Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Davis, CA, is a small college town a twenty minutes’ drive outside of Sacramento (on a good day). It has a vacancy rate on par with Manhattan despite being surrounded by flat, developable farmland. Some critics attribute this absurd vacancy rate to Measure R, a ballot initiative approved by Davis residents in 2000 that requires a public vote on any peripheral development. Since it’s passage, three developments went up for a vote, and all of them failed. The group that defends Measure R is known as the “Citizens for Responsible Planning” or CRP. Throughout various development battles, CRP has strategically utilized air quality concerns to push new development further away from existing neighborhoods. They opposed the most recent Measure R development, Nishi Gateway, because toxic air quality made the site virtually uninhabitable, at least in their minds! In fairness: the site is sandwiched between railroad tracks and a major highway, Interstate 80. So it’s a real concern. But fast-forward just six months later, and CRP is demanding the University of California, Davis, the area’s largest employer, dramatically expand its on-campus housing options for students, staff, and faculty. In an effort to appear proactive, they produce a map of optimal sites to locate student housing on the UC Davis Campus. One of the sites they select is adjacent to the Nishi parcel they so aggressively opposed development on just six months earlier. Another parcel they suggest building housing on is also sandwiched between the same railroad tracks and highway that Nishi sat between, but just a couple miles further south (and further from existing neighborhoods). You can see all of this in a map provided below, where the Nishi site they killed at the ballot is marked in red and the sites they claim to support student housing on are colored in blue: […]

President Trump has threatened to withhold all federal funds from so-called sanctuary cities–municipal governments that do not enlist their police departments in the president’s mass deportation plan. If he makes good on his threat, cities that insist on maintaining their sanctuary status can offset revenue losses with two policies: liberalizing land-use regulation and depoliticizing public land sales. It’s unclear exactly how much money each city would lose by maintaining its sanctuary status, but New York City, to name one example, relies on federal funding for 10% of its budget, according to state comptroller estimates. A sudden drop of that magnitude would devastate many jurisdictions, and Miami-Dade County has already caved. However, a handful of cities with high rents and very restrictive land-use regulations could dramatically increase property tax revenue and the value of city-owned real estate through liberalization. Millions of Americans would love to live in cities like New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, San Jose, Austin, Portland, and Denver, but legal restrictions on what can be built limit the number of housing units available and increase the cost of each unit. Some estimates have found that regulation alone accounts for fifty percent of the cost of housing in San Francisco. At the same time, land-use regulation has the opposite effect on the price of land itself. A plot of land with limited legal potential for development is worth much less than a plot a developer could use to build a large, lucrative building. Economist Keith Ihlanfeldt has found that the decrease in land values more than offsets the increase in home prices—meaning some cities are decreasing potential revenues by restricting development. San Francisco has large neighborhoods of single-family homes where rent levels would sustain large apartment towers. The drastic mismatch between what is currently allowed and what consumers demand suggests that land values would skyrocket if restrictions were relaxed. […]

[This piece was originally published on the site Better Institutions.] On March 7th, Los Angeles is going to vote on the type of city it wants to be. The vote will be over Measure S, formerly known as the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative (NII), which seeks to limit housing development in the city. Backers of the initiative claim that City Council is too beholden to developers, and that the pace of new housing and commercial development in the city is out of control. They also express concern that “mega projects” are making Los Angeles less affordable, since few new homes are being targeted at low and moderate income households. It’s a really bad plan, but calling Measure S “bad” doesn’t go nearly far enough. It is, in fact, the Donald Trump of ballot initiatives. It’s a cynical effort to co-opt a legitimate sense of frustration—frustration felt by those who haven’t shared in the gains of an increasingly bifurcated society—and to use that rage and desperation for purely selfish purposes. It invites us to vent our frustrations and, in so doing, to further enrich those who helped to engineer our ill fortune. And as with Trump, a Measure S victory will roll back the clock on years of steady progress. Since I think there are a lot of folks out there who genuinely haven’t made up their minds about the initiative, or aren’t yet familiar with it, I’d like to summarize some of the most important reasons to oppose it when it comes time to vote this March. 1. IT WILL MEAN FEWER AFFORDABLE HOUSING UNITS FOR LOW INCOME HOUSEHOLDS. The Coalition to Preserve LA, which is backing the initiative, is turning this into a referendum on housing development in Los Angeles. They’re arguing that new homes have “wiped out thousands of […]

