Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Since 1973, the US Census Bureau has administered the American Housing Survey (AHS) in odd-numbered years. Surveyors ask questions about the quality and value of respondents’ housing, and have a battery of questions for the subset of respondents who moved recently, asking about their search process. The AHS regularly adds new questions and rephrases old ones from year to year. In 2021, they rolled out a group of three new questions. One asks recent movers whether they spent more or less than a month searching for their new home. This is the AHS’s first-ever variable dealing with search time. The other two, which are similar to questions asked in previous years, ask about search scope: whether respondents looked for housing in neighborhoods besides the one they ended up moving to, and whether they looked at other housing units in the same neighborhood they moved to. In analyzing these new questions within the largest 15 metro areas in the US, I found a curious and hard-to-explain relationship. Search time – the binary variable of taking more or less than a month to look for a home – seems to be predicted by the population of a metropolitan area (with r=0.57 and p > |t| = 0.026), whereas search scope in the sense of looking at multiple neighborhoods or multiple units within a neighborhood seems to be predicted by the cost of housing as gathered from 2021 Zillow data (for looking at multiple neighborhoods, r=0.65 and p > |t| = 0.009; for looking at multiple units, r=0.68 and p > |t| = 0.007). The inverse set of relationships are much weaker. Price and likelihood of taking over a month to search are positively correlated, but the relationship is not statistically significant; the same is true of the relationship between metro population and […]

Update 11/20: Chang-Tai Hsieh counters that Greaney’s critique ignores general equilibrium effects which make labor scale invariant. That doesn’t address the alleged coding errors. We’ll see – and perhaps I wrote an autopsy too early. Thanks to Bryan Caplan for getting Hsieh’s response out to the world. Popular urban econ should be shaken with the revelation that its most famous academic paper had two coding errors, a serious theoretical flaw, and a hypothesized mechanism that – when executed correctly – did not work at all. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti’s paper Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation noted that “high productivity cities like New York and the San Francisco Bay Area have adopted stringent restrictions to new housing supply, effectively limiting the number of workers who have access to such high productivity” – and used a simple model to estimate how much US growth could have been unlocked by decreasing those restrictions. Brian Greaney, an assistant professor at the University of Washington, released notes on his replication of The paper gained widespread notice as a 2015 NBER working paper and was published in 2019 in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. The paper already has an impressive 813 scholarly citations. But the paper has problems – fatal problems – and is embarrassingly sloppy. The embarrassment extends beyond the authors to the many referees and editors who missed surface, implementation, architectural, and foundational problems over a four-year period of peer review and discussion. Surface Greaney is not the first to find a mistake in Hsieh & Moretti. Bryan Caplan caught a major inconsistency in 2021, one that readers (myself included) and referees should have caught earlier. The authors reported huge annual effects adding up to a merely-large effects over 45 years. He noted a few other arithmetical mistakes and generously concluded, “authors and referees […]

By Andrew Crouch and Charles Gardner In March 2023, Arlington County, Virginia passed an amendment to its zoning ordinance which legalized so-called “missing middle” housing typologies in several residential districts, including many which had been zoned for single-family homes. Ten local homeowners filed suit in Arlington County Circuit Court in April 2023, alleging among other things that the proper procedure for amending the ordinance was not followed and the zoning change should be invalidated. The County Board and Planning Commission, the defendants in the lawsuit, fired back, alleging a fatal lack of standing and claims that, if they were true, could not and should not be resolved by the circuit court. During proceedings held on October 19, 2023, Judge David Schell delivered a win to the plaintiffs, ruling that they have demonstrated standing by virtue of being within the rezoned area and that the case against Arlington County’s missing middle zoning ordinance amendment therefore may proceed to trial. Initial trial proceedings are scheduled for November 16, 2023. Judge Schell also ruled in favor of the defendants on a separate issue, holding that one of the plaintiffs’ seven claims, alleging a violation of the Virginia Freedom of Information Act (VFOIA), should be dismissed. With respect to standing, Judge Schell ruled that the claims made by the homeowners, if true and presented in the most favorable light, were justiciable and ripe for relief, and that the homeowners had standing to challenge a general zoning ordinance. The latter holding may set precedent, as the cases presented to the court by the parties did not address the issue of standing in the context of an ordinance-level, district-wide zoning change. In their 162-page complaint, plaintiffs claim entitlement to sue on the basis that the ordinance “will result in a higher tax assessment,” although this appears […]

