The post No Solutions, Just Tradeoffs appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>We provide evidence of intensified discriminatory behavior by landlords in the rental housing market during the eviction moratoria instituted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data collected from an experiment that involved more than 25,000 inquiries of landlords in the 50 largest cities in the United States in the spring and summer of 2020, our analysis shows that the implementation of an eviction moratorium significantly disadvantaged African Americans in the housing search process. A housing search model explains this result, showing that discrimination is worsened when landlords cannot evict tenants for the duration of the eviction moratorium.

Alina Arefeva, Kay Jowers, Qihui Hu & Christopher Timmins

The paper is “Discrimination During Eviction Moratoria”, released as an NBER working paper this month.

The post No Solutions, Just Tradeoffs appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>The post The urban economics of sprawl appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>Let’s take as a given that sprawl is “bad” urbanism, mediocre at best. Realistically, it’s rarely going to be transit-oriented, highly walkable, or architecturally profound.

So the question is whether outward, greenfield growth is necessary to achieve affordability. And the answer from urban economics is yes. You can’t get far in making a city affordable without letting it grow outward.

Model 1: All hands on deck

Let’s start with a nonspatial model where people demand housing space and it’s provided by both existing and new housing. Existing housing doesn’t easily disappear, so the supply curve is kinked.

A citywide supply curve is the sum of a million little property-level supply curves. We can split it into two groups: infill and greenfield, which we add horizontally.

If demand rises to the new purple line, you can see that the equilibrium point where both infill & greenfield are active is at a lower price & higher quantity than the infill-only line. The only way to get some infill growth to replace some greenfield growth, in this model, is to raise the overall price level. And even then, the replacement is less than 1-for-1.

Of course, this is just a core YIMBY idea reversed! In most U.S. cities, greenfield growth has been allowed and infill growth sharply constrained, so that prices are higher, total growth is lower, and greenfield growth is higher than if infill were also allowed.

At the most basic level, greenfield growth is simply one of the ways to meet demand. With fewer pumps working, you’ll drain less of the flood.

Model 2: Paying for what you demolish

Now let’s look at a spatial model where people will pay more per square foot when they are closer to downtown. (If the jobs are evenly dispersed everywhere, the place with the best job access is…the center. So the math is the same for a job-seeker.)

Of course, builders won’t supply new housing unless the price comes in above their construction cost. In general, more intensive types of building cost more per square foot. And building on large greenfield sites costs less (both via scale efficiencies and ease of access/staging) than small-site, infill growth. Finally, infill growth usually has to replace an existing land use.

Taking a specific transect across the city, let’s suppose that the existing value of parcels* as built is shown by the brown line.

[*existing value here has to be expressed in dollars per hypothetical square foot of the parcel as redeveloped. This is weird, but not hard to calculate in a model.]

To generate growth, the cost of development has to fit between the black willingness-to-pay line and the brown existing-value line. And infill typologies are often more expensive, per square foot, than greenfield ones.

What will infill housing cost? First, it will cost more than housing at the fringe, but that’s OK – the people at the core are benefiting in terms of commute time and job access. Paying more to be close to downtown is like paying more for a bigger house – you can’t complain.

Second, infill housing won’t be able to push the price per square foot of new construction below the cost of construction plus the value of existing development. As infill development runs out of abandoned warehouses and parking lots, that wedge will rise.

A successful YIMBY strategy via infill would run into a shrinking gap between falling prices and a rising existing-value wedge. If it got that far, I’d actually be surprised and impressed – but the point of this second model is that the price floor is higher.

Model 3: The tyranny of circles

What neither of the first two models could really tell us is how much greenfield matters as a quantitative matter. The first model shows how all supply channels are additive, the second shows that infill has a higher price floor. The final boss is the circle.

Back in model 2, it looked like there was about as much room for new development at that sharp dip just to the left of downtown (an old warehouse district, say) as in the greenfield areas at the edges. But cities don’t exist on a line – they usually approximate a circle.

In this map of DC, there’s a circle about 2 miles from the center and another about 20 miles from the center. How much more land does the outer one contain?

You don’t need pi for the answer: the outer circle is 100 times bigger in area. And it’s not even at the fringe in most places.

In most debates about the merits of the infill and greenfield, there’s an implicit “acres to acres” comparison – a parcel here versus a parcel there. But that misses the forest: the power of greenfield development is the incredible amount of land that is available for relatively low-cost conversion.

