Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Someone just posted a video on Youtube using Houston, Texas as an argument in favor of zoning. The logic of the video is: Houston is horrible; Houston has no zoning; therefore every city should have conventional zoning. This video and its logic are impressively wrong, for several reasons. First, I’ve been to Houston and most of what I saw looks nothing like the video – there are plenty of blocks dominated by houses and the occasional condo. Second, most of the photos in the video could have easily happened in a zoned city, because one block in a neighborhood could be residential and the next block could be commercial, so the commercial or industrial activities can be easily viewable from the residential areas (not that anything is wrong with that). Third, most other automobile-dependent cities aren’t any prettier than Houston; a strip mall in Houston doesn’t look any worse than a strip mall in Atlanta. Fourth, it completely overlooks the negative side effects of zoning as it is practiced in most of the United States (many of which have been addressed more than once on this site). Typically, residential zones are so enormous that most of their residents cannot walk to a store or office. Moreover, density limits everywhere limit the supply of modest housing, thus creating housing shortages and homelessness. Finally, Houston’s negative characteristics are partially a result of government spending and regulation; as I have written elsewhere, that city has historically had a wide variety of anti-walkability policies, so it is far more regulated than the video suggests.

One common argument against new housing is that the laws of supply and demand simply don’t apply to dense cities like New York, San Francisco ands Hong Kong, because new housing or upzoning might raise land prices.* After all (some people argue) Hong Kong is really dense and really expensive, so doesn’t that prove that dense places are always expensive? A recent paper by three Hong Kong scholars is quite relevant. They point out that housing supply in Hong Kong has grown sluggishly in recent years. They write that in the late 1980s, housing supply grew by 5 percent per year. But since 2009, housing supply has grown at a glacial pace. Between 2009 and 2015, housing supply typically grew by around 0.5 percent per year; in the past couple of years, it has grown by between 1 and 1.5 percent per year. The authors note that these numbers actually overstate supply growth, because they do not include housing that has been demolished. Not surprisingly, housing prices have grown more in recent years. In the 1980s, housing costs increased by roughly 1 percent per year; in the past decade, costs have risen by as much as 3 percent per year. (Figure 4d). Thus, Hong Kong data actually supports the view of many American scholars that housing prices tend to be highest in places where housing supply fails to grow. Why is supply stagnant? The authors point out that in Hong Kong, as in some U.S. cities, government limits housing density through floor area ratio regulations. And because Hong Kong land is government-owned, the local government can restrict housing supply by refusing to sell vacant land. Because high land costs mean more revenue for the government, government has an incentive to sell land slowly in order to keep land prices high. […]

Find the full-length report draft here. New York’s political community and the general public have yet to come to terms with reality on congestion pricing. While COVID-19 has suppressed travel demand across the region — deeply for now and to an uncertain extent over the next several years — that decrease has been concentrated in mass transit. Bridge and tunnel crossings into Manhattan are, as of this summer, only down 9% from the pre-COVID baseline. The average daytime travel speed in Manhattan below 60th Street is already back down to 8MPH, barely above the pre-COVID average of 6.9MPH. As the recovery continues, traffic will only get worse — and we need a flexible and dynamic tolling regime that can “roll with the punches” of varying traffic and economic fluctuations as it permanently solves the congestion problem. The paper offers four novel suggestions for congestion pricing in New York City: 1. A speed target should be at the center of policy, rather than revenue, and the fee should vary dynamically in response to traffic volumes to achieve the target speed subject to a maximum peak toll. (Subject to political constraints, the closer the peak toll cap can get to $26, the better the economically estimated balance of speed and toll price). 2. Upstream tolls should be credited broadly to increase regional equity and ensure the incentives to choose any given route to Manhattan depend only on traffic management, not on revenue considerations. 3. Dynamic tolls on each entry point to Manhattan should float independently to incentivize only useful “toll shopping”. Current toll differences on priced and unpriced crossings are arbitrary and divert traffic to the busiest free crossings, while independently floating tolls would equilibrate to balance traffic volumes across all crossings. 4. The cap on licenses for For-Hire Vehicles should be removed and […]

