Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

WASHINGTON – David Paitsel, 42, a former FBI agent, and Brian Bailey, 53, a D.C. real estate developer were sentenced today on bribery and conspiracy charges for their role in schemes involving confidential information held by the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development United States Attorney’s office There are plenty of housing laws you can break. But these grifters were busted only for bribing a city official for information. Otherwise, they used the housing law – the most innocent-sounding of all housing laws – correctly. Washington DC has a strong Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA). When a landlord sells, tenants have the right to match any offer, conceivably buying their own building. That never happens. But TOPA also allows tenants to sell their rights to literally anyone else. The law treats the new owner of the TOPA rights with the same exaggerated deference as a tenant. The TOPA grift goes like this: A TOPA shark, like Paitsel and Bailey, approaches tenants whose building is on the market. The “approach”, as I’ve witnessed it, can be a hand-scrawled note placed in the tenants doors or mailboxes. The tenants rarely know the mechanics of buying a house, let alone utilizing an obscure city-specific TOPA scheme that would have to involve collective action among many tenants. So the sharks offer the tenants a few hundred dollars for their rights. If the offer is accepted, the shark informs the landlord. Now suppose a prospective buyer comes along and offers $1,200,000 for a D.C. sixplex. The landlord must inform the shark, who now has the right to match any bona fide offer on the property. But the shark has no interest in buying – he just demands ten or twenty thousand dollars to surrender the rights. If the landlord resists extortion, the shark […]

Since 1973, the US Census Bureau has administered the American Housing Survey (AHS) in odd-numbered years. Surveyors ask questions about the quality and value of respondents’ housing, and have a battery of questions for the subset of respondents who moved recently, asking about their search process. The AHS regularly adds new questions and rephrases old ones from year to year. In 2021, they rolled out a group of three new questions. One asks recent movers whether they spent more or less than a month searching for their new home. This is the AHS’s first-ever variable dealing with search time. The other two, which are similar to questions asked in previous years, ask about search scope: whether respondents looked for housing in neighborhoods besides the one they ended up moving to, and whether they looked at other housing units in the same neighborhood they moved to. In analyzing these new questions within the largest 15 metro areas in the US, I found a curious and hard-to-explain relationship. Search time – the binary variable of taking more or less than a month to look for a home – seems to be predicted by the population of a metropolitan area (with r=0.57 and p > |t| = 0.026), whereas search scope in the sense of looking at multiple neighborhoods or multiple units within a neighborhood seems to be predicted by the cost of housing as gathered from 2021 Zillow data (for looking at multiple neighborhoods, r=0.65 and p > |t| = 0.009; for looking at multiple units, r=0.68 and p > |t| = 0.007). The inverse set of relationships are much weaker. Price and likelihood of taking over a month to search are positively correlated, but the relationship is not statistically significant; the same is true of the relationship between metro population and […]

Update 11/20: Chang-Tai Hsieh counters that Greaney’s critique ignores general equilibrium effects which make labor scale invariant. That doesn’t address the alleged coding errors. We’ll see – and perhaps I wrote an autopsy too early. Thanks to Bryan Caplan for getting Hsieh’s response out to the world. Popular urban econ should be shaken with the revelation that its most famous academic paper had two coding errors, a serious theoretical flaw, and a hypothesized mechanism that – when executed correctly – did not work at all. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti’s paper Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation noted that “high productivity cities like New York and the San Francisco Bay Area have adopted stringent restrictions to new housing supply, effectively limiting the number of workers who have access to such high productivity” – and used a simple model to estimate how much US growth could have been unlocked by decreasing those restrictions. Brian Greaney, an assistant professor at the University of Washington, released notes on his replication of The paper gained widespread notice as a 2015 NBER working paper and was published in 2019 in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. The paper already has an impressive 813 scholarly citations. But the paper has problems – fatal problems – and is embarrassingly sloppy. The embarrassment extends beyond the authors to the many referees and editors who missed surface, implementation, architectural, and foundational problems over a four-year period of peer review and discussion. Surface Greaney is not the first to find a mistake in Hsieh & Moretti. Bryan Caplan caught a major inconsistency in 2021, one that readers (myself included) and referees should have caught earlier. The authors reported huge annual effects adding up to a merely-large effects over 45 years. He noted a few other arithmetical mistakes and generously concluded, “authors and referees […]