Counterarguments

Don’t greenfield infrastructure costs make it more expensive? If we didn’t subsidize sprawl, wouldn’t it mostly stop?

There are certainly gains from re-using existing urban infrastructure. But the dominance of horizontal growth across civilizations using a huge range of transportation technologies, taxation schemes, regulatory approaches, and infrastructure norms belies the idea that horizontal growth is mostly a subsidy phenomenon.

Sprawling Jakarta

Sprawling Istanbul

Sprawling Port-au-Prince

Sprawling Rotterdam

Sprawling Mombasa

Sprawling Rio de Janeiro

Cities also come with significant infrastructure costs that intensify with built and human density. I’m skeptical that a full, accurate accounting of costs can be done at the micro level. And the macro-level indicators, like overall tax rates, certainly don’t suggest large savings from density.

Can’t we build greenfield development that’s fully urban and transit-oriented?

There’s a huge variation in the quality of greenfield growth, and we can all applaud developers who are doing interesting things and building suburbs that have the bones for continued growth. But in American cities, transit is almost utterly useless to people living at the edge. It’s the tyranny of circles again: How many transit lines would need to reach the 20-mile radius perimeter to put everyone within a mile of transit? And how long will those commutes take?

Can we allow housing at the urban fringe but ban new highways?

This is just a recipe for stroads. Places like Northern Virginia that failed to build a network of limited-access highways instead have 6-lane arterials with traffic lights that mean they always run at half capacity. For a major city with serious demand pressure, building new highways or parkways is a good and necessary part of greenfield growth.

This is just part of a bigger principle for greenfield growth: Your suburb is never the last one. Much U.S. sprawl is built badly in the specific way that every town, every subdivision pretends that it will always be the last thing before farms and forests.

Yes In My Greenfield

The YIMBY movement is and should remain focused on re-legalizing infill growth. Strong Towns offers good principles for fiscal responsibility in moderate-demand places. There’s room for another policy movement focused on greenfield growth – getting the financing and governance right, planning for future growth, learning from successes and failures, promoting quality design that’s cheap enough for low-end development, and so on. If and when that movement arises, YIMBYs should greet it as a friend and ally: both are important to a future where housing is affordable.

The post The urban economics of sprawl appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>The post And the Oscar for best paper goes to… appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>

Affordability

The basic case for zoning reform, across the political spectrum, is that the rent is too damn high. Michael Manville, Michael Lens, and Paavo Monkkonen give a combative and accessible review of the evidence in their Urban Studies paper (2020). The principal drawback is that it is rapidly becoming dated, as evidence and research come in from more recent reforms. The most important of those may be Auckland’s, which Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy has reported in a few papers, including this Economic Policy Center working paper (2023). Using a synthetic control method (which is not perfect, to be sure), Greenaway-McGrevy finds that upzoned areas had 21 to 33 percentage points less rent growth.

A new candidate for the best review of the evidence on zoning reform and affordability is Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine M. O’Regan’s late 2023 working paper, “Supply Skepticism Revisited.”

Racial integration

Many authors from different disciplines have shown that both the intent and effect of zoning as practiced in the U.S. were racist and classist. That is, zoning policies have separated people by race, homeownership status, and income more than would have occurred in an unregulated market. Allison Shertzer, Tate Twinam, and Randall Walsh’s review of the evidence in Regional Science and Urban Economics (2022) is concise and helpful.

However, fewer authors have attempted to show that removing specific zoning restrictions reduces existing patterns of segregation. One is Edward Goetz, in Urban Affairs Review (2021). He makes a qualitative argument. I’m unaware of a good causal, quantitative paper showing how broad upzoning impacts local integration (but I would happily commission it if anyone wants to write it!)

Environment & climate

Along some dimensions, it is quite straightforward to argue that zoning reform benefits the environment. In other contexts, there’s more tension between environmentalism and other goals of liberalization. Does allowing denser subdivisions on the edge of Texas cities increase or reduce carbon emissions relative to baseline? I don’t know.

The IPCC chapter on urbanism (2022) stands out as a consensus summary if not as a model of persuasive prose.

Utopia City 2080, by DamianKrzywonos (CC 3.0)

Prosperity

Zoning reform can deliver a large boost to economic growth and living standards. I hesitate to accept any particular number, but the best work is clearly in Gilles Duranton and Diego Puga’s Econometrica paper (2023). From their conclusion:

Rights

Zoning directly constrains the right to use real property. It’s hard to turn that obvious statement into meaningful research. Bob Ellickson has done so as effectively as anyone, including in a widely-cited exploration of alternative, lighter-handed approaches to solving the problems zoning is purported to solve (University of Chicago Law Review, 1973).