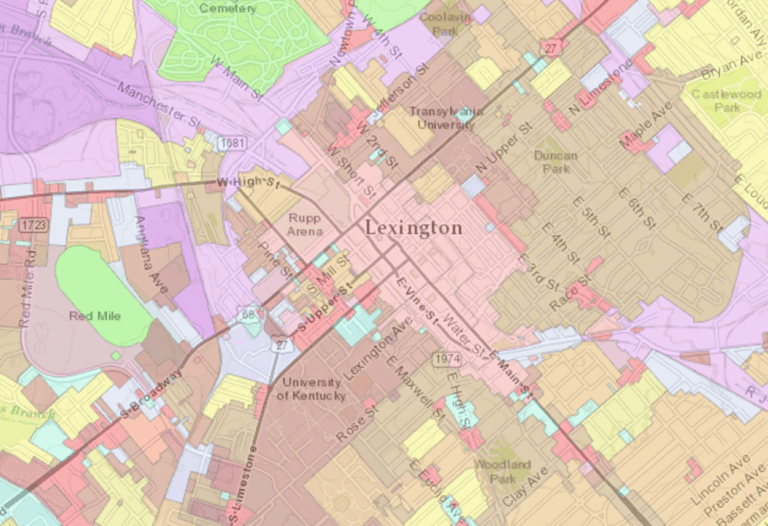

Lexington, Kentucky is a wonderful place, and that’s getting to be a problem. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the city: its urban amenities, thriving information economy, and unique local culture have brought in throngs of economic migrants from locales as exotic as Appalachia, Mexico, and the Rust Belt. The problem, rather, is that the city isn’t zoned to support this newfound attention. Over the past five years, the city has grown by an estimated 18,000 residents, putting Lexington’s population at approximately 314,488. Lexington has nearly tripled in size since 1970 and the trend shows no signs of stopping, with an estimated 100,000 new residents arriving by 2030. Despite this growth, new development has largely lagged behind: despite the boom in new residents, the city has only permitted the construction of 6,021 new housing units over the past five years—not an awful ratio when compared to a San Francisco, but still putting us firmly on the path toward shortages. The lion’s share of this new development has taken the form of new single-family houses on the periphery of town. Create your own infographics. Sources: ACS/Census Bureau At the risk of sounding like a broken record, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with single-family housing on the periphery of town. Yet in the case of Lexington, it’s suspect as a sustainable source of affordable housing. Lexington was the first American city to adopt an urban growth boundary (UGB), a now popular land-use regulation that limits outward urban expansion. As originally conceived, the UGB program isn’t such a bad idea: the city would simultaneously preserve nearby farmland and natural areas (especially important for Lexington, given our idyllic surrounding countryside) while easing restrictions on infill development. Create your own infographics. Source: Census Bureau The trouble with Lexington is that the city has undertaken […]

