Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

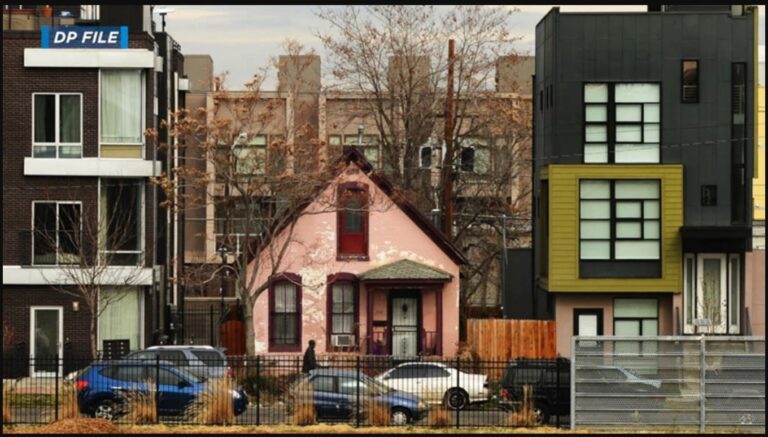

In many cities, poor people occupy valuable urban land close to downtown jobs, amenities, and transit. They can afford to live there because the housing stock in inner areas is usually older. If it hasn’t been completely renovated, the result can be quite cheap, even if the land is pretty valuable. In areas where there’s already some gentrification pressure, landlords face a timing problem: they can renovate (or sell to a developer) now, and cash out. Or they can hoard the property and wait until prices rise, supplying low-cost housing in the meantime. Land value taxes are specifically designed to penalize the hoard-and-wait approach by raising the annual tax cost of sitting on valuable land. It is specifically designed to accelerate neighborhood change. That’s the point. That’s what it says on the tin. Gentrification isn’t the only urban problem, and maybe it’s a small enough urban problem that a land value tax is a good idea anyway. But I think most of the benefits of Georgism can be unlocked with George-ish schemes (like renovation abatements or vacant land taxes) that are more narrowly designed.

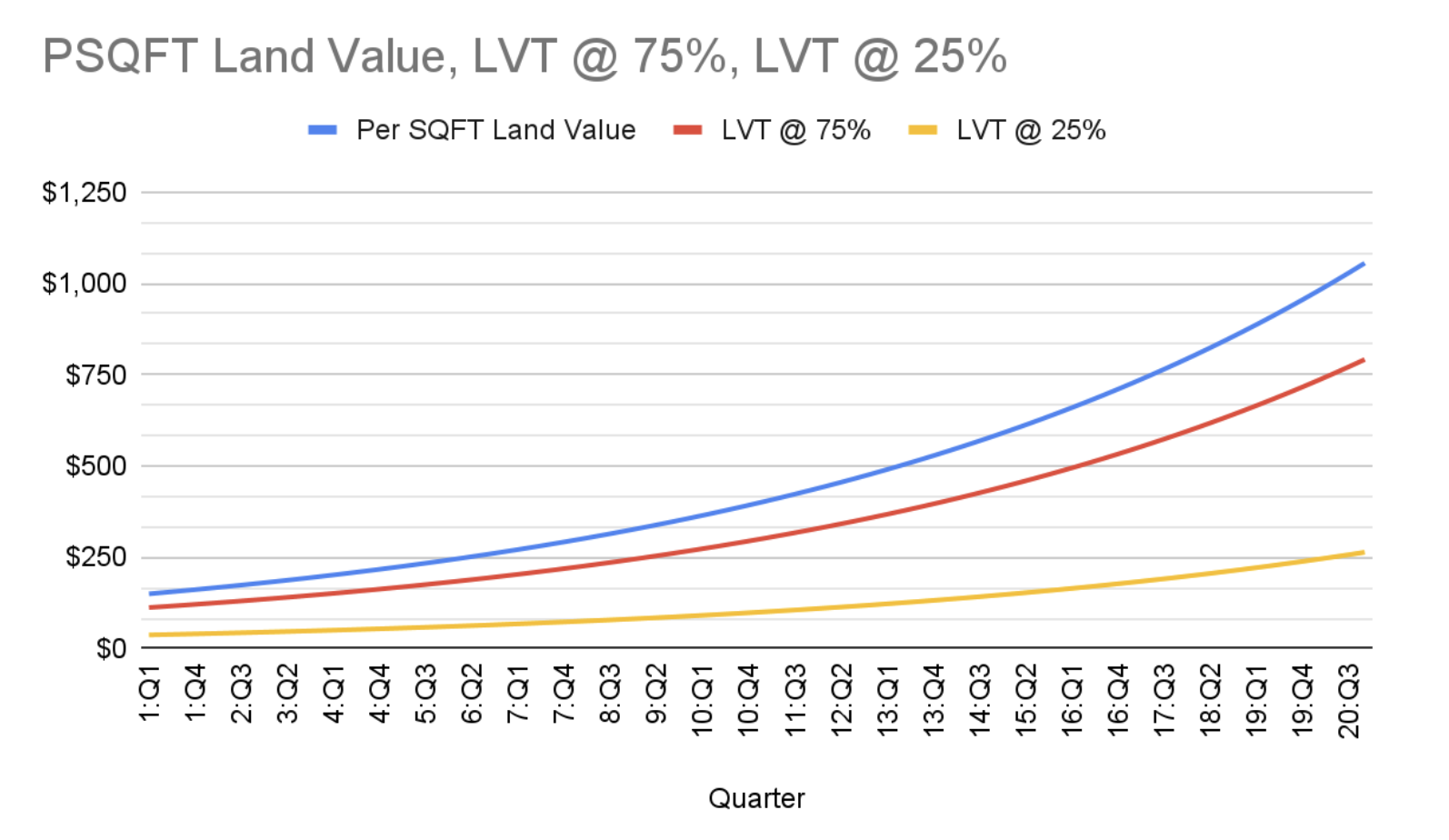

Georgists assert that a Land Value Tax (LVT) ensures land is always put to its most efficient use. They claim that increased carrying costs deter speculation. And if valuable land is never held out of use, society is better off. I think the story about incentives is correct. But I question whether pulling development forward in time is definitionally more efficient. In a world with transaction costs, tradeoffs abound and it’s worth thinking through the implications of an LVT. A Tale of Two Cities Picture a growing local economy with increasing land values and an LVT. Now suppose we split the time stream and create two parallel universes with different tax rates. In scenario A, we apply an LVT at 75%; in scenario B the LVT is set at 25%. There are two important questions here: 1) When will a given parcel be forced into development? 2) What intensity of development will the parcel support at the moment it’s put into productive use? To answer our first question, we look at the tax curves and make some assumptions. Suppose carrying costs push land into productive use at $250 psqft in LVT costs, scenario (a)’s parcel goes into development around year 9 at a $331 psqft. Scenario (b)’s parcel doesn’t see development until year 20 and a ~$1K psqft value. Given the delta between year 9 and year 20’s psqft valuations, we could expect to see different intensities of development. We’re now left with the question of whether a duplex in nine years is better than a mid-rise in twenty. Appropriating the full rental value of land would pull development forward, but that doesn’t definitionally lead to it being put to its highest and best use. Highest and best is contingent upon what time scale we’re optimizing for and that choice […]