Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

NYU professor Arpit Gupta has channeled the annoyance of economists into a blog post directly calling out the Strong Towns "growth Ponzi scheme" line of argument.

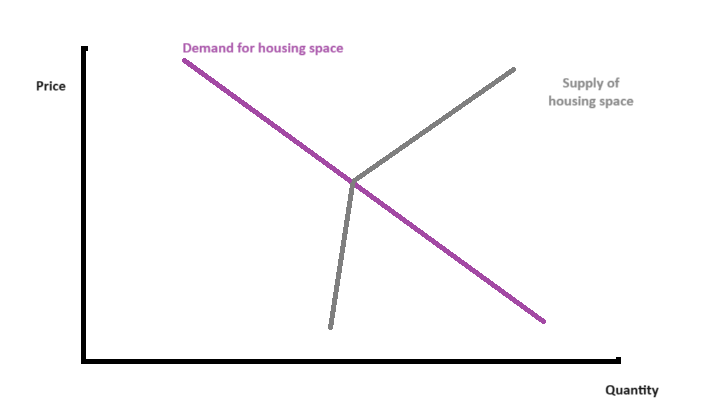

Should YIMBYs support or oppose greenfield growth? Two basic values animate most YIMBYs: housing affordability and urbanism. Sprawl puts those values into tension. Let’s take as a given that sprawl is “bad” urbanism, mediocre at best. Realistically, it’s rarely going to be transit-oriented, highly walkable, or architecturally profound. So the question is whether outward, greenfield growth is necessary to achieve affordability. And the answer from urban economics is yes. You can’t get far in making a city affordable without letting it grow outward. Model 1: All hands on deck Let’s start with a nonspatial model where people demand housing space and it’s provided by both existing and new housing. Existing housing doesn’t easily disappear, so the supply curve is kinked. A citywide supply curve is the sum of a million little property-level supply curves. We can split it into two groups: infill and greenfield, which we add horizontally. If demand rises to the new purple line, you can see that the equilibrium point where both infill & greenfield are active is at a lower price & higher quantity than the infill-only line. The only way to get some infill growth to replace some greenfield growth, in this model, is to raise the overall price level. And even then, the replacement is less than 1-for-1. Of course, this is just a core YIMBY idea reversed! In most U.S. cities, greenfield growth has been allowed and infill growth sharply constrained, so that prices are higher, total growth is lower, and greenfield growth is higher than if infill were also allowed. At the most basic level, greenfield growth is simply one of the ways to meet demand. With fewer pumps working, you’ll drain less of the flood. Model 2: Paying for what you demolish Now let’s look at a spatial model where people […]

Aaron Renn has an interesting article in Governing. He suggests that even though urban cores are responsible for a significant chunk of the regional tax base, “[t]he city is dependent on the suburbs, too.” In particular, he notes that downtowns are dependent on a labor and consumer pool that extends far beyond downtown. For example, Manhattan is valuable because it is at the center of a vast region. He’s right- if you define “suburb” broadly as “everything that isn’t downtown.” A downtown that isn’t surrounded by neighborhoods is just a small downtown. But that isn’t always the way Americans understand suburbs. If you think of suburbs as “towns outside the city with a different tax base that are usually much richer than the city” , suburbs aren’t good for the city at all. Because of the growth of suburbs, cities have stunted tax bases because they have a disproportionate share of the region’s poverty, and have to pay for a disproportionate share of poverty-related government programs. By contrast, if cities resembled the cities of 100 years ago that included nearly all of their regional population, they would have stronger tax bases. (This may seem like a pipe dream to residents of northeastern cities trapped within their 1950 borders, but plenty of Sun Belt cities include huge amounts of suburb-like territory). Similarly, if you think of suburbs as “places where most people have to drive to get anywhere” their existence is not so good for the city. When suburbanites drive into the city they create pollution, and they lobby for highways that make it easier for them to create even more (while taking up land that city residents would otherwise use for businesses and housing). And when jobs move to car-dependent suburbs, that devalues city living, either because carless city residents […]

Our tax code favors suburbia. Homeownership, greenfield development, and sprawl receive preferential tax treatment, and the market responds to incentives built into the code. As a result, a disproportionate amount of capital flows to those investments. In many cases, it has been an unintentional side effect of pursuing other goals. The combined effect is that our tax system plays a huge role in shaping our communities. Its influence is an important factor to understanding how residential design in the US became what it is today.

The government exercises tremendous power over residential design in the US. Its influence is nearly invisible, because it works through complex financing programs, insurance incentives, and secondary markets. These mechanisms go unnoticed, but their effect is hard to miss—they remade the United States into a nation of sprawling suburbs. This is the second post in a series about government policies that encouraged suburban growth in the US. You can find the first post here. What image springs to mind when you picture “federally subsidized housing”? Most people imagine a low-income public housing tower, a homeless shelter, or a shoddy apartment building. Nope—suburban homeowners are the single biggest recipient of housing subsidies. As a result, suburbs dominate housing in the United States. For decades, federal finance regulations incentivized single-family homes through three key mechanisms: Insurance, National mortgage markets, and New standards for debt structuring The housing market hides these details from the typical home buyer. As a result, most people are unaware of these subsidies. But their effects are striking—they determined the location and shape of development across America for generations. A New Deal to restore the housing industry Debt has a negative connotation these days. Credit cards, student loans, and auto loans are the anchors that keep many Americans in debt for most of their life. Meanwhile, we view mortgages very differently—they are seen as an investment, a symbol of adulthood, and a sign of financial stability. This was not always the case. In the early 1900s, mortgages were just like any other kind of debt. Nowadays payments are spread out over decades, but back then they came due all at once after a few years. Most people didn’t have enough cash at the end of the term. It was standard to pay back some and negotiate a new loan for […]

