Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Maya Dukmasova recently published at Slate an interesting piece about the potential for current trends in affordable housing policy to tear apart the social capital of low-income people. She makes the Ostromian point that policymakers’ lack of understanding of the informal institutions that govern communities makes it likely that government housing policies are likely to have unintended consequences. While Dukmasova aptly characterizes some of the problems with American anti-poverty programs to date, she gets some key history wrong. In particular, she writes: Part of the liberal establishment’s failure to address this problem stems from its inability to embrace truly progressive understandings of poverty. Those advocating for solutions to poverty rarely speak about the way our economy and social infrastructures entrench it. Rather, much of liberals’ efforts have been crippled by unexamined and unchallenged beliefs that the spaces where poor people of color live are morally compromised, beliefs summed up by one well-intentioned but ultimately damaging term: concentrated poverty. In fact, the programs that she criticizes directly grew out of progressive scholarship and politics. Nineteenth century progressives set their sights on demolishing tenements occupied by low-income, immigrant populations with the goal of relocating residents to suburban homes deemed healthier and better for the morals of their inhabitants. Jacob Riis’ influential work in How the Other Half Lives fueled a progressive movement to eradicate tenement housing, with activists motivated both by altruism toward the poor and by a fear of disease and cultural changes that immigrant-dominated neighborhoods brought. Riis became one of the first reformers demanding that “light and air” be a key consideration in new construction. While he used this phrase to campaign against unventilated tenements that actually did create unhealthy indoor conditions indoors, it ultimately provided the policy rationale for the the New York 1916 Zoning Resolution that would limit building height and massing to protect outdoor light and air, as if shade is […]

Over at Greater Greater Washington, Ms. Cheryl Cort attempts to temper expectations of what she calls the “libertarian view (a more right-leaning view in our region)” on affordable housing. It is certainly reassuring to see the cosmopolitan left and the pro-market right begin to warm to the benefits of liberalization of land-use. Land-use is one area the “right,” in it’s fear of change, has failed to embrace a widespread pro-market stance. Meanwhile, many urban-dwellers who consider themselves on the “left” unknowingly display an anti-outsider mentality typically attributed to the right’s stance on immigration. Unfortunately, in failing to grasp the enormity of the bipartisan-caused distortion of the housing market, Ms. Cort resigns to advocate solutions that fail to deliver widespread housing affordability. Yes, adding more housing must absolutely be a part of the strategy to make housing more affordable. And zoning changes to allow people to build taller and more usable space near transit, rent out carriage houses, and avoid expensive and often-unnecessary parking are all steps in the right direction. But some proponents go on to say relaxing zoning will solve the problem all on its own. It won’t. Well, if “relaxing” zoning is the solution at hand, she may be right – relaxing will only help a tad… While keenly aware of the high prices many are willing to pay, Cort does not seem to grasp the incredible degree to which development is inhibited by zoning. “Relaxing” won’t do the trick in a city where prices are high enough to justify skyscrapers with four to ten times the density currently allowed. When considering a supply cap that only allows a fraction of what the market demands, one can not reasonably conclude “Unlimited FAR” (building density) would merely result in a bit more development here and there. A radically liberalized land-use regime would […]