The Manhattan Institute, a conservative (by New York standards) think tank, recently published a survey of New York residents; a few items are of interest to urbanists. A few items struck me as interesting. One question (p.8) asked “If you could live anywhere, would you live…” in your current neighborhood, a different city neighborhood, the suburbs, or another metro area. Because of Manhattan’s high rents, high population density, and the drumbeat of media publicity about people leaving Manhattan, I would have thought that Manhattan had the highest percentage of people wanting to leave. In fact, the opposite is the case. Only 29 percent of Manhattanites were interested in leaving New York City. By contrast, 36 percent of Brooklynites, and 40-50 percent of residents in the other three outer boroughs, preferred a suburb or different region. Only 23 percent of Bronx residents were interested in staying in their current neighborhood, as opposed to 48 percent of Manhattanites and between 34 and 37 percent of residents of the other three boroughs. Manhattan is the most dense, transit-dependent borough- and yet it seems to have the most staying power. So this tells me that people really value the advantages of density, even after months of COVID-19 shutdowns and anti-city media propaganda. Conversely, Staten Island, the most suburban borough, doesn’t seem all that popular with its residents, who are no more eager to stay than those of Queens or Brooklyn. Having said that, there’s a lot that this question doesn’t tell us. Because no identical poll has been conducted in the past, we don’t know if this data represents anything unusual. Would Manhattan’s edge over the outer boroughs have been equally true a year ago? Ten years ago? I don’t know. Another question asked people to rate ten facets of life in New York […]

I just read a 2018 book by a variety of authors (most notably Jonathan Levine, author of Zoned Out), From Mobility to Accessibility: Transforming Urban Transportation and Land Use Planning. The key point of the book is that rather than focusing solely on “mobility”, planners should focus on “accessibility”. What’s the difference? The authors describe mobility as speed or the absence of congestion; thus, a new highway that saves suburban commuters a few seconds increases mobility. “Accessibility” means making it easy for people to reach as many major destinations as possible, regardless of the mode of transport. For example, allowing more housing near downtowns and other urban job centers increases accessibility because it makes it easier for more people to live near work. However, residents of these neighborhoods might oppose such housing based on concerns about mobility; that is, they might fear that new neighbors might reduce mobility by increasing traffic. Obviously, an emphasis on increasing accessibility favors more compact development: people benefit from living closer to work, even if they are not driving 80 miles an hour. It also seems to me that the emphasis on accessibility favors more market-oriented land use policies; in the absence of government control, landowners will naturally want to increase accessibility by building housing near job centers and vice versa.

In my email box today, I received a message from an anti-housing group, touting a study from the localize.city website* on sunlight on New York neighborhoods. The purpose of the study is to show which neighborhoods have the least sunlight. The study found that 27 of the city’s allegedly darkest neighborhoods are in Manhattan. More interestingly, the list of most sunlight-deprived Manhattan neighborhoods includes some of the city’s richest areas: Midtown, the Financial District, Tribeca, Upper East Side, and the Upper West Side. By contrast, the list of Manhattan’s ten sunniest areas include not only a few well off areas (like Hudson Yards and Battery Park City) but less pricey areas like Marble Hill and Inwood. Why does this matter? My interpretation of these facts is that people who can afford to live anywhere don’t really care very much about an extra hour or two of sunlight, which in turn suggests that sunlight is basically just an excuse to block new housing rather than something people actually care about in other contexts. To put the matter another way, New Yorkers may actually value shade over sunlight, if they care about the issue at all. *I note that if you really do care about sunlight more than I am suggesting that most people do, you can search an individual address at the Localize website.

One common leftist argument against new housing is the “Red Vienna” argument: the claim that housing can only be affordable in places where the government dominates the housing market. Supporters of this claim like to mention Vienna, where (according to progressive lore) Big Brother builds lots and lots of super-affordable public housing, while the Big Bad Market is not involved. But a recent article about Vienna states that “one-third of the 13,000 new apartments built in Vienna each year are funded by the government and commissioned by the housing associations.” This means that about 8700 apartments are built every year by the private sector. In a city with 1.8 million people, that’s a lot. By contrast, in Manhattan (which has a comparable population) about 3000 housing units were built between 2014 and 2017- far less than Vienna. Even in Houston (which has a slightly bigger population) only 14,653 housing units of all types, or about 3700 per year, were built between 2014 and 2017. In other words, even if not a single unit of public housing had not been built, Vienna would still have built more than twice as many units as high-growth Houston, and about ten times as many as Manhattan. Vienna’s affordability is thus an argument in favor of lots more housing, not an argument in favor of NIMBYism.