This is the first article of a five-part series on suburbia in the United States. In primary school, one of my friends lived in a duplex. This fact blew my mind. To my inexperienced 7-year-old mind, a duplex barely registered as a house. Her family shared a driveway with their neighbors, and their yard was tiny. It was the first house I’d ever seen that shared a wall with its neighbors. I’d seen apartments of course, but in my mind those were temporary, for people who who were saving up to buy a “real” home. I couldn’t understand that some people might actually prefer to live in something besides a private home, because I’d never come across it before. Median income in American cities tends to rise at about 8 percent per mile as one moves away from the business district. My mental model of the world was pretty typical for an American child brought up in a single-family home. It’s easy to see why—US residential development is dominated by suburbs, and home ownership is touted as the ultimate symbol of prosperity. Other types of dwellings tend to be for young people starting out in life or low income households unable to afford a place of their own. The popular image of the American Dream includes a white picket fence and a car, not an apartment and a subway pass. This is in stark contrast with most other countries. The French word for suburb is banlieue, and it has come to connote poverty and social isolation, because that is where immigrants and the poor tend to live. They’ve been known as “red suburbs” because of their tendency to vote Communist. Meanwhile, the wealthy live in the city center. In South Africa, the inner city is reserved for the privileged white […]

Hovering somewhere just beyond all the land use zoning regulations, building codes, finance mechanisms, aspirational comprehensive municipal plans, state mandates, and endless NIMBYism lies… reality. If you happen to want to live in certain parts of coastal California you need to come to grips with a serious supply and demand imbalance. Demand is endless. Supply is highly constrained. And there’s a huge amount of money on the table. Horizontal growth is essentially verboten. A powerful coalition of existing property owners, environmental groups, resource allocation schemes, and multi-tiered government regulations stymie new greenfield development. The personal interests of conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats line up exactly when anyone attempts to build anything near them. “Over my dead body.” It’s understood that if a town accepts endless low density horizontal development the overall quality of the area will decline. You can’t have expansive large scale suburbia without paving over the countryside, creating a great deal of traffic congestion, and inducing strip mall blight. At the same time, no one wants infill development on existing not-so-great property that’s already been paved over and degraded. The neighborhood associations break out the pitch forks and firebrands at the suggestion of multi-story condos or (Heaven forbid) apartment buildings. The population of any older suburb could double or triple without using a single inch of new greenfield land. But that kind of growth is feared and hated. So the aging muffler shops and parking lots linger in the middle of a massive housing crisis. Google Google Google On the other hand there’s radically less regulatory or community push back against expanding and improving existing suburban homes. Google Street View makes it possible to observe how a little post war tract home was transformed into a substantially larger residence. This kind of growth is entirely acceptable. The building […]

I’ve been meaning to address the public education system’s complex role in land use patterns, and found that Murray Rothbard does a better job in his 1973 manifesto, For a New Liberty than I ever could. In summary, locally-funded public education is an engine of geographical segregation, which encourages flight from urban areas, and was a driving motivation for the popular acceptance of exclusionary zoning in newer suburbs. As a result, wealth is consistently concentrated geographically, and housing affordability is at odds with these restrictions of supply intended to exclude poorer people from draining the property tax base. Here’s a paragraph from the chapter on education: The geographical nature of the public school system has also led to a coerced pattern of residential segregation, in income and consequently in race, throughout the country and particularly in the suburbs. As everyone knows, the United States since World War II has seen an expansion of population, not in the inner central cities, but in the surrounding suburban areas. As new and younger families have moved to the suburbs, by far the largest and growing burden of local budgets has been to pay for the public schools, which have to accommodate a young population with a relatively high proportion of children per capita. These schools invariably have been financed from growing property taxation, which largely falls on the suburban residences. This means that the wealthier the suburban family, and the more expensive its home, the greater will be its tax contribution for the local school. Hence, as [p. 133] the burden of school taxes increases steadily, the suburbanites try desperately to encourage an inflow of wealthy residents and expensive homes, and to discourage an inflow of poorer citizens. There is, in short, a breakeven point of the price of a house beyond which a […]

Paul Krugman wrote an op-ed this morning how the US living and transportation patterns will not cope with high oil prices as well as European cities: Changing the geography of American metropolitan areas will be hard. For one thing, houses last a lot longer than cars. Long after today’s S.U.V.’s have become antique collectors’ items, millions of people will still be living in subdivisions built when gas was $1.50 or less a gallon. Infrastructure is another problem. Public transit, in particular, faces a chicken-and-egg problem: it’s hard to justify transit systems unless there’s sufficient population density, yet it’s hard to persuade people to live in denser neighborhoods unless they come with the advantage of transit access. Over the long-run the US can adapt it’s living patterns to expensive oil by curbing it’s habit of subsidizing roadways. However, only if density restrictions soften accordingly. If drivers were responsible for the full costs of their location and transportation decisions, they would gradually locate to more European-like locations. This will naturally increase the demand for transit. Private investment and entrepreneurship under such conditions should be able to provide innovative solutions to the chicken-and egg problem Krugman is concerned about.

Wall Street Journal Blog: Are McMansions Making Some Americans Unhappy?