Tyler is stirring the pot over at Marginal Revolution, asking whether Tokyo’s low rents are a YIMBY success or just a productivity failure: low productivity and low immigration keep demand down. He calls the latter “NIMBYism”. That framing doesn’t hold up very well, but we can discard it and think about the substance of the question. If we were totally ignorant of policy, what would we expect? Alonso-Muth-Mills models say prices should be higher in larger cities, and Tokyo is the largest city in the world. Most people think that price/income is the right way to compare home prices across countries, although price/construction cost might be better if we could accurately measure the latter. Let’s at least clarify the factual issues. Are Tokyo wages low? Japan wages are quite low by developed-world standards. Tokyo is perhaps 22% above the national average, about half of the New York/USA markup. The Alonso-Muth-Mills model says the largest city should be so because its wages are highest. Obviously, that assumes free movement of people. It’s not a mystery why Karachi is larger than Austin. But then why is Tyler criticizing Japan for low immigration? Clearly Japanese people should emigrate, like wage peer Spaniards and Poles. Is Tokyo cheap? Only relatively. I asked ChatGPT for a comparative list, but it wouldn’t even try. The best comparison I could find was in Demographia’s affordability yearbooks. They last included Japan in 2018 because of data reliability issues, so ymmv. But a Japanese PDFsays that Metropolitan Tokyo’s price-income ratio was 7.16 in 2016; in Tokyo Prefecture (the core) it was 9. Who knows how the definitions differ? All sources agree that Japanese home prices have risen less than most of the world in the pandemic era, so current data would favor Tokyo more. Tyler’s claim that Japan’s “brand […]

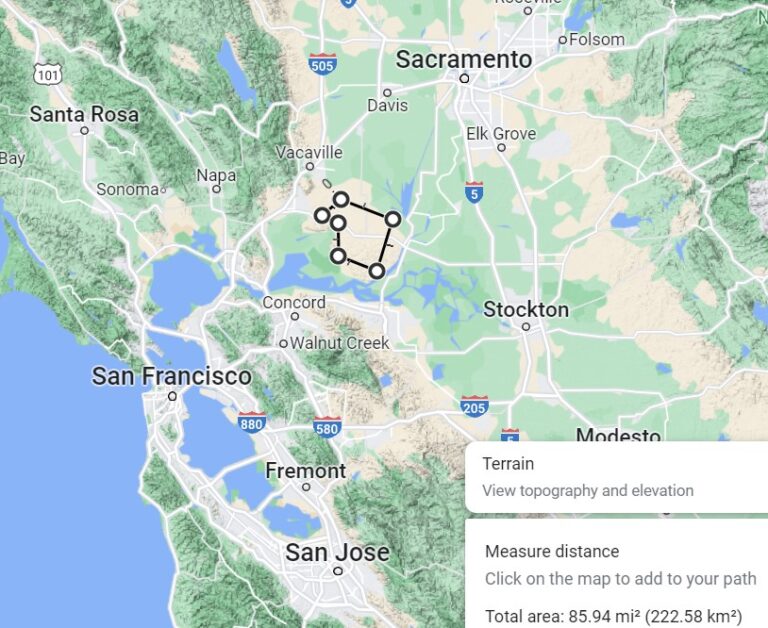

Conor Dougherty and Erin Griffith revealed the identities behind a Silicon Valley investor group, Flannery Associates, that had gradually purchased 55,000 acres of ranchland near Travis Air Force Base in Solano County, California. Scale check: that’s a lot of land. San Francisco is 30,000 acres; San Jose is 116,000. Earlier WSJ reporting includes a map of Flannery’s holdings, which are predictably a bit scattered. To zoom out and give a scale comparison, I outlined a 55,000 acre contiguous blob around the core of the Flannery holdings. At the density of nearby Vacaville, this much land would be home to nearly 300,000 people. If it matched Oakland, it would be more than twice that. Many, especially at the Charter Cities Institute, have written about new cities. But can a new city ever be truly “market urbanist”? Or is the intent to create a city necessarily an exercise in centralized planning? Monopoly Bizarrely, the one actor who could most purely create a market-driven city is the government: It could use eminent domain to assemble only the land needed for new infrastructure, tax all landowners fairly, and allow competition among landowners to compete via development and land use. At the opposite extreme, when a profit-maximizing private actor owns all the land, it faces a unique form of the monopolist’s tradeoff: The longer it holds onto land, the higher price it can charge on sale, but the less that land contributes to urban growth. One way to sidestep this tradeoff is for the monopolist to develop land itself. But of course that concentrates risk, and the cost of development is at least a hundred times more than the land cost (which appears to have averaged about $16,000 per acre in Solano County). Zero to one So what’s a mega-landowner to do? I’d start by […]

