Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

1. Recently at Market Urbanism: Two Cheers for PHIMBY by Michael Lewyn One alternative to market urbanism that has received a decent amount of press coverage is the PHIMBY (Public Housing In My Back Yard) movement. PHIMBYs (or at least the most extreme PHIMBYs) believe that market-rate housing fails to reduce housing costs and may even lead to gentrification and displacement. Their alternative is to build massive amounts of public housing. New and Noteworthy: Randy Shaw’s Generation Priced Out by Michael Lewyn In Generation Priced Out, housing activist Randy Shaw writes a book about the rent crisis for non-experts. Shaw’s point of view is that of a left-wing YIMBY: that is, he favors allowing lots of new market-rate housing, but also favors a variety of less market-oriented policies to prevent displacement of low-income renters (such as rent control, and more generally policies that make it difficult to evict tenants) “Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities” Out Today by Nolan Gray Alain Bertaud’s long awaited book, Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, is out today. Bertaud is a senior research scholar at the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management and former principle urban planner at the World Bank. “Order Without Design”, a new guide to urban planning by Anthony Ling This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding. This is how Jane Jacobs opened her 1961 classic “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”. It wouldn’t be an inappropriate opener for Alain Bertaud’s upcoming “Order Without Design”. 2. Also by Market Urbanists: Nolan Gray‘s viral tweet critiquing local control of land use: Local control is America’s weirdest fetish. Every single one of these photos shows a room full of people—in no way representative of their respective communities—agitating against affordable, multifamily, and/or mixed-use housing. Every single one was taken in 2018. pic.twitter.com/4bW2aDwPDI — Nolan Gray (@mnolangray) December 2, […]

This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding. This is how Jane Jacobs opened her 1961 classic “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”. It wouldn’t be an inappropriate opener for Alain Bertaud’s upcoming “Order Without Design”. While Jacobs was an observer of how cities work and a contributor to new concepts in urban economics, Bertaud goes a step further. His book brings economic logic and quantitative analysis to guide urban planning decision-making, colored by a hands-on, 55-year career as a global urban planner. His conclusion? The urban planning practice is oblivious to the economic effects of their decisions, and eventually creates unintended consequences to urban development. His goal with this book is to bring economics as an important tool to the urban planning profession, and to bring economists closer to the practical challenge of working with cities. Maybe you have not heard about Alain Bertaud before: at the time I am writing this article, he has only a few articles published online, no Wikipedia page or Twitter account, and some lectures on YouTube – and nothing close to a TED talk. The reason is that instead of working on becoming a public figure, Bertaud was actually doing work on the ground, helping cities in all continents tackle their urban development problems. His tremendous experience makes this book that delves into urban economics surprisingly exhilarating. As an example, Bertaud shows a 1970 photo from when he was tracing new streets in Yemen using a Land Rover and the help of two local assistants who look 12 years old at most, a depiction of a real-life Indiana Jones of urban planning. In this book, mainstream urban planning “buzzwords” such as Transit-Oriented Development, Inclusionary Zoning, Smart Growth and Urban Growth Boundaries are challenged with economic analysis, grounded on […]

Alain Bertaud’s long awaited book, Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, is out today. Bertaud is a senior research scholar at the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management and former principle urban planner at the World Bank. Working through a pre-release copy over the past few weeks, I can confidently say that the book is an instant classic of the urban planning genre, and will be of significant special interest to market urbanists in particular. Rare among writers in this space, Bertaud brings an architect’s eye, an economist’s mind, and a planner’s experience to contemporary urban issues, producing a text that is theoretically enriching and practically useful. Alain and Marie-Agnes—his wife and research partner—have lived in worked in over a half-dozen cities all over the world, from Sana’a to Paris to San Salvador to Bangkok. For the reader, this means that Bertaud can speak from experience, supplementing data and theory with entertaining, real world examples and war stories. Order your copy today!

In Generation Priced Out, housing activist Randy Shaw writes a book about the rent crisis for non-experts. Shaw’s point of view is that of a left-wing YIMBY: that is, he favors allowing lots of new market-rate housing, but also favors a variety of less market-oriented policies to prevent displacement of low-income renters (such as rent control, and more generally policies that make it difficult to evict tenants). What I liked most about this breezy, easy-to-read book is that it rebuts a wide variety of anti-housing arguments. For example, NIMBYs sometimes argue that new housing displaces affordable older housing. But Shaw shows that NIMBY homeowners oppose apartment buildings even when this is not the case; apartments built on parking lots and vacant lots are often controversial. For example, in Venice, California, NIMBYs opposed “building 136 supportive housing units for low-income people on an unsightly city-owned parking lot.” NIMBYs may argue that new housing will always be for the rich. But Shaw cites numerous examples of NIMBYs opposing public housing for the poor as well as market-rate housing for the middle and upper classes. NIMBYs also claim that they seek to protect their communities should be protected against skyscrapers or other unusually large buildings. But Shaw shows that NIMBYs have fought even the smallest apartment buildings. For example, in Berkeley, NIMBYs persuaded the city to reject a developer’s plan to add only three houses to a lot. On the other hand, market urbanists may disagree with Shaw’s advocacy of a wide variety of policies that he refers to as “tenant protections” such as rent control, inclusionary zoning, increased code enforcement, and generally making it difficult to evict tenants. All of these policies make it more difficult and/or expensive to be a landlord, thus creating costs that may either be passed on to tenants […]