There’s also a strain of thought around “the right to the city” and self-expression through activities from art to business, which need to take place somewhere. These literatures include interesting gems, like Beckers and Kloosterman’s 2014 study of pre- and post-war Dutch neighborhoods, but none that can make for real inclusion here.

Corruption

Property developers are almost always among the top donors to city councilmembers’ campaigns. As with segregation, this is a place where the problem is clearer than the solution. No recent paper can best Jesse Dukeminier and Clyde Stapleton’s 1961 classic in the Kentucky Law Journal, “The Zoning Board of Adjustment: A Case Study in Misrule.” I would welcome (and commission!) a paper testing whether broad upzoning (perhaps via state preemption) reduced corruption.

What else?

Add your own nominees in the comments!

The post And the Oscar for best paper goes to… appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>The post Rent regulation in MoCo appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>Adam Pagnucco responded with a series of posts at Montgomery Perspective about the prospect of rent control. His series begins with a great rundown of the economics literature on rent control, and continues by examining the effects of rent control in DC and Takoma Park respectively, with reflections from his personal experience living in a rent-controlled apartment in DC. In his conclusion, he cites the anemic pace of new housing construction to argue for a real way forward: instead of rent control, give the county’s recent liberalizing reforms time to work.

I contributed a post to the series demonstrating the effects of rent control on condo conversions within Takoma Park, which has had strict “rent stabilization” since 1981. I was able to exploit a natural experiment by examining one of the city’s boundaries, Flower Avenue, to be able to claim the rare causal effect: rent control caused condo conversions of 15 percent of multifamily buildings.

In a follow-up post, Adam links to a Takoma Park city report from 2017 which noted that Takoma Park’s young adult population declined from 2000 to 2015, and that no new multifamily rental units have been constructed in the city since the 1970s – before rent control was adopted.

Mercatus research assistant Eli Kahn helped draft this post.

The post Rent regulation in MoCo appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>The post Xiaodi Li, Misunderstood appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>EDITED 3/3: I’ve edited the post to take into account pushback from the authors I’ve criticized. Edits are in boldface.

The touchstone of YIMBYism is the sensible idea that housing markets follow the normal patterns of supply and demand.

It’s true. But it’s a deuce to measure, because housing markets don’t have sharp boundaries – they bleed across distance, tenure, and unit type. Suppose 200 new one-bedroom apartments open up in Bushwick. Do those mostly steal business from similar buildings in their immediate neighborhood? Or do they compete with all types of housing throughout the tri-state area? Or something in between?

Further complicating the story, new investment in a neighborhood can have “amenity” effects (positive or negative). These don’t work like supply and demand, but in any specific case it’s hard to distinguish the amenity effect from the supply/demand effect.

Neighborhood effects

A few years ago, most economists and urbanists (myself included) believed

- At the metro-area level, a broad increase in supply will lower rents.

- At the neighborhood level, amenity effects dominate.

That is, we thought the [edited 3/20] West Palm Bushwick apartments had a mostly-regional supply effect but an entirely local amenity effect. The evidence for this included many gentrification anecdotes: new “luxury” apartment buildings were accompanied by rising rents.

Enter Xiaodi (and friends)

Around 2017, a few economists started testing these beliefs. Could there be local supply effects after all? And do new buildings accelerate or decelerate gentrification? To my surprise, Li and others found that yes, there do appear to be hyperlocal effects from supply and demand.

In Li’s case, identification is based on timing: tall New York buildings take several years to build, and the unpredictability of the end date allows us to treat the year when new condos become available as essentially random (whereas the application date is not random). Li finds that new housing lowers rent within a 500-foot radius, but doesn’t have a statistically detectable in the 500 to 1,000 foot “donut” beyond that.

What Li’s paper doesn’t ask or attempt to answer is a different, broader question, what is the citywide effect of new supply on rent?

Cards on the table, I remain skeptical that Li is interpreting her core finding correctly (she can’t fully rule out disamenities). But Holleran and Schragger aren’t expressing skepticism – they’re misinterpreting her answer to one question as the answer to a very different question.

Clearing up a little misunderstanding

I expect that randos on Twitter (don’t harass them) are going to misapply Li’s work, assuming that the hyperlocal effect – a 10 percent increase in housing supply within 500′ decrease rent by 1 percent – represents the entire supply effect. But when housing scholars are taking it out of context, we need a reminder.