Planners, like all professions, have their own useful mythologies. A popular one goes something like this: “Many years ago, us planners did naughty things. We pushed around the poor, demolished minority neighborhoods, and forced gentrification. But that’s all over today. Now we protect the disadvantaged against the vagaries of the unrestrained market.” The seasoned—which is to say, cynical—planner may knowingly roll her eyes at this story, but for the true believer, this story holds spiritual significance. By doing right today, the reasoning goes, planners are undoing the horrors of yesterday. This raises the question: are planners doing right today? That’s not at all clear. Just ask Hinga Mbogo. After emigrating from Kenya, Mr. Mbogo opened Hinga’s Automotive in East Dallas in 1986. Mr. Mbogo’s modest business is precisely the kind of thing cities need, providing a service for the community, taxes for the city, and blue-collar jobs. While perhaps not of the “creative class,” Mr. Mbogo and his small business represent the type of creative little plan that cities cultivate and depend on. Hinga’s Automotive has thrived for 19 years and looked primed for another 19. Unfortunately for Mr. Mbogo, Dallas planners had other plans. In 2005, the city rezoned the area to prohibit auto-related businesses. While rezonings—particularly upzonings—aren’t necessarily a bad thing, Dallas planners opted to force their vision through and implemented a controversial planning technique known as “amortization.” Normally when planners rezone an area, they allow existing uses that run afoul of the new code to continue operating indefinitely. These are known as “non-conforming uses” and they’re common in neighborhoods across the country, often taking the form of neighborhood groceries, restaurants, and small industrial shops. Yet under amortization, the government forces non-conforming uses to cease operating without any compensation. In the case of Hinga’s Automotive, this means […]

The Atlantic Magazine’s Citylab web page ran an interview with Joel Kotkin today. Kotkin seems to think we need more of something called “localism”, stating: “Growth of state control has become pretty extreme in California, and I think we’re going to see more of that in the country in general, where you have housing decisions that should be made at local level being made by the state and the federal level too. You have general erosion of local control.” In fact, land use decisions are generally made by local governments–which is why it is so hard to get new housing built. This is as true in California as it is anyplace else; when Gov. Brown tried to make it easier for developers to bypass local zoning so they can build new housing, the state legislature squashed him. Local zoning has become more restrictive over time, not less. And the fact that state government has added additional layers of regulation doesn’t change that reality. But did the Atlantic note this divergence from factual reality, or even ask him a follow-up question? No, sir. Shame on them!

I just read a law review article complaining that some white areas in integrated southern counties were trying to secede from integrated school systems (thus ensuring that the countywide systems become almost all-black while the seceding areas get to have white schools), and it occurred to me that there are some similarities between American school systems and American land use regulation. In both situations, localism creates gaps between what is rational for an individual suburb or neighborhood and what is rational for a region as a whole. In particular, it is rational for each suburb to have high home prices (because that means a bigger tax base)- but I don’t think San Francisco-size rents and home prices are rational for a region as a whole. Similarly, it is rational for each individual neighborhood within a city to have restrictive regulations, because if one neighborhood is less restrictive it suffers from whatever burdens might result from new housing, without the broader benefit of lower citywide housing costs. How are school districts similar? Since the prestige of a neighborhood is related to its school district, and the prestige of school districts depends on their socio-economic makeup, it is rational for each suburb (or city neighborhood) to be part of a school district dominated by white children from affluent families, rather than to be part of a socially and racially diverse district. But if every middle-class or affluent area draws school district lines in a way that excludes lower-income children, the poor people are all concentrated in a few poor school districts (such as urban school districts in Detroit and Cleveland). Is this rational for the region as a whole? I suspect not.

The Cato Institute’s Vanessa Brown Calder is skeptical of the Obama administration’s suggestion that state governments can play a role in liberalizing land-use regulation, a policy area usually dominated by local governments. In an otherwise thoughtful post responding to a variety of proposals, she writes that federal and state-level bureaucrats should step aside to allow local advocacy groups to fill the void. She asks, “Who better to determine local needs than property owners and concerned citizens themselves?” Pretty much anyone, really. Local control of land-use regulation is a mistake and concerned citizens in particular are ill-suited for making decisions about their neighbors’ property. Supporters of free societies usually oppose local control of basic rights for good reason. Exercising one’s rights can be inconvenient for or offensive to nearby third parties. Protesters slow traffic, writers blaspheme, rock bands use foul words, post-apartheid blacks live wherever they choose with no regard for long-held South African social conventions, and so on. These inconveniences obviously don’t override rights to freedom of expression, but lower levels of government might be persuaded by people whose sensibilities are offended by these expressions. People are more likely to favor restrictions on rights when presented with a specific situation than they are when asked about general principles. People are even more likely to favor restricting a specific, disliked person’s rights. The landmark First Amendment case, National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie, is instructive. The plaintiffs, American Nazis planning a parade through a neighborhood populated by Holocaust survivors in Illinois, sued on First Amendment grounds when the local government tried to prevent them from carrying swastikas. The Supreme Court eventually ruled in favor of the Nazis because the First Amendment protects peaceful demonstrations with no regard for the vile or hateful content of the ideas being promoted […]