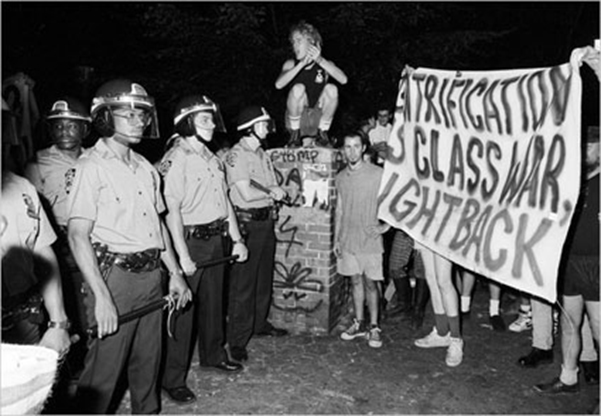

Gentrification is the result of powerful economic forces. Those who misunderstand the nature of the economic forces at play, risk misdirecting those forces. Misdirection can exasperate city-wide displacement. Before discussing solutions to fighting gentrification, it is important to accept that gentrification is one symptom of a larger problem. Anti-capitalists often portray gentrification as class war. Often, they paint the archetypal greedy developer as the culprit. As asserted in jacobin magazine: Gentrification has always been a top-down affair, not a spontaneous hipster influx, orchestrated by the real estate developers and investors who pull the strings of city policy, with individual home-buyers deployed in mopping up operations. Is Gentrification a Class War? In a way, yes. But the typical class analysis mistakes the symptom for the cause. The finger gets pointed at the wrong rich people. There is no grand conspiracy concocted by real estate developers, though it’s not surprising it seems that way. Real estate developers would be happy to build in already expensive neighborhoods. Here, demand is stable and predictable. They don’t for a simple reason: they are not allowed to. Take Chicago’s Lincoln Park for example. Daniel Hertz points out that the number of housing units in Lincoln Park actually decreased 4.1% since 2000. The neighborhood hasn’t allowed a single unit of affordable housing to be developed in 35 years. The affluent residents of Lincoln Park like their neighborhood the way it is, and have the political clout to keep it that way. Given that development projects are blocked in upper class neighborhoods, developers seek out alternatives. Here’s where “pulling the strings” is a viable strategy for developers. Politicians are far more willing to upzone working class neighborhoods. These communities are far less influential and have far fewer resources with which to fight back. Rich, entitled, white areas get down-zoned. Less-affluent, disempowered, minority […]

Co-authored with Anthony Ling, editor at Caos Planejado Gentrification Gentrification is the process through which real estate becomes more valuable and, therefore, more expensive. Rising prices displace older residents in favor of transplants with higher incomes. This shouldn’t be confused with the forced removal of citizens via eminent domain or “slum clearance.” Ejecting residents by official fiat is a different problem entirely. A classic example of gentrification is that of Greenwich Village, New York. Affluent residents initially occupied the neighborhood. It later became the city’s center for prostitution, prompting an upper-middle class exodus. Low prices and good location would later attract the textile industry. This was the neighborhood’s first wave of gentrification. But after a large factory fire, the neighborhood was once again abandoned. Failure, however, would give way to unexpected success: artists and galleries began to occupy the vacant factories. These old industrial spaces soon became home to one of the most important movements in modern art. In Greenwich Village, different populations came and went. And in the process they each made lasting contributions to New York’s economic and cultural heritage. This was only possible because change was allowed to take place. But change isn’t always easy. As a neighborhood becomes more popular, it also becomes more expensive. Tensions run high when long-time residents can’t afford rising rents. Some begin to call for rent controls or other measures to prevent demographic churn. But rent control is a temporary fix at best; in the longer term, its effects are negative. By reducing supply, rent control tends to drive up the cost of housing. And in the face of price controls, landlords may seek to exit the rental market entirely, further exacerbating any housing shortage. What, then, does this mean for urban development? How can cities evolve without completely displacing their middle and […]

Want to live in San Francisco? No problem, that’ll be $3,000 (a month)–but only if you act fast. In the last two years, the the cost of housing in San Francisco has increased 47% and shows no signs of stopping. Longtime residents find themselves priced out of town, the most vulnerable of whom end up as far away as Stockton. Some blame techie transplants. After all, every new arrival drives up the rent that much more. And many tech workers command wages that are well above the non-tech average. But labelling the problem a zero sum class struggle is both inaccurate and unproductive. The real problem is an emasculated housing market unable to absorb the new arrivals without shedding older residents. The only solution is to take supply off its leash and finally let it chase after demand. Strangling Supply From 2010 to 2013, San Francisco’s population increased by 32,000 residents. For the same period of time, the city’s housing stock increased by roughly 4,500 units. Why isn’t growth in housing keeping pace with growth in population? It’s not allowed to. San Francisco uses what’s known as discretionary permitting. Even if a project meets all the relevant land use regulations, the Permitting Department can mandate modifications “in the public interest”. There’s also a six month review process during which neighbors can contest the permit based on an entitlement or environmental concern. Neighbors can also file a CEQA lawsuit in state court or even put a project on the ballot for an up or down vote. This process is heavily weighted against new construction. It limits how quickly the housing stock can grow. And as a result, when demand skyrockets so do prices. To remedy this, San Francisco should move from discretionary to as-of-right permitting. In an as-of-right system, it’s much […]

Affordable housing policies have a long history of hurting the very people they are said to help. Past decades’ practices of building Corbusian public housing that concentrates low-income people in environments that support crime or pursuing “slum clearance” to eliminate housing deemed to be substandard have largely been abandoned by housing affordability advocates for the obvious harm that they cause stated beneficiaries. While rent control remains an important feature of the housing market in New York and San Francisco, even Bill de Blasio’s deputy mayor acknowledges the negative consequences of strong rent control policies. In the U.S. and abroad, politicians and pundits are beginning to vocalize the fact that maintaining and improving housing affordability requires housing supply to increase in response to demand increases. While support for older housing affordability policies has dissipated, the same isn’t true of inclusionary zoning. From New York to California, housing affordability advocates tout IZ as a cornerstone of successful housing policy. IZ has emerged as the affordable housing policy of choice because it has the benefit of supporting socioeconomic diversity, and its costs are opaque and dispersed over many people. However, IZ has several key downsides including these hidden costs and a failure to meaningfully address housing affordability for a significant number of people. Shaila Dewan of the New York Times captures the strangeness of IZ’s popularity: New York needs more than 300,000 units by 2030. By contrast, inclusionary zoning, a celebrated policy solution that requires developers to set aside units for working and low-income families, has created a measly 2,800 affordable apartments in New York since 2005. Montgomery County, a Maryland suburb of DC, has perhaps the most well-established IZ policy in the country. After 30 years, the program has produced about 13,000 units. Montgomery County is home to over one million people, 20 percent of whom have a household income of less than $43,000 annually. While this is an extraordinarily high income distribution relative to the rest of the country, this makes the […]