Law professor Richard Schragger cites Li’s paper in footnote 177 here, using it as evidence that new housing supply has “very limited” effects on “overall rents” in “specific locations”:

Some studies indicate a decrease in overall rents from increased market-rate housing, [176] but there are others that indicate the opposite or very limited effects overall. [177]

Schragger, The Perils of Land Use Deregulation, U. Pa. L. Rev. (p. 164)

Sociologist Max Holleran misunderstands it in a slightly different way:

One New York City study showed that every 10 percent increase in market-rate housing in a given neighborhood would result in a 1-percent reduction in rental prices: a supply effect but notone that gives much optimism to public policy officials tasked with solving the affordability crisis.

Holleran, Yes to the City (p. 13)

Both authors appear to clearly think that Li’s estimate is evidence about the overall effectiveness of housing supply in lowering rent. But that’s simply not the question she’s asking; her paper offers no evidence one way or the other on what the market-wide rent effect of a market-wide 10% increase in housing supply would be. Both authors identify Li’s study as a localized one, but then interpret her findings pessimistically. That’s the reverse: this study (along with those of Mast, Pennington, and others) made economists more optimistic about supply effects.

Li’s study doesn’t tell us what would happen if new buildings were simultaneously completed every 1,000 ft through New York City. It instead asks what happens when one – literally one – building is completed.

When Schragger returns to the question Li is actually answering

a few paragraphs later (“Places with a relatively low cost of living may lose that attribute once enough wealthier people move in”), he doesn’t cite her work.

The paper you’re looking for

What papers should they have cited? My go-to estimate is

Albouy, Ehrlich, and Liu‘s: a 3 percent increase in housing stock lowers rent by 2 percent. Older estimates were often in the 1:1 range, which is more optimistic about supply. I dug into this in a recent blog post here, highlighting that broad affordability and unit-specific affordability usually come from totally different channels:

I confronted the hard truth that supply changes need to be very large to make a real dent in prices. If, as Albouy, Ehrlich, and Liu estimate, it takes a 3 percent increase in the housing stock to bring prices down 2 percent, then a major metropolitan area needs a massive increase in housing to make a real dent in rent.

Can we get there faster with composition effects? Let’s do a quick back of the envelope. First, assume population and housing stock would grow 10% each at baseline, with no resulting change in price.

–> Supply only approach: we add 40% to the housing stock without changing the mix of housing types. Result: 20% affordability gains.–> Composition-only approach: we add 10% to the housing stock, but with the average price just 50% as high as the norm. Result: 5% affordability gains from lowering average price.

–> Mixed approach: we add 25% to the housing stock, with the average prices 75% as high as the norm. Result: 15% affordability gain (10% from supply, 5% from lowering average price).

Salim Furth, Is affordability just, “You get what you pay for”? Market Urbanism

How realistic are any of these scenarios? I’m not sure. But my takeaway is that supply remains the primary avenue for broad-based affordability gains. But the “you get what you pay for” and “only pay for what you want” channels are far more important for the affordability of a particular new housing unit.

There are questions worth asking about the impact of broad-based housing supply, and unresolved questions in the hyperlocal housing supply literature, but they’re different questions with presumably different answers.

marfis75 on flickr (CC-BY-SA)

The post Xiaodi Li, Misunderstood appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>The post The Homeownership Society Can Be Fixed appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>I think we can.

Demsas’s article is “The Homeownership Society Was a Mistake” in The Atlantic. In it, she diagnoses a major economic problem in America: our government often treats housing as an investment whose price should go up, while America needs housing to be a consumption good that is cheap to use. Her recommendation is that government should focus on making housing cheap and plentiful, “diminishing greatly” “its attractiveness as an investment.” And, if that wasn’t clear enough, she ends with “Let housing be a home; … Just don’t let it be an investment.”

Demsas’s problem is real, but her solution shocked me. It is both dangerous and unworkable.

Not treating housing as an investment is dangerous because housing is an investment. An investment moves value across time. If I spend money to build a house, that house is still valuable in 10 years. If I buy land, the land is valuable forever (barring disaster-movie disasters). In fact, housing is one of our country’s most valuable assets: land and buildings in America are worth more than the entire stock market. To not treat housing as an investment risks squandering that value.

Demsas’s solution is unworkable because we live in a democracy and the majority of voters own houses. Nationwide, 65% of housing units are “owner occupied” and homeowners are more likely to vote than renters. One study put it at 3% to 8% more likely. It is unreasonable for any elected official to go against homeowners.