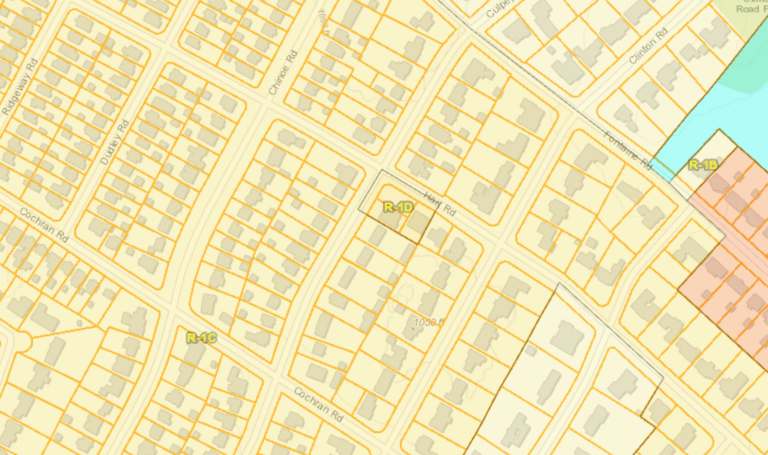

As zoning has become more restrictive over time, the need for “safety valve” mechanisms—which give developers flexibility within standard zoning rules—has grown exponentially. U.S. zoning officially has two such regulatory relief mechanisms: variances and special permits. Variances generally provide flexibility on bulk rules (e.g. setbacks, lot sizes) in exceptional cases where following the rules would entail “undue hardship.” Special permits (also called “conditional use permits”) generally provide flexibility on use rules in cases where otherwise undesirable uses may be appropriate or where their impacts can be mitigated. An extreme grade change is one reason why a lot might receive a variance, as enforcing the standard setback rules could make development impossible. Parking garages commonly require special use permits, since they can generate large negative externalities if poorly designed. Common conditions for permit approval include landscaping or siting the entrance in a way that minimizes congestion. (Wikipedia/Steve Morgan) In addition to these traditional, formal options, there’s a third, informal relief mechanism: spot zoning. This is the practice of changing the zoning map for an individual lot, redistricting it into another existing zone. Spot zonings are typically administered where the present zoning is unreasonable, but the conditions needed for a variance, special permit, or a full neighborhood rezoning aren’t. In many states, spot zonings are technically illegal. The thinking is that they are arbitrary in that they treat similarly situated lots differently. But in practice, many planning offices tolerate them, usually bundling in a few nearby similarly situated lots to avoid legal challenge. An example of a spot zoning. Variances, special permits, and spot zonings are generally considered to be the standard outlets for relief from zoning. But there’s a fourth mechanism that, to my knowledge, hasn’t been recognized: let’s call it the “spot text amendment.” Like spot zonings, spot text amendments […]

While reading someone else’s work, I recently ran across an article by David Cay Johnston of the New York Times, claiming that overseas oligarchs turning apartments all over the world into unused “ghost apartments”. In this article, Johnston writes: “In Paris, for instance, one apartment in four sits empty most of the time.” This claim struck me as so astonishing that as to be implausible, for the simple reason that in other “global” cities vacancy rates are much lower. For example, in New York only 9 percent of housing units are vacant, and most of those units are currently for sale or rent.* Even this vacancy level should not be particularly astonishing, since cheaper American cities often have higher vacancy rates. For example, Houston has an 11 percent vacancy rate, and Atlanta has an 18 percent vacancy rate. After googling “one in four paris apartments vacant” I found an article claiming that 26 percent of apartments in four Paris arrondisements (neighborhoods) is vacant- a much narrower claim, comparable to an assertion that one in four midtown Manhattan apartments is vacant. One would think that a journalist as distinguished as Johnston would know the difference between “Paris” and “some parts of Paris.” A more recent article claims that only 7.5 percent of Paris apartments are vacant- a lower vacancy rate than that of New York. Moreover, we don’t know what the local media means by “vacant.” Does this category limited to apartments that are unused 365 days a year? What about units that are rented out now and then through Airbnb? Or units that are currently being advertised for rent or sale? I suspect that the true number of “ghost apartments” is far lower than 7.5 percent, since in London (another “global city”) less than 1 percent of housing units are […]

Five years ago everything in California felt like a giant (land use policy) dumpster fire. Fast forward to today we live in a completely different world. Yimby activists have pushed policy, swayed elections, and dramatically shifted the overton window on California housing policy. And through this process of pushing change, Yimbyism itself has evolved as well. Learning by Listening Yimbys started out with a straightforward diagnosis of the housing crisis in California. They said, “…housing prices are high because there’s not enough housing and if we want lower prices, we need more housing”. And they were, of course, completely right…at least with regards to the specific problem-space defined by supply, demand, and the long run. As Yimby’s started coalition building, though, they began recognizing related, but fundamentally different concerns. For anti-displacement activists, the problem was not defined by long-run aggregate prices. It was instead all about the immediate plight of economically vulnerable communities. Increasing supply was not an attractive proposal because of the long time horizons (years, decades) and ambiguous benefit for their specific constituencies. Yimbyism as Practical Politics Leaders in the Yimby movement could have thrown up their hands and walked away. But they didn’t. Instead they listened and developed a yes and approach. The Yimby platform still embraces the idea that, long run, we need to build more housing, but it now also supports measures to protect those who’ll fall off the housing ladder tomorrow without a helping hand today. Scott Weiner’s SB50 is a great example of this attitude in action. If passed, the bill will reduce restrictions on housing construction across the state. It targets transit and job rich areas and builds in eviction protections to guard against displacement. At a high level, it sets up the playing field so that renters in a four story […]