Tyler is stirring the pot over at Marginal Revolution, asking whether Tokyo’s low rents are a YIMBY success or just a productivity failure: low productivity and low immigration keep demand down. He calls the latter “NIMBYism”. That framing doesn’t hold up very well, but we can discard it and think about the substance of the question. If we were totally ignorant of policy, what would we expect? Alonso-Muth-Mills models say prices should be higher in larger cities, and Tokyo is the largest city in the world. Most people think that price/income is the right way to compare home prices across countries, although price/construction cost might be better if we could accurately measure the latter. Let’s at least clarify the factual issues. Are Tokyo wages low? Japan wages are quite low by developed-world standards. Tokyo is perhaps 22% above the national average, about half of the New York/USA markup. The Alonso-Muth-Mills model says the largest city should be so because its wages are highest. Obviously, that assumes free movement of people. It’s not a mystery why Karachi is larger than Austin. But then why is Tyler criticizing Japan for low immigration? Clearly Japanese people should emigrate, like wage peer Spaniards and Poles. Is Tokyo cheap? Only relatively. I asked ChatGPT for a comparative list, but it wouldn’t even try. The best comparison I could find was in Demographia’s affordability yearbooks. They last included Japan in 2018 because of data reliability issues, so ymmv. But a Japanese PDFsays that Metropolitan Tokyo’s price-income ratio was 7.16 in 2016; in Tokyo Prefecture (the core) it was 9. Who knows how the definitions differ? All sources agree that Japanese home prices have risen less than most of the world in the pandemic era, so current data would favor Tokyo more. Tyler’s claim that Japan’s “brand […]

In a recent report from the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, Chris Denson and J. Thomas Perdue compile the strictest minimum lot size regulations and minimum home size regulations from a range of cities and counties in Georgia. 31 of Georgia’s 159 counties mandate minimum lot sizes (in unincorporated land, on some districts) larger than 1 acre, with minimums as high as 5 acres in two southwestern Georgia counties. Charting local zoning in America is no small task, and Denson and Perdue give a valuable snapshot of one of its facets in a big and growing state. Georgia is not known for onerous regulation of homebuilding – when I volunteered with Abundant Housing LA, a fellow volunteer who’d moved from Georgia would shame liberal NIMBYs by saying how much easier it was to get apartments permitted in her conservative home state – but like much of the US, Georgia’s home construction has failed to meet the growing demand. Denson and Perdue spotlight one specific regulatory tool more typical of Georgia than elsewhere: minimum home size regulations (as distinct from minimum lot size regulations, which are ubiquitous nationwide). Denson and Perdue show that Georgia counties and county seats often require minimum home sizes far in excess of American Society of Planning Officials benchmarks, and point out this drives up housing costs significantly. Below is a map (made in ArcGIS by my colleague Micah Perry) of Denson and Perdue’s data on county government minimum home sizes, showing the highest minimum in any zone on unincorporated land for counties for which data was available: The clear lesson from Georgia’s surprisingly strict regulations is that policymakers in growing Sun Belt cities and states shouldn’t delude themselves: the crises afflicting coastal “superstar” cities are coming for them too if they don’t liberalize land use laws. Austin […]

One common NIMBY argument is that new development is bad because it brings traffic. As I have pointed out elsewhere, this is silly because it is a “beggar thy neighbor” argument: the traffic doesn’t go away if you block the development, it just goes somewhere else. But my argument assumed that new development would in fact bring traffic wherever it occurred. A new study by three North Carolina State University scholars suggests otherwise. The study concludes that “rural locations are more likely to experience an increase in traffic due to increased development as compared to urban land uses.” (p. 19). This is because “locations that did not experience a significant traffic increase… had a higher traffic volume before development”. (p. 20). This might be because those areas were “already highly saturated, which served as a major disincentive for the migration of traffic” (id.) So in other words, if I am understanding this paper correctly, an already-congested area will not get much more congested with new development, because people react to congestion by going elsewhere or using slightly different routes. By contrast, when a basically uncongested area gets new development, the new development does not create enough traffic to scare off drivers.