Demsas’s solution can be ignored, but her problem should not be. Our government is currently prioritizing housing as an investment, rather than a consumption good, and that’s harming our country.

To understand the mechanism causing the harm, we need to look at housing as a risky investment. Land usually goes up in value, but it can go down. A dramatic example of that is Detroit from 2006 to 2009. Land prices plummeted. The price of the average single-family house on a lot fell by 55%. Some fell more.

The risk to homeowners is actually greater than that. A fall in land prices is usually caused by a worsening local economy. Over that same period in Detroit, unemployment rose to 16%. So, just when homeowners are most likely to lose their job, their asset falls in value.

Homeowners want to limit their risk. They elect officials who will protect their risky asset.

And, since homeowners are the majority, those elected officials go further by propping up that asset with tax benefits and competition-reducing zoning laws. The costs of those sweeteners are paid for by non-homeowners: we penalize renters. The penalties/favors drive low-wealth families to buy a home and go “all in” on a single risky asset. It is a matter of luck which ones profit from the bet.

By this mechanism, the Homeownership Society harms society. It penalizes the poor, encourages foolish risk, and generates inequality.

But the Homeownership Society is not all harms, or we would have gotten rid of it years ago.

Homeownership means permanence, which inspires residents to invest in their community. Homeownership means less risk, because any time you rent something there’s a risk that the renter damages it. Lastly, homeownership improves efficiency. Homeowners maintain their buildings better than renters. Homeowners are willing to invest in insulation, because they also pay the electrical bills.

Although Demsas doesn’t mention these benefits in the article, I’m sure she knows them. And I don’t think Demsas is against homeownership, per se. She is focused on the decisions of government officials to protect and prop up the price of housing. She sees their choice as lying on a single axis. They can choose high-priced housing or low-priced housing. You can see that in her self-question and self-answer: “How do we ensure that housing is both appreciating in value for homeowners but cheap enough for all would-be homeowners to buy in?” And seeing no options, she answers “We can’t.”.

I think we can. I think we can protect investments and lower the cost of housing. And, even more importantly, I think we can do it without denying the political reality that homeowners vote and that democratically elected officials serve (service?) the voters.

How do we get these benefits of homeownership without Demsas’s problems? Housing is two things: the land and the building on it. Most of Demsas’s negatives have to do with the land: it lasts forever (barring disasters) and swings up and down in value with the local economy. On the other hand, most of homeownership’s positives have to do with the building: lower risks, better maintenance, and better efficiency. If we can financially divorce the land from the building, we can get by Demsas’s impasse.

To do that, we need Financial Engineering. Financial Engineering is the art of writing a contract to allocate risks and financial incentives such that all parties benefit. An example contract that you’re familiar with is your insurance policy. You have risks you do not like: your house might burn down or your car might be hit by a garbage truck. The insurance company is willing to take on that risk if you pay a premium and a deductible. A financial engineer designed the contract with an “insured side” for you and an “insurer side” for the insurance company, to the benefit of both parties.

To solve Demsas’s problem and get past the impasse, we need a contract that pulls out all the “investment” qualities of the land and passes them on to an investor and leaves the “consumption good” qualities of the building with the homeowner.

I call this contract a “land-value contract”. With it, the homeowner will (effectively) sell the land under their house to the investor. If a property is valued at $300,000 for the house and $200,000 for the land, the homeowner signs the “seller side” of a land-value contract and receives $200,000. The investor signs the “buyer side” and delivers the $200,000. If the homeowner ever sells the property, the contract will end and the homeowner will pay the investor the current price of the land, which may be more or less than $200,000.

The investor is giving up $200,000 for this contract and taking on risk, so they must receive something in return. Thus, the homeowner pays a premium to the investor. The premium depends on the value of the land and is, effectively, the “ground rent”, the rental cost of the land under the house. The homeowner has, effectively, sold the land to the investor and now rents it back.

For housing policy geeks, this is almost Georgism. Homeowners pay rent for their land and those payments go to the nation’s investors (rather than the government). The contract can also be seen as a market-driven land trust. Homeowners own their home and pay rent for the land under their house, but those payments are done at market rates (not subsidized)

Homeowners would need a smaller down payment, since they are borrowing less and the risk is less. Homeowners would need to make a payment, the ground rent, that would change from year to year, but they already experience that with property taxes.

