Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Over the past few years, Japanese zoning has become popular among YIMBYs thanks to a classic blog post by Urban kchoze. It’s easy to see why: Japanese zoning is relatively liberal, with few bulk and density controls, limited use segregation, and no regulatory distinction between apartments and single-family homes. Most development in Japan happens “as-of-right,” meaning that securing permits doesn’t require a lengthy review process. Taken as a whole, Japan’s zoning system makes it easy to build walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods, which is why cities like Tokyo are among the most affordable in the developed world. But praise for Japanese zoning skirts an important meta question: Why did U.S. zoning end up so much more restrictive than Japanese zoning? To frame the puzzle a different way, why did U.S. and Japanese land-use regulation—which both started off quite liberal—diverge so dramatically in terms of restrictiveness? I will suggest three factors; the first two set out the “why” for restrictive zoning and the third sets out the “how.” Any YIMBY efforts to liberalize cities in the long term must address these three factors. First, the U.S. privileges real estate as an investment where Japan does not, incentivizing voters to prohibit new supply with restrictive zoning. Second, most public services in the U.S. are administered at the local level, driving local residents to use exclusionary zoning to “preserve” public service quality. Third, the U.S. practice of near-total deference to local land-use planning and widespread use of discretionary permitting creates a system in which local special interests can capture zoning regulation and remake it around their interests. At the outset, why might Americans voters demand stricter zoning than their Japanese counterparts? One possibility is that they are trying to preserve the value of their only meaningful asset: their home. In the U.S., we use housing […]

While reading someone else’s work, I recently ran across an article by David Cay Johnston of the New York Times, claiming that overseas oligarchs turning apartments all over the world into unused “ghost apartments”. In this article, Johnston writes: “In Paris, for instance, one apartment in four sits empty most of the time.” This claim struck me as so astonishing that as to be implausible, for the simple reason that in other “global” cities vacancy rates are much lower. For example, in New York only 9 percent of housing units are vacant, and most of those units are currently for sale or rent.* Even this vacancy level should not be particularly astonishing, since cheaper American cities often have higher vacancy rates. For example, Houston has an 11 percent vacancy rate, and Atlanta has an 18 percent vacancy rate. After googling “one in four paris apartments vacant” I found an article claiming that 26 percent of apartments in four Paris arrondisements (neighborhoods) is vacant- a much narrower claim, comparable to an assertion that one in four midtown Manhattan apartments is vacant. One would think that a journalist as distinguished as Johnston would know the difference between “Paris” and “some parts of Paris.” A more recent article claims that only 7.5 percent of Paris apartments are vacant- a lower vacancy rate than that of New York. Moreover, we don’t know what the local media means by “vacant.” Does this category limited to apartments that are unused 365 days a year? What about units that are rented out now and then through Airbnb? Or units that are currently being advertised for rent or sale? I suspect that the true number of “ghost apartments” is far lower than 7.5 percent, since in London (another “global city”) less than 1 percent of housing units are […]

Alain Bertaud’s long awaited book, Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, is out today. Bertaud is a senior research scholar at the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management and former principle urban planner at the World Bank. Working through a pre-release copy over the past few weeks, I can confidently say that the book is an instant classic of the urban planning genre, and will be of significant special interest to market urbanists in particular. Rare among writers in this space, Bertaud brings an architect’s eye, an economist’s mind, and a planner’s experience to contemporary urban issues, producing a text that is theoretically enriching and practically useful. Alain and Marie-Agnes—his wife and research partner—have lived in worked in over a half-dozen cities all over the world, from Sana’a to Paris to San Salvador to Bangkok. For the reader, this means that Bertaud can speak from experience, supplementing data and theory with entertaining, real world examples and war stories. Order your copy today!