A study by Maxim Massenkoff and Nathan Wilmers argues that “low-price full-service restaurants,” like Olive Garden or the Cheesecake Factory, are the third places in which rich and poor are most likely to rub shoulders. Using location data, they found that these low-price chain restaurants had more class integration than churches, schools, and independent bars and restaurants. Although Massenkoff and Wilmers steer clear of making forceful policy recommendations, they do seem to caution policymakers in cities like San Francisco and New York City that have passed regulations to curb an overabundance of chains: Our results demonstrate that the places that contribute most to mixing by economic class are not civic spaces like churches or schools, but large, affordable chain restaurants and stores. Insofar as policy makers seek to increase exposure between different classes, they should pay attention to the role of firms in shaping class mixing. It is not necessarily surprising that chain restaurants tend to be places where people of all classes mix. The very design of these restaurants is meant to appeal to the widest audience possible. Behold your local Cheesecake Factory. It is usually found in suburban shopping centers where land is cheap, such that the Factories are large and capable of holding all large numbers of customers. And of course, The Factory’s famously tome-like menu, which has everything from hamburgers to orange chicken to shrimp scampi, betrays the chain’s intention to serve as many different walks of life as possible. But it is also worth considering that chains, even if they are designed to appeal to the largest audience possible, might be playing an outsized role in class integration. Research from City Observatory argues that chains tend to proliferate in more car-dependent cities. It is not entirely obvious why this is the case, but some theories […]

I’ve noticed numerous stories and tweets about a building boom: for example, a recent CNBC story asserts that the number of new apartments is “at a 50-year high.” Various twitterati have used this claim to support their own points of view: some claim that rents are stabilizing because of this new surge in supply, while others argue that the failure of rents to decline shows that new supply doesn’t reduce rents. But is supply really increasing that rapidly? Federal statistics on housing construction are at a Census housing data webpage. I looked at the “New Housing Units Completed” table and found that about 216,000 housing units in structures with over five units were completed in the first half of 2023. On the positive side, this is definitely an improvement over the 2010s, when the economy was still recovering from the 2008 recession. For example, in the first half of 2019, just over 169,000 such units were built, and 2018 was pretty similar. But is construction still up to Reagan-era levels? Not really. In the first half of 1986, almost 258,000 relevant units were completed. And in the first half of 1973, just over 378,000(!) such units were built. And these levels of construction were in a less populous country. Today the U.S. population is about 335 million, up from about 240 million in 1986 and 212 million in 1973. So if construction had kept up with population, our new unit count would be about 1/3 higher than in 1986, and almost 60 percent higher than in 1973. Instead, construction went down. To put the facts another way: our half-year multifamily construction rate is about 644 per one million Americans for 2023, down from 1075 per million in 1986 and 1783 per million in 1973. That’s not my idea of a […]