Investors should be interested in these contracts. A study of housing in multiple counties from 1950 to 2015 showed that the capital gain from housing has a risk-adjusted-return close to that of stock indices. And housing is weakly correlated with the stock index. The very wealthy, who own most stocks, could diversify by buying land-value contracts and the less wealthy, who currently put too much into a single piece of real estate, could diversify into stocks.

How does the land-value contract solve the problems of the Homeownership Society? It may pass the land value on to investors, but the land-value contract is still a large risky asset and won’t investors vote to protect against its risk? True, but the investors are different from the low-wealth homeowners going “all in” on a single risky investment. Investors diversify, by holding equities and by holding land-value contracts from many cities. And when someone invests in multiple assets, they care less about the ups and downs of any particular asset.

Land-value contracts will allow current homeowners to sell the land under their house and invest that money in stocks and in the land under every house in America. They would have to pay the ground rent for their house, but they would also receive the dividends and ground rents from other properties. Changes in the local ground rent are a risk, but it is a dramatically smaller risk than what homeowners hold right now. This lower risk weakens the motivations of elected officials to prop up those assets, at the cost of others.

Land-value contracts will allow current homeowners to sell the land under their house and invest that money in stocks and in the land under every house in America. They would have to pay the ground rent for their house, but they would also receive the dividends and ground rents from other properties. Changes in the local ground rent are a risk, but it is a dramatically smaller risk than what homeowners hold right now. This lower risk weakens the motivations of elected officials to prop up those assets, at the cost of others.

Land-value contracts could be created today by a company. A bank could sell them, combined with lower-downpayment mortgages. But it would be hard to launch this financial product. First, the bank would have to recruit new investors and educate them about the investment. Second, the bank would have to roll out the program nationwide, rather than in one city, to enable diversification. Lastly, and most importantly, there is no independent organization calculating the ground rent and land values in the contract. Customers would be scared to sign a contract where the bank determined that rate. Customers accept variable-rate mortgages, but that rate is set by an outside(ish) entity.

It would be easier for the government to launch the market. The government is independent(ish) and can compute the ground rent and land values. The government can also mandate the data (housing prices and rents) required to calculate those values. The federal government has an incentive to create this market: it implicitly backs mortgage-backed bonds and could reduce its risk by mandating the signing of land-value contracts by mortgage holders.

(Finance experts will point out that financial contracts on real estate already exist. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) has futures and options on the Case-Shiller Housing Index of 10 cities. These are based on the price of the land and the house on it. That, and other factors, make it difficult for homeowners to know how to offset their land’s value using these futures. These existing contracts are not the same as land-value contracts; ease-of-use and exact offsetting of risk matters.)

If you have access to The Atlantic, I encourage you to read Demsas’s article with the concept of land-value contracts in mind. The article is dense with arguments and supporting data. I believe the ability to separate the land’s value from the building’s value illuminates the arguments. Land-value contracts add a new axis, allowing us to see that cities prosper when (un-propped-up) land values increase and building costs decrease.

I value Demsas’s article for bringing attention to a problem. She wants housing to be a consumption good, like a TV or car. With land-value contracts, I think a house becomes exactly that. And it is achieved without denying the economic realities of housing and the political realities of our democracy. With land-value contracts, we can fix the Homeownership Society.

The post The Homeownership Society Can Be Fixed appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>The post Should governments nudge land assembly? appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>Graduated Density Zoning

Although he’s mostly known for parking research and policy, Donald Shoup responded to the ugliness of eminent domain in Kelo v. City of New London, with a 2008 paper suggesting “graduated density zoning” as a milder alternative. Graduated density zoning would allow greater densities or higher height limits for larger parcels – so that holdouts would face greater risk.

Samurai to Skyscrapers

Junichi Yamasaki, Kentaro Nakajima, and Kensuke Teshima’s paper, From Samurai to Skyscrapers: How Transaction Costs Shape Tokyo, is a fascinating and technical account of how sweeping changes put the relative prices of different-sized lots on a roller-coaster from the 19th century to the present. First, large estates were mandated as a way for the shogun to keep nobles under his close control. Then, with the Meiji Restoration, the nobles were released to sell their land, swamping the market and depressing prices. The value of land in former estate areas stayed low into the 1950s.

But with the advent of skyscrapers – which need large base areas – the old estate areas first matched and then exceeded neighboring small-lot areas in central Tokyo.