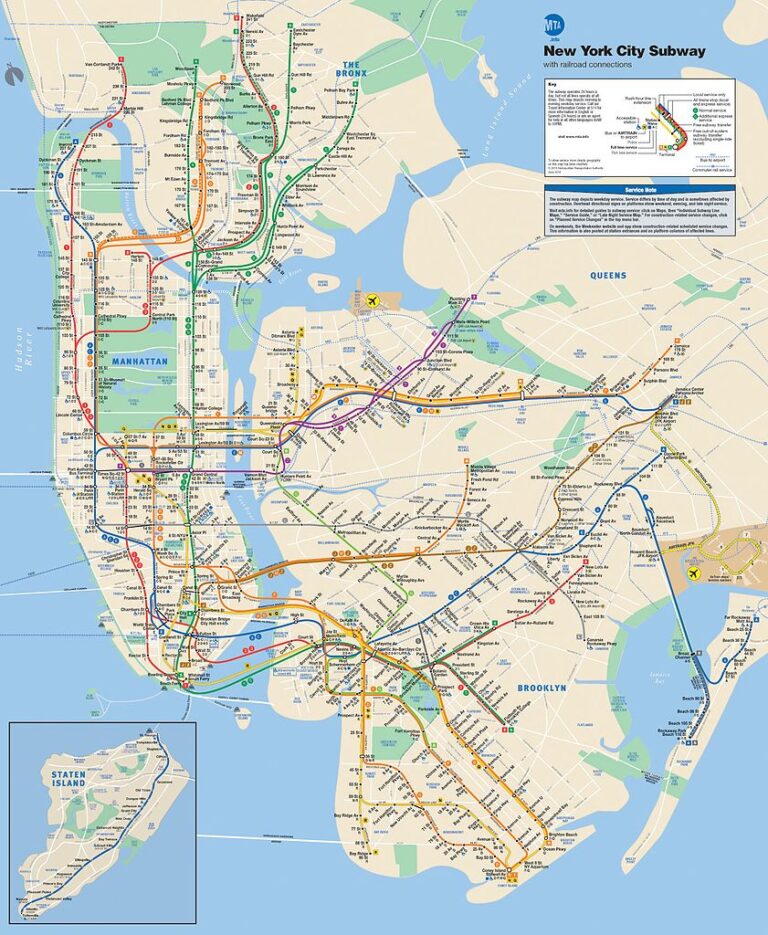

This year, for the first time since 1979, New York City has revamped its subway map. A quick glance shows a change in the background tinge from light tan to light green – most pleasant. To my relief, however, on closer inspection nothing essential has changed from the last version. Thank goodness it still doesn’t look anything like the map of London’s Underground. London’s map has been touted as the path-breaking paradigm of subway maps, the object of widespread acclaim and imitation. Indeed, most major cities’ transit systems have adopted the map’s efficient symmetry, which was created by Harry Beck back in 1931 during the heyday of high modernism. Here it is (pdf). It’s easy to see why it has won praise. It’s beautiful, looking like a two-dimensional version of a uranium molecule or the lattice of some fantastic crystal. The same could be said for the maps of the underground systems of Paris and Tokyo. It’s about Usefulness As you’ve probably already guessed, however, I don’t like it. And it’s not about aesthetics. Here’s the problem: I’m just one person, of course (although here’s another guy who seems to agree with me), but when I’m in London I find myself constantly frustrated when I try to get from place to place using that map. The problem is that I need two maps: the Underground map to tell me how to get from, say, Paddington to Notting Hill Gate, and a street map to tell me exactly where the heck Notting Hill Gate is in relation to Paddington. The former abstracts from so much street-level detail that, unless you’re already familiar with the layout of London, the map, rather increasing the efficiency of travel via mass transit, actually makes it more cumbersome. New York City’s subway map on the other […]

Four years ago my wife and I decided to take our son to a special and slightly unusual restaurant to celebrate his birthday. We were in Tokyo at the time and gave the taxi driver what we thought was the address for the restaurant – it had names and numbers on it. Cabbies in Tokyo, and in Japan in general, are renowned for their courtesy, the cleanliness of their cabs, and their driving skill. We were very surprised, therefore, when our driver suddenly pulled over and told us that “the restaurant is somewhere around here,” let us off, and drove away. After several minutes of search, we did manage to find the restaurant around the corner about a block or so away. We had a great meal, but the memory of that experience has always been something of a puzzle – until now. This summer we returned to Tokyo for a family vacation, and while relaxing in our hotel room I found myself thumbing through a guide book we had brought along, Japan Made Easy, in which I found this startling statement: “Tokyo … has thousands upon thousands of streets, but fewer than one hundred of them have names.” A quick check of Google Maps seems to confirm this assertion. (Hat tip to Jeremy Sapienza). More than One Way to Address a Letter This raises some obvious questions, such as how one addresses a letter. The guide says: …[T]he addressing system in Japan has nothing whatsoever to do with any street the house or building might be on or near. Addresses are based on areas rather than streets. In metropolitan areas the “address areas” start out with the city. Next comes the ku, or ward, then a smaller district called cho, and finally a still smaller section called banchi. This […]

There is always the lurking suspicion that great urbanism is a museum piece, something we cannot recreate. We have to console ourselves with guarding what’s left. Even then, some feel it unfit for ‘modern life,’ that humans cannot live as their recent ancestors had. Urbanists tend to celebrate cities and spaces of great renown, which makes remaking our own little corner of the world seem futile. I spent a year living in Europe–visiting Belgium, Italy, Spain and France, among other places–and found that the best places were not the big cities, but old villages, often very wealthy in times past. And it’s easy to miss what’s special about these quiet gems: the little streets and paths within them that people call home. A newly-built mall in Leuca, Italy showcases an older design sensibility A bike tour led me to several towns in southern Italy—among them, Castro was my favorite aesthetically, with warm, immaculate streets around the center that were nonetheless devoid of many people. Castro, Italy Castro, Italy Long before going to Europe, I had seen this meme photo: Lo and behold, one such camera appeared right above where I parked my bike. But overall, Bari’s old city was my favorite, with all the life coarsing through its streets. Families would open their doors and put out folding chairs in the streets. They made the streets their living room, while literally airing their dirty laundry in the rafters between buildings. Bari, Italy A quiet street in Leuven, Belgium—perhaps my favorite of all A Flemish parking lot—the Grand Beguinage, Leuven, Belgium Reims, France In Reims, I got to tour some underground cellars that formerly stored champagne. With cool temperatures, high ceilings and lush moss lining the walls, I thought—I’d love to live here! Should people be banned from […]