I think the most useful way to think about NIMBYism is as a neighborhood-centered phenomenon. When people shop for homes, they shop for specific, physical features of a dwelling, of course, but mainly they shop for neighborhoods. The quality of neighborhood amenities — interpreted broadly to include things like school quality and access to the CBD — varies wildly from neighborhood to neighborhood, and thus does the amount people are willing to pay for those amenities. What NIMBYs are really after is limiting access to neighborhood amenities, mostly by limiting the quantity of housing. Neighborhoods (at least the ones empowered politically) do their best to hold housing below the market-clearing quantity. This ensures that the value of neighborhood amenities is capitalized into home prices. Without quantity controls, the “nicest” neighborhoods would be the densest. Instead, thanks to zoning, they’re simply the most expensive. There’s a steep premium for buying into the neighborhood club. Here’s evidence in favor of the “club” theory from L.A. planner C.J. Gabbe. (H/t Urbanize.LA.) Gabbe asks the question, “Where do upzonings and downzonings happen?” To answer it, he looked at how the zoning of each of L.A.’s 780,000 parcels changed between 2002 and 2014, and tallied whether a lot was “upzoned” or “downzoned”, as measured by the change in allowed residential density. The first striking result was how few of the parcels were either upzoned or downzoned: an average of just 225 acres were upzoned and 216 acres downzoned annually between 2002 and 2014. That is, less than two-tenths of one percent of L.A.’s land area was upzoned or downzoned each year. Given the surge in demand for housing in L.A., especially over the last 6 years or so, that’s remarkably little. But the other thing Gabbe documents is that resistance to zoning really does seem to […]

Central Austin needs more housing. Prices have been rising, more and more people want to live where they have short commutes, but are only able to afford homes near the periphery. We have a long-term plan to alter our land development code in a way that would help…but our need is now. What options are available today? END PARKING REQUIREMENTS IN WEST CAMPUS Every year, West Campus adds more and more dense student housing, and, along with it, pedestrian amenities like wide sidewalks and street trees. A parking benefit district meters on-street parking with proceeds plowed back into neighborhood improvements. Surveys have shown the vast majority of West Campus students get around without cars. Allowing housing for students without parking could allow denser housing, lower construction costs, or allow more creative buildings that take advantage of unique lots. Removing minimum parking rules has already resulted in a few buildings downtown targeting markets that either don’t need cars or have other places to park them; this could be even more true in student-rich West Campus. REDUCE PARKING REQUIREMENTS NEAR TRANSIT ROUTES The same logic of reducing parking requirements applies outside the student market to apartments near transit routes. More and more people in Austin want to live car-free or car-light. That is easiest to do in buildings created with that lifestyle in mind–a step that can both reduce construction costs and allow room for improving other amenities. Long-term, if Austin wants to be a sustainable city, parking-free typologies should be allowed everywhere. However, in much of Austin, we wrongly treat scarce on-street parking as an endless “commons” rather than managing it as a scarce resource. This means that it may be wiser to improve incrementally–reducing off-street parking requirements, improving on-street parking management, and improving transportation options. IMPLEMENT THE DOWNTOWN AUSTIN PLAN New high-rise towers are being constructed in downtown Austin all the time–but downtown is more than just the Central Business District. […]