A meta-lesson from this reversal is that “efficiency” is a time-bound concept. One can imagine a 1931 urban planner imposing a tight street grid and forcing lot subdivision to unlock value on the depressed side of the tracks. That didn’t happen; instead, the large lots were a land bank that allowed a skyscraper boom right near the heart of a very old city, helping propel the Japanese economy beyond middle-income status.

We should take a long, uncertain view of all “efficiencies”. Instead of just optimizing under current conditions, imagine a range of conditions. Does a proposed policy improve life under most of those? Or are we better off with some apparent inefficiencies and redundancies that might have extremely high value in some states of the world?

Back to graduated density

With Tokyo as an inspiration for cautious policymaking, let’s turn back to Shoup’s idea. In Shoup’s telling, the reason that the government would value pushing the landowner to sell is that there are technical reasons (such as skyscraper footprint requirements) why small lots cannot achieve such high efficiency. Larger lots, bigger pie.

But if that’s the case – if small lots could not physically take advantage of the higher density or height limit available to large lots – then graduated density doesn’t change the game, as in Scenario 1 below.

Land assembly cases involve bargaining: if assembly can create $2 million, who gets that value? If either the owner or developer demand all of it, the other will walk away.

A case that Shoup doesn’t explicitly discuss is Scenario 2, where the small lot owner could gain some value from the more-intensive zoning, but is blocked by the graduated density provision.

The owner and the developer are still playing the same bargaining game in Scenario 2, but regulations have contrived to make the “pie” they’re splitting larger than it would be under equal zoning and to worsen the owner’s bargaining position.

There’s only a plausible role for government here if you believe that the bigger pie & worse bargaining position will make deals more likely. But even then, you have to overcome a serious moral question of whether the government should put its finger on the scales in a bargaining game. And you ought to be quite certain that a lot more assembly deals will take place, because the new regulations seriously decrease the potential unassembled value creation.

No (that’s my answer to the post’s title)

The value of treating everyone equally under law is sufficient for me to be opposed to graduated density zoning. But even for unobjectionable policies, the changing nature of “efficiency” along even such a simple dimension should be cause for greater humility.

Photo: Salim Furth

The post Should governments nudge land assembly? appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>The post Is affordability just, “You get what you pay for”? appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>This advice makes an economist’s mind race. We know, after all, that supply and demand work. But we’re not so sure about composition changes. If “affordability” is achieved by building units that people don’t want (in bad locations, too small, lacking valued attributes), then the price-per-unit can be low without actually benefiting people on their own terms. Even if existing homes are bigger than many people want, at least some of the price decline from building smaller homes is the “you get what you pay for” effect.

(Incidentally, this is the opposite concern from that held by econ-skeptics concerned about gentrification: they worry that new housing will be too good or that investment will upscale neighborhoods. This inverts the trope that economists “only care about money”.)

A few days later, a Maryland state senator asked me that very supply-and-demand question: “What’s the evidence that large-scale upzoning leads to affordability?” This is a tough question. First, large-scale upzonings are very scarce. Second, even if one occurs, it’s not in an experimental vacuum.

Three kinds of affordability

Let’s specify that an upzoning likely promotes affordability in three ways:

- Supply and demand

- You get what you pay for

- Only pay for what you want

The first channel is obvious – it explains why Cleveland is cheaper than Boston. The second source of affordability is valuable for people at risk of homelessness, but doesn’t make most people better off. The third source – what WNN recommends advocates emphasize – is that many regulations require people to pay for more housing (or pricey attributes) that they don’t want.

In a lot of cases, the last two effects will go together. Suppose a regulation forces me to pay for covered parking. I value the garage at $10,000, but it actually adds $30,000 to my home’s cost. Repealing it would save me $10k via “you get what you pay for” and $20k via “only pay for what you want.”

In my own research on Houston and Dallas minimum lot sizes this is exactly what I find: people value additional yard space, but not by as much as they’re paying for it.

Facing these questions, I was pleased to find that University of Michigan Ph.D. candidate Mike Mei had posted his job market paper – one of the few rigorous analyses that gets right to the heart of WNN’s advice and the senator’s question.

Finding an experiment in Houston

Houston’s choice to reduce minimum lot sizes to 1,400 square feet in 1999 was not random, and there’s no “control Houston” in an alternate universe. So Mei uses a “synthetic control” method to argue that reducing minimum lot size also reduced the size of newly built homes.

Synthetic controls use a weighted average of a “donor pool” of similarly situated cities that tracked the “treated” city (i.e. Houston) before a policy change. Mei’s synthetic control is reasonably convincing, although it relies mostly on just three donors.