As an economics professor, I often witness the surprise of my students when I explain how something as important as the market for food or clothing is self-regulating. True, there are quality and safety regulations that attempt to control potential hazards “around the edges” of these vital markets, but by far the heavy lifting is done by competition among rival firms in the same industry. Trying to sell tainted food or shoddy clothing in a competitive market without special privileges will either put you out of business or make you very quick on your feet. And I get great satisfaction when I see students realize that advertising, free entry, and entrepreneurship, in the context of economic freedom, are what keep goods and services safe, cheap, and of good quality. Witness what happens when drugs and prostitution are prohibited: overly concentrated, dangerously mixed narcotics and significantly higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases, both accompanied by violence and corruption. Here government intervention thwarts self-regulation. The Nonmarket Foundations of the Market Process In the past dozen years or so, as a result of my research interest in the economy of cities, which was sparked by my discovery of the writings of Jane Jacobs, I’ve come to appreciate more and more the nonmarket foundations of the market process. Some of this has been reflected in previous Wabi-sabi columns that were concerned with social networks (most recently last week but also here). Without norms that say, for example, treating strangers fairly and trading with them is good, or that lying to and stealing from strangers is bad, human well-being couldn’t have soared to the heights of the past 200 years, especially the last 60. Now obviously none of this would have happened either without the widespread acceptance of private property, freedom of association, and the […]

I’ve been enjoying the series Meet the Romans, and episode 2 really revealed what I love about many ancient Roman cities. I’ve been to quite a few, though often without knowing beforehand that they were ancient Roman cities. These include cities like Dubrovnik, Split, La Spezia, Florence, Istanbul, Budapest, and yes, Rome. The attributes I’ve come to love include: 1. very narrow streets, often not accommodating cars 2. countless 4- to 6-story buildings with a variety of units, from cheap tiny units to large family units with courtyards 3. built into the 1st floor of these buildings are tiny shops – everything from restaurants to banks to bakeries 4. in ancient Rome most housing units weren’t used for much more than sleeping – living was done in the city. You often didn’t have a kitchen, laundry facilities, or even a bathroom. The host Mary Beard tells about the horrors of these things (barely enough room to lie down, the danger of dark small alleys), but I think in a modern world they’d be wonderful (ok, keep private bathrooms). Walk to your job, spend time in a vast variety of restaurants or pubs, experience the feeling of a busy narrow street, chat with neighbors at a public park, and take your kids to relax and play at the public bath or let them play in a public square while you grab a cappuccino. This is heaven to me. The only reason most modern cities aren’t like this is because we force them not to be. We require minimum space for all housing types, design our streets for cars instead of people, limit the height of buildings in most places, and separate our retail from our living zones. The effect is to push the less-rich outward, separate us from other people, and […]

People in the American Midwest are said to be on average more conservative and more libertarian than people who live on the East and West Coasts. And that in turn is because people in rural areas are said to be more strongly tied to the traditions of individualism and self-reliance than those in big cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago—who politically are more statist and tend to see government as a first-responder to perceived economic and social problems. We could go back and forth arguing with conflicting evidence on urbanity and ideology that depend on, for example, whether you use “Republican” and “Democrat” as proxies for “right-wing” and “left-wing,” whether you’re comparing states or counties, and so on. So for the sake of argument I will concede that in today’s United States “urban” means statist and “rural” means conservative and libertarian. Does it follow then that people who live in dense cities are necessarily more statist than people who live in lower-density rural areas, exurbs, and suburbs? I think not. I believe the positive correlation between political conservatism and libertarianism and rural or “agricultural” living is an historical anomaly; that historically the countryside has been a great obstacle to liberty while cities have been the places where liberty and the fruits of liberty have flourished. (I place “agricultural” in quotation marks because only about 2 percent of Americans actually live on farms.) American Conservatism and the Libertarian Movement There are at least two meanings attached to the word “conservative.” The more general meaning refers to someone who has an above-average attachment to certain ideas and ways of living that are considered traditional. Now, few people like change as such and everyone has an attachment to at least some ideas of the past, whether conservative or liberal, libertarian or […]

My guest this week is Anthony Ling. Anthony is founder and editor of Caos Planejado, a Brazilian website on cities and urban planning. He also founded Bora, a transportation technology startup and is currently an MBA candidate at Stanford University. He graduated Architecture and Urban Planning at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and worked with Isay Weinfeld early in his career. Read more about the ideas discussed in this week’s episode: Be sure to check out Caos Planejado. Whether Portuguese is your native language or you’re interested in Brazilian urban planning issues, it’s a fantastic resource. Learn more about the emergent order of informal favela development. Everyone interested in urban planning should, at the very lease, read the Wikipedia article on Brasilia. Learn more about on-demand transit. Help spread the word! If you are enjoying the podcast, please subscribe and rate us on your favorite podcasting platform. Find us on iTunes, PlayerFM, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Our theme music is “Origami” by Graham Bole, hosted on the Free Music Archive.