“Renting in Providence puts city councilors in precarious situations.” That was the Providence Journal’s leading headline a few days ago, as the legislature waited for Governor Daniel McKee to sign a pile of housing-related bills (Update: He signed them all). Rhode Island doesn’t have a superstar city to garner headlines, but it’s housing costs have mounted as growth has crawled to a standstill. But unlike in Montana and Washington, Rhode Island’s were largely procedural, aiming to lubricate the the gears of its existing institutions rather than directly preempting local regulations. House Speaker Joseph Shekarchi (D-Warwick), who championed the reforms, clearly drew on his professional expertise as a zoning attorney to identify areas for procedural streamlining. Specific and objective Six bills transmitted to the governor cover the general rules affecting most Rhode Island zoning procedures: S 1032 makes it easier to acquire discretionary development permission. Municipalities cannot enforce regulations that make it near-impossible to build on legacy lots that do not meet current regulatory standards. Municipalities can more quickly issue variances and modifications. (Rhode Island draws a unique distinction between minor and substantial variances, labeling the former “modifications” and subjecting them to a simpler process. A substantial variance must go before a board for approval; a modification can be approved administratively unless a neighbor objects. Municipalities must issue “specific and objective” criteria for “special use permits”, otherwise those use are automatically allowed as of right. That phrase – specific and objective – shows up again and again in Speaker Shekarchi’s bills. S 1033 requires that zoning be updated to match a municipality’s own Comprehensive Plan within 18 months of a new plan’s adoption. It also requires an annually updated “strategic plan” for each municipality, although the content and legal force of the strategic plans are unclear to me. S 1034 broadly […]

One common NIMBY* argument is that new housing (or the wrong kind of new housing) will “destroy the neighborhood.” For example, one suburban town’s politicians fought zoning reform in New York by claiming that allowing multifamily housing “is a direct assault on the suburbs.“ Indeed, many people do seem to believe that apartments and houses are somehow incompatible. But I saw an interesting counterexample recently. A couple of weeks ago, I attended the CNU (Congress for the New Urbanism) conference in Charlotte, North Carolina. CNU usually sponsors neighborhood tours, and I toured Myers Park, one of the city’s richest neighborhoods. Myers Park was built in the 1910s; most blocks are dominated by large single-family houses with an enormous tree canopy. Although Myers Park is only a couple of miles from downtown Charlotte, it certainly looks suburban, if by “suburban” you mean low-density and dominated by houses. (According to city-data.com, the neighborhood density is just below 4000 people per square mile, less than that of affluent Long Island suburbs like Great Neck and Cedarhurst). And yet on one of the neighborhood’s major streets (Queens Road) apartments and houses seemed to alternate. This does not seem to have reduced home values; the average value of detached homes there is over $1 million, about four times the statewide average. Moreover, Myers Park apartments are not the sort of “missing middle” housing that is virtually indistinguishable from a house. I saw a five-story building in Myers Park: not a skyscraper but definitely not something that looks like its neighbors. Not far away is a four-story building that looks like it has a few dozen units. In other words, apartments and houses can coexist, even in places that are very suburban in many ways. *As many readers of this blog probably know, NIMBY is an […]