One alternative to market urbanism that has received a decent amount of press coverage is the PHIMBY (Public Housing In My Back Yard) movement. PHIMBYs (or at least the most extreme PHIMBYs) believe that market-rate housing fails to reduce housing costs and may even lead to gentrification and displacement. Their alternative is to build massive amounts of public housing. On the positive side, PHIMBYism, if implemented, would increase the housing supply and lower housing costs, especially for the poor who would be served by new public housing. And because there is certainly ample consumer demand for new housing, PHIMBYism would be more responsive to consumer preferences than the zoning status quo (which privileges the interests of owners of existing homes over those of renters and would-be future homeowners). But PHIMBYism is even more politically impossible than market urbanism. Market urbanists just want to eliminate zoning codes that prevent new housing from being built- a heavy lift in the political environment of recent decades. But PHIMBYs want to override the same zoning codes, AND find the land for new public housing (which often will require liberal use of eminent domain by local governments), AND find the taxpayer money to build that new public housing, AND find the taxpayer money to maintain that housing forever. And to make matters worse, the old leftist remedy of raising taxes on the rich might be inadequate to fund enough housing, because the same progressives who are willing to spend more money on housing also want to spend more public money on a wide variety of other priorities, thus making it difficult to find the money for housing.

1. Recently at Market Urbanism: Three Policies for Making Driverless Cars Work for Cities by Emily Hamilton To avoid repeating mistakes of the past, policymakers should create rules that neither subsidize AVs nor give them carte blanche over government-owned rights-of-way. Multiple writers have pointed out that city policymakers should actively be designing policy for the driverless future, but few have spelled out concrete plans for successful driverless policy in cities. Here are three policies that urban policymakers should begin experimenting with right away in anticipation of AVs. Rent Control Makes It Harder to Vote with Your Feet by Gary Galles devolving political power to lower level governments does not serve citizens’ rights when it comes to rent control, because rent control paralyzes owners’ ability to escape imposed burdens by voting with their feet. 2. Also by Market Urbanism writers: Nolan Gray at Citylab: Voters Said No in California, but Other States Have Rent Control Battles Looming Michael Lewyn at Planetizen: The Lincoln Park Story (On Daniel Hertz new book on the gentrification of the Chicago neighborhood) Michael Lewyn at Planetizen: New Urbanists and New Housing (about the friendly-but-troubled Market Urbanist/New Urbanist relationship) 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Roger Valdez for Forbes: How To End The ‘Housing Crisis’ Roger Valdez for Forbes: HQ2 Frontlash Begins: The Answer Is More Housing, Some Built By Amazon Isabella Chu asks: Are people equally concerned about how to bring jobs to the once flourishing and housing rich older cities of the northeast? Anthony Ling asks: What are your thoughts on Richard Florida’s petition against Amazon HQ2’s “auction”? Via Joe Wolf: Seattle’s Most Influential People 2018: The YIMBYs Via Mirza Ahmed: Paid parking could be coming to Tacoma Dome Station Via Elizabeth Connor: Why we should pay more for parking Via Robert Wilson: At “Eleventh Hour,” City Rejects Tiny Home Village Plan to Relocate to TAXI Campus Via […]

One advantage of a federal system is enabling people ill-treated by one government body to “vote with their feet” toward less abusive jurisdictions. That escape valve is one rationale for reserving some political policy determination for state rather than national government, or to local rather than state government. However, devolving political power to lower level governments does not serve citizens’ rights when it comes to rent control, because rent control paralyzes owners’ ability to escape imposed burdens by voting with their feet. Virtually every rent control story focuses on local government policies. Less well known, however, is that a majority of states actually ban or restrict local governments’ power to impose rent control. And currently, in at least four states (California, Oregon, Washington, and Illinois), those restrictions are under attack. Municipalities want power they are currently denied so they can impose rent control, supposedly to give local citizens “what they want.” That raises the question of whether rent control policy should be vested at the state level or the local level. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Local Governance In many circumstances, the option to vote with your feet favors local governance. It is generally less costly to leave a small local government jurisdiction whose benefits are not worth the cost, than it is to leave a similarly bad state government jurisdiction. By the same token, it is less costly to leave a state than it is to leave the country. The enhanced exit options provided at a more local level may better protect citizens’ rights. Citizens’ ability to cheaply leave smaller jurisdictions more tightly limits government’s ability to use them as cash cows rather than serve them better. This is true of sales and income taxes, for example. Dissatisfied residents can avoid those burdens by going somewhere […]