This is a very useful and direct result for those of us advocating for minimum lot size reductions: even though developers squeeze as much house as they can onto Houston’s small lots, those houses are still smaller than the alternative.

Affordability without supply effects

Mei could have tried the same synthetic method to measure the impact of Houston’s reform on new home prices. But that wouldn’t let us distinguish between the various sources of affordability.

Instead, Mei uses a model of household decisions, taking into account household income and size (i.e., number of people). Intuitively, bigger households need bigger houses. His model allows migration, has no limits on how many houses are built, and assumes away location preferences, which effectively shuts down supply-and-demand as a source of affordability. That lets him isolate the gains from the “only pay for what you want” channel.

(There’s another minor “reallocation” channel in his model, but it wouldn’t show up in an affordability calculation, so let’s set it aside.)

Figure 14(a) shows that, in the long run, the value of only paying for as much house as they want will benefit Houston households by between zero and $28,000, with generally higher values for lower-income households. The average benefit is $18,000, which is one-third of the median income at the time of the reform. Figure 14(b) shows that households of all sizes benefit, but the benefits are greatest for smaller households.

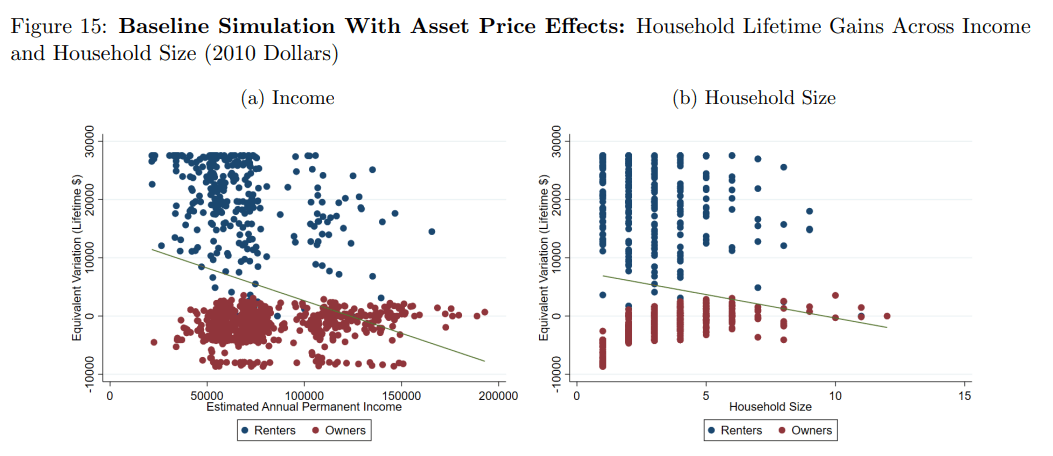

For Figure 15, Mei adds very simplified asset holdings, allowing households to rent housing and then become owners. If this simplification holds up, it shows that virtually all the benefits flow to people who were renters before the policy was introduced. Homeowners lose a little bit on average. The biggest losses are for owners who had small houses before the reform; those face the biggest increase in competition.

(It’s not clear to me why there’s a rigid ceiling at about $28,000 in gains – that’s probably an artifact of the model.)

Does supply even matter?

In my conversation with the Maryland senator, I confronted the hard truth that supply changes need to be very large to make a real dent in prices. If, as Albouy, Ehrlich, and Liu estimate, it takes a 3 percent increase in the housing stock to bring prices down 2 percent, then a major metropolitan area needs a massive increase in housing to make a real dent in rent.

Can we get there faster with composition effects? Let’s do a quick back of the envelope. First, assume population and housing stock would grow 10% each at baseline, with no resulting change in price.

- Supply only approach: we add 40% to the housing stock without changing the mix of housing types. Result: 20% affordability gains.

- Composition-only approach: we add 10% to the housing stock, but with the average price just 50% as high as the norm. Result: 5% affordability gains from lowering average price.

- Mixed approach: we add 25% to the housing stock, with the average prices 75% as high as the norm. Result: 15% affordability gain (10% from supply, 5% from lowering average price).

How realistic are any of these scenarios? I’m not sure. But my takeaway is that supply remains the primary avenue for broad-based affordability gains. But the “you get what you pay for” and “only pay for what you want” channels are far more important for the affordability of a particular new housing unit.

The post Is affordability just, “You get what you pay for”? appeared first on Market Urbanism.

]]>