Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

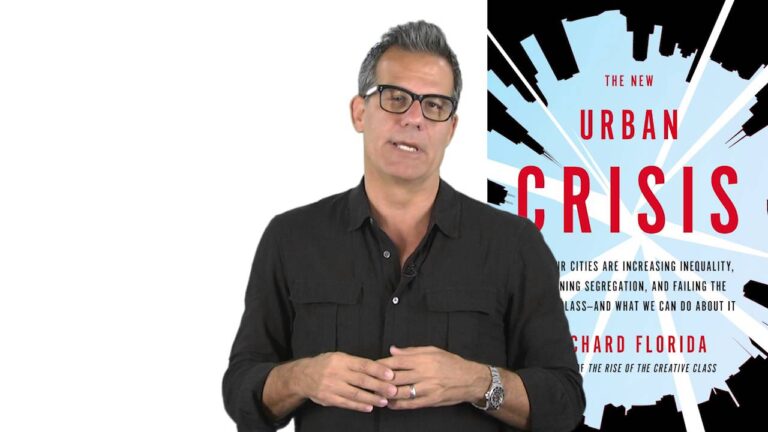

I just finished reading Richard Florida’s new book, The New Urban Crisis. Florida writes that part of this “crisis” is the exploding cost of housing in some prosperous cities. Does that make him a market urbanist? Yes, and no. On the one hand, Florida criticizes existing zoning laws and the NIMBYs who support them. He suggests that these policies not only raise housing prices, but by doing so harm the economy as a whole. For example, he writes that if “everyone who wanted to work in San Francisco could afford to live there, the city would see a 500 percent increase in jobs… On a national basis, [similar results] would add up to an annual wage increase of $8775 for the average worker, adding 13.5 percent to America’s GNP – a total gain of nearly $2 trillion” (p 27). On the other hand, Florida is not ready to endorse the idea that “we can make our cities more affordable… simply by getting rid of existing land use restrictions” because “the high cost of land in superstar neighborhoods makes it very hard if not impossible, for the private market to create affordable housing in their vicinity. Combine the high costs of land with the high costs of high-rise construction and the result is more high-end luxury housing.” (p. 28). I don’t find his point persuasive, for a variety of reasons. First, as I have written elsewhere, land prices are often quite volatile. Second, the overwhelming majority of any region’s housing is not particularly new; even in high-growth Houston, only 2 percent of housing units were built after 2010. Thus, new market-rate housing is likely to affect rents by affecting the price of older housing, rather than by bringing new cheap units into the market. Florida also writes that “too much density can […]

Washington, D.C. has a monopoly on many things. Bad policy, unfortunately, isn’t among them. Last month, a development corporation in Lexington, Kentucky installed a shipping container house in an economically distressed area of town to improve housing affordability. The corporation is a private non-profit, though a line near the end of this article indicates that the project received public support: “The project is funded through an assortment of grants from the city’s affordable housing fund [and two philanthropic organizations].” Shipping container projects designed to improve housing affordability aren’t limited to my Old Kentucky Home: a quick Google search reveals that the idea of using shipping containers to put a dent in housing costs is popular among policymakers and philanthropists all over the world. The sad reality is that shipping container homes likely have little—if any—role to play in handling the nationwide housing affordability problem. Aside from being inefficient for housing generally, there’s decent evidence that shipping containers appeal far more to reasonably well-off, single urbanites than to working families in need of affordable housing. More broadly, the belief that these projects could address the growing affordability crisis hints at a profound misunderstanding of the nature of the problem and distracts policymakers from viable solutions. Before digging into the meatier problems, it’s worth looking first at the problems with the structures themselves. I’ll yield to an architect: Housing is usually not a technology problem. All parts of the world have vernacular housing, and it usually works quite well for the local climate. There are certainly places with material shortages, or situations where factory built housing might be appropriate—especially when an area is recovering from a disaster. In this case prefab buildings would make sense—but doing them in containers does not. The source goes on to detail the enormous costs associated with zoning approval, insulation, and utilities. Then there’s the somewhat obvious fact that they’re small. As in, 144 square […]