Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Updated 1/11/24 to add 3 new papers, Wegmann, Baqai, and Conrad (2023), Dobbels & Tavakalov (2023), and Hamilton (2024). The original post was published 3/14/23. A concerted research effort has brought minimum lot sizes into focus as a key element in city zoning reform. Boise is looking at significant reforms. Auburn, Maine, and Helena, Montana, did away with minimums in some zones. And even state legislatures are putting a toe in the water: Bills enabling smaller lots have been introduced [in 2023] in Arizona, Massachusetts, Montana, New York, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. The bipartisan appeal of minimum lot size reform is reflected in Washington HB 1245, a lot-split bill carried by Rep. Andy Barkis (R-Chehalis). It passed the Democratic-dominated House of Representatives by a vote of 94-2 and has moved on to the Senate. City officials and legislators are, reasonably, going to have questions about the likely effects of minimum lot size reductions. Fortunately, one major American city has offered a laboratory for the political, economic, and planning questions that have to be answered to unlock the promise of minimum lot size reforms. Problem, we have a Houston Houston’s reduced minimum lot sizes from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet in 1998 (for the city’s central area) and 2013 (for outer areas). This reform is one of the most notable of our times – and thus has been studied in depth. For a summary treatment, see Emily Hamilton’s 2023 case study. To bring all the existing scholarship into one place, I’ve compiled this annotated bibliography covering the academic papers and some less-formal but informative articles that have studied Houston’s lot size reform. Please inform me of anything I’m missing – I’ll add it. Political economy of Houston’s reform M. Nolan Gray & Adam Millsap (2020). Subdividing the Unzoned City: An Analysis […]

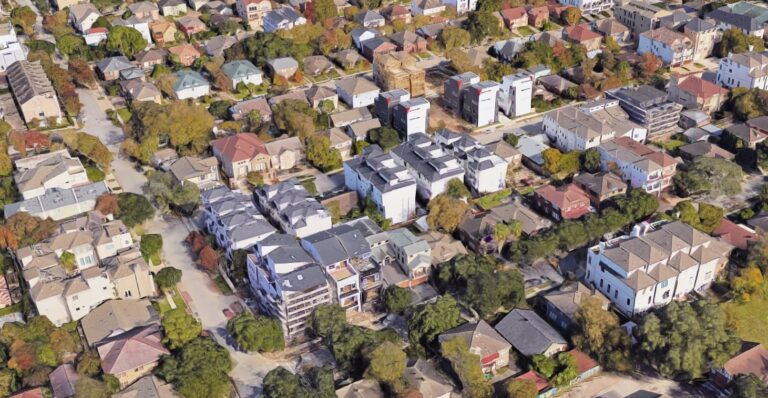

A trip to Houston reveals how a city can design without shame, urbanize around cars, and achieve privacy in a context of radical integration.

Someone just posted a video on Youtube using Houston, Texas as an argument in favor of zoning. The logic of the video is: Houston is horrible; Houston has no zoning; therefore every city should have conventional zoning. This video and its logic are impressively wrong, for several reasons. First, I’ve been to Houston and most of what I saw looks nothing like the video – there are plenty of blocks dominated by houses and the occasional condo. Second, most of the photos in the video could have easily happened in a zoned city, because one block in a neighborhood could be residential and the next block could be commercial, so the commercial or industrial activities can be easily viewable from the residential areas (not that anything is wrong with that). Third, most other automobile-dependent cities aren’t any prettier than Houston; a strip mall in Houston doesn’t look any worse than a strip mall in Atlanta. Fourth, it completely overlooks the negative side effects of zoning as it is practiced in most of the United States (many of which have been addressed more than once on this site). Typically, residential zones are so enormous that most of their residents cannot walk to a store or office. Moreover, density limits everywhere limit the supply of modest housing, thus creating housing shortages and homelessness. Finally, Houston’s negative characteristics are partially a result of government spending and regulation; as I have written elsewhere, that city has historically had a wide variety of anti-walkability policies, so it is far more regulated than the video suggests.

How much should we blame planning for the degree to which cities sprawl? As much time as we (justifiably) spend here on this blog explaining how conventional U.S. planning drives excessive sprawl, it’s worth periodically remembering that, at the end of the day, the actual extent of the horizontal expansion of cities is largely outside the control of urban planning. Consider Houston. Whenever I say anything nice about Houston’s relatively liberal approach to land-use regulation, someone invariably comments some variation of the following: “Yes, that’s all well and good in theory. But in practice, heavily regulated cities like Boston are far more urban and walkable, so maybe relaxed land-use regulations aren’t so great.” Indeed, most of Houston is classic sprawl. But this begs the question: to what extent can urban planning policy be blamed for sprawl? The urban economist Jan Brueckner, drawing on an extensive literature, distinguishes between the “fundamental forces” that naturally drive urban growth outward and the market failures that push this growth beyond what might occur in an appropriately regulated market. (For the purposes of this post, I’ll be using “sprawl” and “horizontal urban expansion” interchangeably. In the same paper, Brueckner thoughtfully distinguishes the two.) The latter, urban planners can address. The former, not so much. Let’s look first at the “fundamental” variables that planners have little to no control over. Brueckner identifies three: population growth, rising income, and falling commuting costs. The first variable is obvious: as cities grow, demand for all housing goes up, and some of that housing goes out on the periphery regardless of planning policy. Metropolises like Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta are currently experiencing 2% population growth every year, meaning they are on track to double in population in the next 35 years. You would expect a lot of horizontal expansion, all else […]