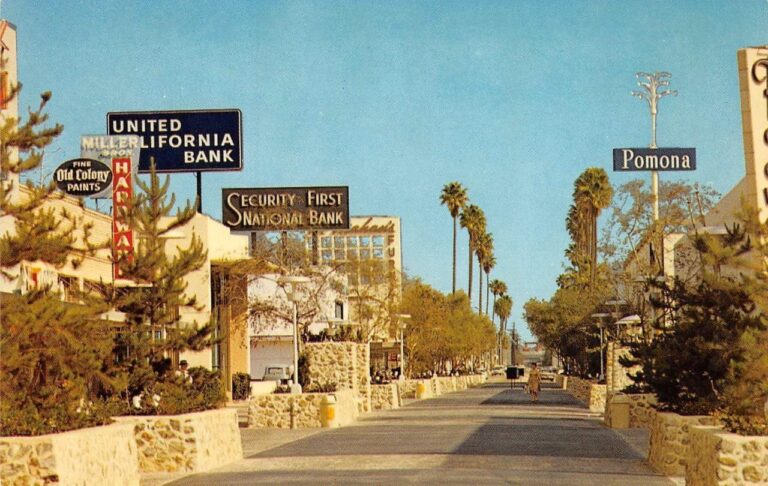

Urbanists love to celebrate, and replicate great urban spaces – and sometimes can’t understand why governments don’t: But what’s important to recall – especially for those of us under, uh, 41 – is that pedestrianized streets aren’t a new concept coming into style, they’re an old one that’s been in a three-decade decline. Samantha Matuke, Stephan Schmidt, and Wenzheng Li tracked the rise and decline of the pedestrian mall up to the onset of the pandemic. Even in the urbanizing 2000s and 2010s, 14 pedestrian malls were “demalled” against 4 streets that were pedestrianized: In a 1977 handbook promoting pedestrianization, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo admit that some of the earliest “successes” had already failed: In Pomona, California, the first year [1962] the mall received nationwide press coverage as a successful model of urban revitalization; there was a 40 percent increase in sales. But the mall was slowly abandoned by its patrons, and now, after fifteen years of operation, it is almost totally deserted. A Handbook for Pedestrian Action, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo, p. 25 One obvious reason for the failure of many other pedestrianized streets is that they were too little, too late. The pedestrian mall was one of several strategies against the overwhelming ebb tide of retail from downtowns in the postwar era. They weren’t seen as alternatives to driving, but destinations for drivers, who could park in the new, convenient downtown lots that replaced dangerous, defunct factories. A minority of the postwar-era malls survived. The predictors of survival are sort of obvious in hindsight: tourism, sunny weather, and lots of college students, among other things. Some of the streets which were “malled” and “demalled” have rebounded nicely in the 2000s. The slideshow below shows Sioux Falls’ Phillips Avenue in 1905, 1934, c. 1975, and 2015. The […]

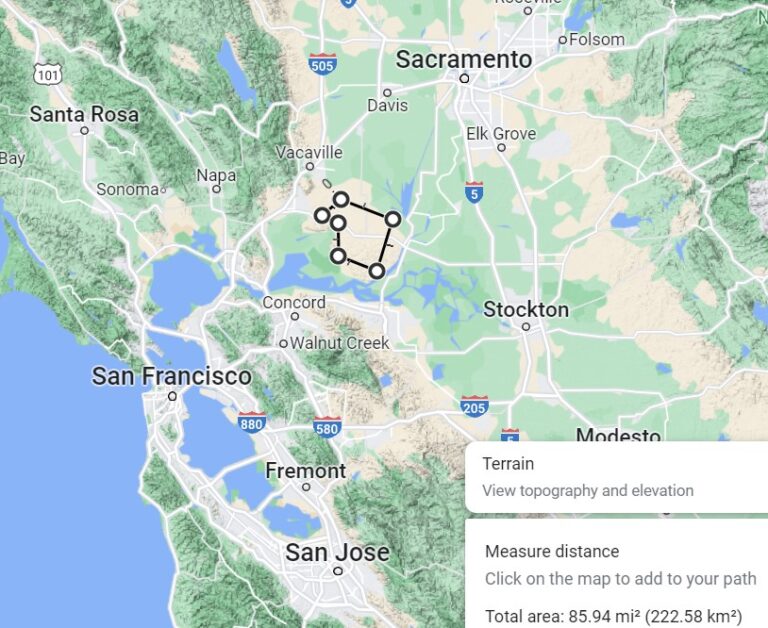

Conor Dougherty and Erin Griffith revealed the identities behind a Silicon Valley investor group, Flannery Associates, that had gradually purchased 55,000 acres of ranchland near Travis Air Force Base in Solano County, California. Scale check: that’s a lot of land. San Francisco is 30,000 acres; San Jose is 116,000. Earlier WSJ reporting includes a map of Flannery’s holdings, which are predictably a bit scattered. To zoom out and give a scale comparison, I outlined a 55,000 acre contiguous blob around the core of the Flannery holdings. At the density of nearby Vacaville, this much land would be home to nearly 300,000 people. If it matched Oakland, it would be more than twice that. Many, especially at the Charter Cities Institute, have written about new cities. But can a new city ever be truly “market urbanist”? Or is the intent to create a city necessarily an exercise in centralized planning? Monopoly Bizarrely, the one actor who could most purely create a market-driven city is the government: It could use eminent domain to assemble only the land needed for new infrastructure, tax all landowners fairly, and allow competition among landowners to compete via development and land use. At the opposite extreme, when a profit-maximizing private actor owns all the land, it faces a unique form of the monopolist’s tradeoff: The longer it holds onto land, the higher price it can charge on sale, but the less that land contributes to urban growth. One way to sidestep this tradeoff is for the monopolist to develop land itself. But of course that concentrates risk, and the cost of development is at least a hundred times more than the land cost (which appears to have averaged about $16,000 per acre in Solano County). Zero to one So what’s a mega-landowner to do? I’d start by […]