Some urbanists have become skeptical about the future of autonomous vehicles even as unstaffed, autonomous taxis are now serving customers in Phoenix and Japan. Others worry that AVs, if they are ever deployed widely, will make cities worse. Angie Schmitt posits that allowing AVs in cities without implementing deliberate pro-urban policies first will exacerbate the problems of cars in urban areas. However, cars themselves aren’t to blame for the problems they’ve caused in cities. Policymakers created rules that dedicated public space to cars and prioritized ease of driving over other important goals. Urbanists should be optimistic about the arrival of AVs because urbanist policy goals will be more politically tenable when humans are not behind the wheel. To avoid repeating mistakes of the past, policymakers should create rules that neither subsidize AVs nor give them carte blanche over government-owned rights-of-way. Multiple writers have pointed out that city policymakers should actively be designing policy for the driverless future, but few have spelled out concrete plans for successful driverless policy in cities. Here are three policies that urban policymakers should begin experimenting with right away in anticipation of AVs. Price Roadways Perhaps the biggest concern AVs present for urbanists is that they may increase demand for sprawl. AVs may drastically reduce highway commute times over a given distance through platooning, and if people find their trips in AVs to be time well-spent, when they can work, relax, or sleep, they may be willing to accept even more time-consuming commutes than they do today. As the burden of commuting decreases, they reason, people will travel farther to work. However, the looming increase in sprawl would be due in large part to subsidized roads, not AVs themselves. If riders would have to fully internalize the cost of using road space, they would think twice […]

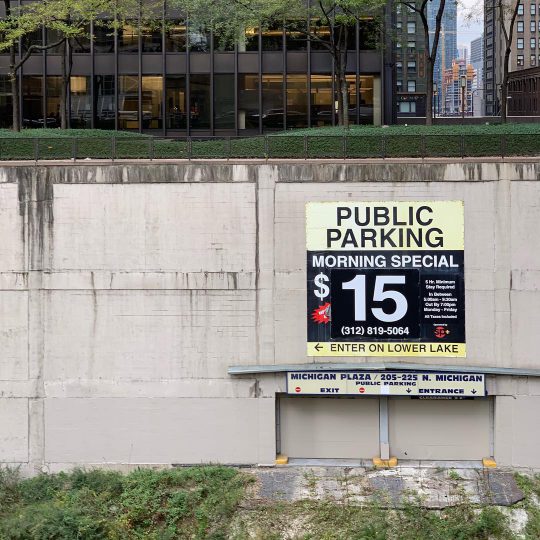

1. Recently at Market Urbanism: Response to “Steelmanning the NIMBYs” by Michael Lewyn Scott Alexander, a West Coast blogger, has written a post that has received a lot of buzz, called “Steelmanning the NIMBYs”; apparently, “steelmanning” is the opposite of “straw manning”; that is, it involves making the best possible case for an argument you don’t really support. The land price argument and why it fails by Michael Lewyn One common argument against all forms of infill development runs something like this: “In dense, urban areas land prices are always high, so housing prices will never be affordable absent government subsidy or extremely low demand. 2. Also by Market Urbanism writers: Nolan Gray at Strong Towns: Wide Streets as a Tool of Oppression Nolan Gray at CityLab: The Improbable High-Rises of Pyongyang, North Korea Nolan Gray at Strong Towns: What if Lexington Got Serious About Student Drunk Driving? 3. At the Market Urbanism Facebook Group: Randy Shaw launched pre-orders for his upcoming book, Generation Priced Out: Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America Donald Shoup for Planning Magazine: Parking Price Therapy Nolan Gray shares the campaign site for a YIMBY candidate, Sonja Trauss for Supervisor 2018 Matt Miller asks: What’s the future of retail? Mark D Fulwiler says: Only about 4% of all commuters ( on average ) take mass transit on any given day Ben Barov asks: Are vacancy taxes market urbanism? Andrew Mayer asks: How much urban housing needs to be built to fix the deficit of supply? James Hanley likes open space on waterfronts, but keeps thinking of Jane Jacobs‘ criticisms of big parks. “What are your responses to this?” Via Adam Hengels: Steelmanning the NIMBYs Via Shawn Ruest: Elizabeth Warren’s New Bill Would Spend $500 Billion on Housing Via Carl Webb: So You Want to Change Zoning to Allow for More Housing Via Stephen Bone: How Singapore Solved Its Housing Problem Via Michael Burns: A Network […]

One common argument against all forms of infill development runs something like this: “In dense, urban areas land prices are always high, so housing prices will never be affordable absent government subsidy or extremely low demand. Furthermore, laws that allow new housing will make land prices even higher, thus making housing more unaffordable.” This argument seems to be based on the assumption that land prices are essentially a fixed cost: that is to say, that they can only go up, never go down. In fact, land costs are extremely volatile. For example, a recent Philadelphia Inquirer story showed that in Philadelphia, land costs per square foot of vacant land fell by 46 percent over the last year. Why? A developer quoted in the story suggests that as supply has started to keep up with demand, rents have declined, causing land prices to decline. In other words, when supply increases, rents go down AND so do land prices.