In most of my discussions of Houston here on the blog, I have always been quick to hedge that the city still subsidizes a system of quasi-private deed restrictions that control land use and that this is a bad thing. After reading Bernard Siegan’s sleeper market urbanist classic, “Land Use Without Zoning,” I am less sure of this position. Toward this end, I’d like to argue a somewhat contrarian case: subsidizing private deed restrictions, as is the case in Houston, is a good idea insomuch as it defrays resident demand for more restrictive citywide land-use controls. For those of you who haven’t read my last four or five wonky blog posts on land-use regulations in Houston (what else could you possibly be doing?), here is a quick refresher. Houston doesn’t have conventional Euclidean zoning. Residents voted it down three times. However, Houston does have standard subdivision and setback controls, which serve to reduce densities. The city also enforces high minimum parking requirements outside of downtown. On top of these standard land-use regulations, the city heavily relies on private deed restrictions. Also known as restrictive covenants, these are essentially legal agreements among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property, often set up by a developer and signed onto as a condition for buying a home in a particular neighborhood. In most cities, deed restrictions cover superfluous lifestyle preferences not already covered by zoning, including lawn maintenance and permitted architectural styles. In Houston, however, these perform most of the functions normally covered by zoning, regulating issues such as permissible land uses, minimum lot sizes, and densities. Houston’s deed restrictions are also different in that they are heavily subsidized by the city. In most cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by parties to a deed, typically organized as a […]

Houston doesn’t have zoning. As I have written about previously here on the blog, this doesn’t mean nearly as much as you would think. Sure, Houston’s municipal government doesn’t segregate uses or expressly regulate densities. But as my Market Urbanism colleague Michael Lewyn has documented, city officials do regulate lot sizes, setbacks, and parking requirements. They also enforce private deed restrictions, which blanket many of the city’s residential neighborhoods. A deed restriction is a legal agreement among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property. In most cities, deed restrictions are purely private and often fairly marginal, adding rules on top of zoning that property owners must follow. But in Houston, deed restrictions do most of the heavy lifting typically covered by zoning, including delineating permissible uses and design standards. Whenever I point out that Houston has relatively light land-use regulations (and is enjoying the benefits), folks often respond that the city’s deed restrictions are basically zoning. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Before I turn to the essential differences, it’s worth first observing how Houston’s deed restrictions are like any other city’s zoning. First, like zoning, Houston’s deed restrictions are almost universally designed to prop up the values of single-family houses. Despite the weak evidence for a use segregation-property values connection, this justification for zoning goes back to the program’s roots in the 1920s. Many of Houston’s nicest residential neighborhoods, like River Oaks and Tanglewood, follow this line of thinking, enforcing tight deed restrictions on residents that come out looking a lot like zoned neighborhoods in nearby municipalities like Bellaire and Jersey Village. Second, both zoning and Houston’s deed restrictions are enforced by government officials at taxpayer expense. In most other cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by a private group like a homeowners association, […]

In my regular discussions of U.S. zoning, I often hear a defense that goes something like this: “You may have concerns about zoning, but it sure is popular with the American people. After all, every state has approved of zoning and virtually every city in the country has implemented zoning.” One of two implications might be drawn from this defense of Euclidean zoning: First, perhaps conventional zoning critics are missing some redeeming benefit that obviates its many costs. Second, like it or not, we live in a democratic country and zoning as it exists today is evidently the will of the people and thus deserves your respect. The first possible interpretation is vague and unsatisfying. The second possible interpretation, however, is what I take to really be at the heart of this defense. After all, Americans love to make “love it or leave it” arguments when they’re in the temporary majority on a policy. But is Euclidean zoning actually popular? The evidence for any kind of mass support for zoning in the early days is surprisingly weak. Despite the revolutionary impact that zoning would have on how cities operate, many cities quietly adopted zoning through administrative means. Occasionally city councils would design and adopt zoning regimes on their own, but often they would simply authorize the local executive to establish and staff a zoning commission. Houston was among the only major U.S. city to put zoning to a public vote—a surefire way to gauge popularity, if it were there—and it was rejected in all five referendums. In the most recent referendum in 1995, low-income and minority residents voted overwhelmingly against zoning. Houston lacks zoning to this day. Meanwhile, the major proponents of early zoning programs in cities like New York and Chicago were business groups and elite philanthropists. Where votes were […]