In a recent Mackinac Policy conference, Detroit’s Mayor Mike Dugan proposed *drum roll* a land value tax. Sort of. Mayor Dugan’s proposal would create separate tax rates for land and capital improvements (i.e. the buildings on top). Specifically, he wants to decrease the tax rate on buildings by ~30% and increase rates on land by ~300%. The change would increase revenue for the city and also cause a series of second order effects. Taxing Blight & Rewarding Investment Detroit’s existing tax structure disincentives development. Holding vacant land or land with dilapidated (i.e. assessed as worthless) structures is cheap from a tax perspective. Actually developing land triggers a tax increase because of the brand new structure who’s value gets figured into the tax bill. What’s worse, the existing tax system encourages land hoarding. Land speculators sit on neglected parcels on the off chance that a developer needs it as part of a larger project. To caveat that, though, not all land speculation is bad. Holding some land off market and releasing it later into a development cycle can have positive benefits. In Detroit’s case, however, these are mostly vacant lots and abandoned buildings creating public health hazards the city has to deal with. The Political Economy of Land Value Taxation Unexpectedly – for me as a latte sipping coastal urbanite in California – Dugan’s LVT would also lower tax bills for homeowners. Land values in Detroit are low — in absolute terms and relative to structure values. Making the shift to taxing the less valuable land component of a property nets out positive for most homeowners. And the fact that it’s a win for homeowners makes me think it’s politically viable, both in Detroit and elsewhere. In places struggling to get back on a growth footing — places where land values […]

In a pair of posts, Scott Alexander goads his mostly-YIMBY readers by claiming to believe that density is likely to increase prices. To quantify his readers’ views, he laid out a thought experiment in a Google poll, the results of which we’ll no doubt see in a few days. You can see the poll – and my answer – below. As a YIMBY scholar, I mood-affiliate with the first answer, but I chose the middle one because there is a fundamental misunderstanding between pro-housing people like me and Scott’s recent posts. Housing growth is not the same as city densification Scott’s experiment isn’t a “housing growth” experiment, it’s a “city densification” experiment. Crucially, he requires “proportional increases in the number of office buildings, schools, etc”. That is, the experiment would increase office space at the same pace as housing even though office vacancy rates (19%) are far higher than housing vacancy rates (~1.7%). Oakland is a pretty balanced city: as best I can tell from simple Census data, it probably has a jobs/residents ratio pretty close to the California average (by contrast, San Francisco has twice the state jobs/resident ratio). If Scott ran his experiment in a bedroom community, or stipulated that office space is left under current regulations, I’d have an easy time coming down on the “less expensive” side of the ledger. The point of the YIMBY movement is that housing faces uniquely strict regulation. California cities (and those in some other states) believe that offices and industrial uses are “taxpayers”, generating more revenue than they use in services. Housing is viewed as a fiscal cost. Regulation (“fiscal zoning“) and discretionary decisions have reflected this bias for decades. The result is headlines like “SF added jobs eight times faster than housing since 2010.” If Oakland upzoned citywide, it […]

The Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley has released a policy brief summarizing the effect on housing production of the bewildering array of new housing laws California has enacted since 2016. A preliminary analysis of market effects of the new laws, accompanied by findings from interviews with California-based planners and land use lawyers, points toward the effectiveness of simple and direct legislation requiring localities to give ministerial approval to small-scale projects. For other laws, including those prescribing more complex formulas regarding affordability criteria for larger developments, it remains too early to gauge how housing production will respond. Of the legislation that has been enacted to date, California’s accessory dwelling unit laws (beginning with SB 1069 in 2016), according to those interviewed by the Terner Center, have been responsible for the astonishing twenty-fold increase in ADU permits documented from 2016 to 2021. Legislation enacted in 2021 requiring ministerial approval for duplexes and lot splits (SB 9), estimated by the Center to allow for up to 700,000 new units, has not yet been widely used, partly due to localities’ use of other restrictive zoning regulations such as mandatory setbacks to impede use of the law. Further strengthening of this law, in the same manner that the ADU law was fortified through 2019 revisions, may be necessary to unlock its full potential for new home construction. Other new laws are in the early stages of demonstrating their effectiveness. The imposition of stricter requirements on localities’ Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) process through legislation enacted in 2017 and 2018 has resulted in dramatic increases in zoning capacity targets for the next eight-year period set by the Housing Element Law (of which the RHNA is a part). For Southern California and the Bay Area, total housing allocation has increased from […]