bustling streets, healthy neighborhoods, and prosperous […]

Even by the bizarre standard set by other fandoms, the fandom surrounding the Fallout video game series is weird. Where your typical human would rather spend a Friday night doing strange things like “hang out with friends” and “go out,” your average Fallout fan is likely spending his or her night asking “Could super mutants exist?” or debating the ethical merits of Fallout 4’s factions. In the spirit of this tradition, we wanted to ask: how realistic are Fallout’s cities? It’s worth first asking, does the Fallout universe even have cities? On the one hand, what we call “cities” in Fallout are quite small. In terms of actual visible inhabitants, even the largest of the Fallout cities—the urban area of New Vegas—has fewer than 150 known residents. Other large communities like Megaton, Rivet City, and Diamond City have approximately 50 residents each. The settlements that dot Fallout 4’s Commonwealth all have maximum populations of 21. Even the earliest known cities—take for example, Jericho—had estimated populations ranging from 2,000 to 3,000 in 9,000 BCE. There are two possible responses to this: First, we could be generous and look at Fallout concept art. After all, what we see in the virtual world of Fallout may fall short of the game designers’ vision of each city. Renditions of Megaton, Diamond City, and Rivet City depict cities with populations likely in the hundreds. In the case of New Vegas, concept art depicts a large city potentially supporting thousands of residents. Each is still smaller than even the earliest cities, but they are hardly the villages we experience in the games. Second, we could set aside population as an issue altogether. In The Urban Revolution, archaeologist V. Gordon Childe sets out 10 general metrics for urban cities. We won’t go through them here, […]

A metropolitan economy, if it is working well, is constantly transforming many poor people into middle-class people, many illiterates into skilled people, many greenhorns into competent citizens. … Cities don’t lure the middle class. They create it. – Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities If you follow urban issues in the press, you might be forgiven for thinking that there are only three cities in America: San Francisco, New York, and Portland. All three are victims of their own success, as rising demand for housing has increased rents to unsustainable levels. Despite their best efforts, from rent control to inclusionary zoning mandates, middle- and lower-class households are increasingly forced to leave these cities as each progressively transforms into a playground of the rich. Yet there is a fourth city, a city which must not be named except to be derided as a sprawling, suburban hellscape. This fourth city has managed to balance a booming economy, explosive population growth, and affordable housing. This city has—as cities have for thousands of years—steadily grown denser, more walkable, and more attractive to low-income migrants seeking opportunity. This city is Houston, and it’s well past time for her to come out of the shadows. Explosive Economic Growth, Booming Population, Functioning Housing Market Before jumping into the nitty-gritty of how Houston has handled explosive growth in the demand for housing, it is worth first getting a handle on the magnitude of the challenge facing the city. When many people think of the Houston economy, they understandably think of large energy companies. Indeed, energy companies dominated Houston’s economy for much of the last century and continue to play a major role today. But in the years following the 1980s oil glut, Houston’s economy has been diversified in large part by startups and emerging small […]

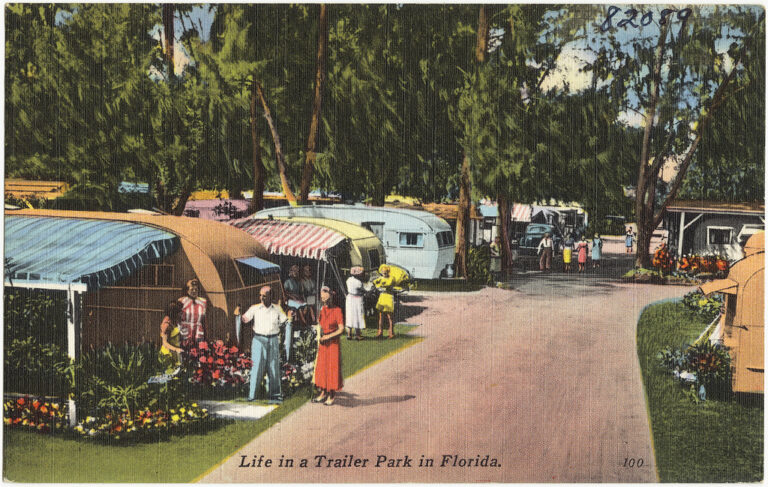

Given that “redneck” and “hillbilly” remain the last acceptable stereotypes among polite society, it isn’t surprising that the stereotypical urban home of poor, recently rural whites remains an object of scorn. The mere mention of a trailer park conjures images of criminals in wifebeaters, moldy mattresses thrown awry, and Confederate flags. As with most social phenomena, there is a much more interesting reality behind this crass cliché. Trailer parks remain one of the last forms of housing in US cities provided by the market explicitly for low-income residents. Better still, they offer a working example of traditional urban design elements and private governance. Any discussion of trailer parks should start with the fact that most forms of low-income housing have been criminalized in nearly every major US city. Beginning in the 1920s, urban policymakers and planners started banning what they deemed as low-quality housing, including boarding houses, residential hotels, and low-quality apartments. Meanwhile, on the outer edges of many cities, urban policymakers undertook a policy of “mass eviction and demolition” of low-quality housing. Policymakers established bans on suburban shantytowns and self-built housing. In knocking out the bottom rung of urbanization, this ended the natural “filtering up” of cities as they expanded outward, replaced as we now know by static subdivisions of middle-class, single-family houses. The Housing Act of 1937 formalized this war on “slums” at the federal level and by the 1960s much of the emergent low-income urbanism in and around many U.S. cities was eliminated. In light of the United States’ century-long war on low-income housing, it’s something of a miracle that trailer parks survive. With an aftermarket trailer, trailer payments and park rent combined average around the remarkably low rents of $300 to $500. Even the typical new manufactured home, with combined trailer payments and park rent, costs […]

When it comes to the impact autonomous cars will have on cities, there’s plenty of room for disagreement. Will they increase or decrease urban densities? Will they help with congestion or make it worse? At the same time, there seems to be widespread agreement on at least two things: First, far fewer people will own cars. Second, we are not going to need nearly as much parking. By combining the technology of autonomous cars with the business model of transportation network companies like Uber and Lyft, low-cost, on-demand ride-hailing and dynamic routing bus lines could eliminate the need to keep an unused car hanging around for most of the day. When that happens, we will need far fewer parking spaces, turning on-street parking into wider sidewalks and bike lanes and surface lots and parking ramps into residential and commercial uses. So how does the humble American residential garage fit into all this? On its face, the garage is little more than the sheltered parking space that comes with most single-family homes. Yet the garage holds a certain mythological status in the American psyche: It gave rise to iconic American brands like Disney, Harley Davidson, and Mattel. It offered a space in which the firms that would launch the digital economy could get their start, including HP and Apple. Google and Microsoft, which both started in garages, maintain “garage” work spaces to this day in order to cultivate innovation. By providing a flexible space in which knowledge, free time, and ambition can transform into entrepreneurial innovation, the garage has played a crucial role in the American economy. At least in the near term, garages are not going anywhere. Unlike municipal governments and large private landowners who will likely face immediate political and market pressures to retool their parking spaces, many homeowners are structurally stuck with their garages. Millions of garages could go unused, occasionally kept active by automobile hobbyists, most likely turning into de facto storage units. But it doesn’t have to be […]