You wake up thirty minutes before your alarm, jerking up after having a nightmare about a car crash. Reluctantly, you clean up, eat breakfast, and hop into your car. Work is only three mile away—easy biking distance—and there are 15 or so people in your neighborhood who work where you work—enough for a commuter bus make sense. But alas, the city required the developer to provide two parking spaces for your townhouse and the cost is hidden somewhere in your mortgage, so why not use it? After spending thirty minutes traveling three miles on the freeway—at least we live in the Golden Age of Podcasting, right?—you arrive at your suburban office park and pull into the garage. The parking is “free,” meaning that your pay has already been docked to cover the cost of the space, so why not use it? Your girlfriend calls shortly after lunch, asking if you want to go on a double dinner date with her friends to a new BBQ place downtown. You agree to join. You’re starving—you left lunch at home and it’s just too time consuming to drive to a decent place—so you hustle downtown. You arrive first, only to find out that there is only on-street parking. Downtown is, after all, exempt from parking requirements, and since street parking is “free,” it’s impossible to find a space during dinner time. You call your dinner partners—each of them is driving separately from work—and suggest another BBQ place downtown that offers subsidized garage parking. This place is a little more expensive, since the restaurateur has to cover some of the cost of offering parking, but you’re all hungry and don’t want to deal with the headache of cruising for street parking. Eventually you all meet and enjoy a nice meal, speculating about how traffic […]

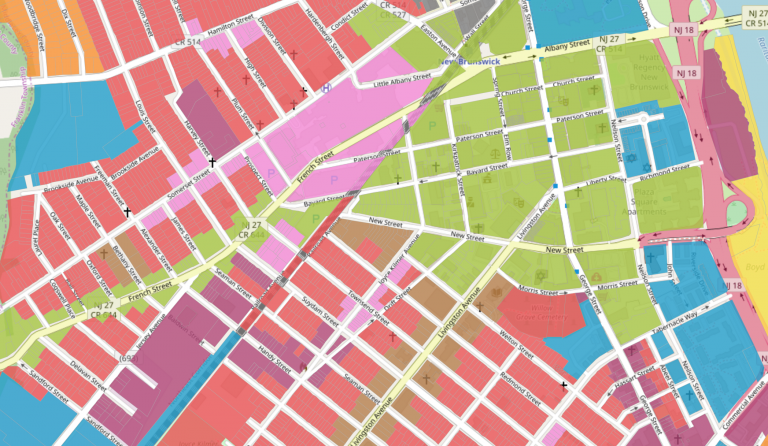

If you regularly read about cities, you might notice that Texas cities rarely seem to come up. We make cases for why Detroit is definitely coming back—just you wait! We come up with elaborate theories of how cities can become the next Silicon Valley. We spend hours coming up with a solution to New York City’s costumed panhandler problem. Yet the four urban behemoths of the Lone Star State—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin—remain conspicuously absent from the conversation. Boy, has that changed. Earlier this year I wrote a sprawling defense of Houston. Scott Beyer spent the summer writing a series of articles for Forbes profiling the cool things happening in cities across the state. John Ricco recently launched the “Densifying Houston” Twitter feed and discussed the phenomenon on Greater Greater Washington. Just this past weekend, City Journal released an entire special issue dedicated to Texas. Through all this, many have been surprised to learn that a city like Houston could serve as a model for land-use policy and economic growth for struggling coastal cities. Yet two criticisms regularly seem to come up, at least related to Houston: “Houston is an unplanned hell-hole! It’s proof that land-use liberalization would be a disaster.” “Houston isn’t unplanned! It’s as heavily planned as any other city, just look at the covenants.” Since there seems to be a lot of confusion about land-use regulation and planning in Houston, here’s a quick explainer on what Houston does regulate, doesn’t regulate, and how private covenants shape the city. 1. What Houston Doesn’t Do Houston doesn’t mandate single-use zoning. Unlike every other major U.S. city, Houston doesn’t mandate the separation of residential, commercial, and industrial developments. This means that restaurants, homes, warehouses, and offices are free to mix as the market allows. As many have pointed out, however, market-driven separation of incompatible uses—think […]

A metropolitan economy, if it is working well, is constantly transforming many poor people into middle-class people, many illiterates into skilled people, many greenhorns into competent citizens. … Cities don’t lure the middle class. They create it. – Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities If you follow urban issues in the press, you might be forgiven for thinking that there are only three cities in America: San Francisco, New York, and Portland. All three are victims of their own success, as rising demand for housing has increased rents to unsustainable levels. Despite their best efforts, from rent control to inclusionary zoning mandates, middle- and lower-class households are increasingly forced to leave these cities as each progressively transforms into a playground of the rich. Yet there is a fourth city, a city which must not be named except to be derided as a sprawling, suburban hellscape. This fourth city has managed to balance a booming economy, explosive population growth, and affordable housing. This city has—as cities have for thousands of years—steadily grown denser, more walkable, and more attractive to low-income migrants seeking opportunity. This city is Houston, and it’s well past time for her to come out of the shadows. Explosive Economic Growth, Booming Population, Functioning Housing Market Before jumping into the nitty-gritty of how Houston has handled explosive growth in the demand for housing, it is worth first getting a handle on the magnitude of the challenge facing the city. When many people think of the Houston economy, they understandably think of large energy companies. Indeed, energy companies dominated Houston’s economy for much of the last century and continue to play a major role today. But in the years following the 1980s oil glut, Houston’s economy has been diversified in large part by startups and emerging small […]