Stephen Smith and I co-wrote this post. In case you haven’t been following Stephen elsewhere, he’s also been writing at The Atlantic Cities and Bloomberg View. This year, some of the first apartments and condos subject to inclusionary zoning laws in DC are hitting the market, stoking debate over development laws that the city adopted in 2007. The inclusionary zoning requirement is currently stalling the city’s West End Library renovation with Ralph Nader leading efforts to include an affordable housing aspect with the library project. Inclusionary zoning advocates often base their support on the desirability of mixed-income neighborhoods, while challengers argue that inclusionary zoning is an inefficient way to deliver housing with unintended consequences. Heather Schwartz, who studies education and housing policies at the RAND Institute, says that one important feature of this policy tool is that it gives low-income families access to high-income neighborhoods while at the same time limiting the number of low-income residents in a neighborhood. She said, “Since IZ is a place-based strategy that tends to only apply to high-cost housing markets, it can offer access to lower-poverty places than housing vouchers and other forms of subsidized housing have historically done.” David Alpert, editor-in-chief of Greater Greater Washington, a local urban planning blog, offers another argument in favor of inclusionary zoning, “a policy that builds support for both greater density and affordable housing,” he said in an email. “Much of the opposition to greater density involves a feeling that it is just a ‘giveaway’ to developers who make the profit and impose some collateral burden on a neighborhood, but many people are more supportive of the density if it serves an affordable housing goal.” While inclusionary zoning proponents may see its ability to introduce just a few low-income residents to a higher income neighborhood as an […]

At Next American City, Mark Bergen has an interesting long-form piece on municipal infrastructure financing. He argues that the property owners who benefit from public policies, such as infrastructure investment, should be required to fund these policies. He suggests infrastructure improvements should be paid for with Tax Increment Finance or value capture (PDF). I don’t necessarily agree with his infrastructure funding prescriptions, and may take these up in a future post. What I found even more interesting, though, is his suggestion that developers should pay for zoning changes. The basis for this proposal comes from the Georgist land tax. Because in urban settings, land’s value largely comes from the amenities surrounding it, landowners do not have the exclusive rights to this value, according to Henry George. The suggestion that developers should pay for the rights to build on the land they own is based, Mark explains, on a policy from São Paulo, called Certificates of Additional Construction Potential (CEPAC). These bonds, representing rights to build, are transferable and are publicly traded. He quotes Gregory K. Ingram of Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: “They’re essentially selling zoning changes,” explained Ingram. Crucially, the building fees have not eaten away at developers’ profits. By some accounts, the rates of return for real estate in the districts increase. […] The notes, sold by municipalities, are one of the world’s most innovative public financing techniques. Across many sections of São Paulo, if a developer hopes to build or do nearly anything with her property — adjust its uses, expand outward or upward — she must first buy a CEPAC. On a fairness level, selling zoning changes seems wrong to me. Current zoning policies are an arbitrary starting point, so it doesn’t make sense that developers should have to pay for permission to change a policy that […]

The debate you’ve been waiting for! Randal O’Toole, Matt Yglesias, Ryan Avent, and Adam Gordon participated yesterday in a discussion at the Cato Institute moderated by Diana Lind from Next American City/Forefront. (How had this never happened before??) Randal O’Toole did not disappoint, arriving in top form in his shoestring necktie and armed with a surprisingly interesting Powerpoint, but I think New Jersey-based attorney Adam Gordon stole the show with his discussion of inclusionary zoning and the Mt. Laurel doctrine (probably because he was on the only one on stage who hasn’t already spewed hundreds of thousands of words on the subject). You can download the 90-minute discussion as an MP3 from Cato (much easier to scroll through), or watch the video streaming:

California Assembly Bill 710 was introduced to earlier this year to tackle the problem of municipalities requiring onerous amounts of parking for new development, widely recognized as one of the main impediments to transit-oriented development and infill growth. The bill would have capped city and county parking requirements in neighborhoods with good transit to one space per residential unit and one space per 1,000 sq. ft. of non-residential space, with an exemption process for areas with a true parking crunch and some other caveats….