Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

[This post was originally published on the blog Better Institutions] The people who live in coastal urban cities tend to be a pretty liberal bunch. We’re leading the country on minimum wage laws, paid sick leave, climate change mitigation, and a host of other important issues. We care deeply about equality of opportunity, and we’re willing to invest our time and money to advance that effort—even if the people we help don’t always look like us or come from the same neighborhood, state, or even country. I’m proud to count myself among their number. And then we turn to housing. Maybe it’s just because we’re doing great on so many other fronts, but when I look at our inability to solve the housing crisis in places like San Francisco, New York, and Washington, D.C., I’m left feeling nothing but depression and hopelessness. It’s all the more frustrating because unaffordable housing might be the most important economic problem facing residents of liberal U.S. cities, and we’re perfectly, comprehensively, and unmistakably blowing it. The causes of this failure are too numerous to ever fully enumerate in a single blog post, and, admittedly, some are out of the hands of cities themselves. But I don’t want to be too forgiving—state and federal policy plays a role, for example, but liberal U.S. cities are also typically located in liberal U.S. states, and federal policy applies equally to all, including the cities that have managed to remain affordable. There’s also the impact of global capitalism on a few world class cities, but it’s hard to feel genuine pity for places where foreign investors are willing to dump billions of dollars. Boo-hoo. At it’s heart this is a problem of liberal governance and/or policy, and we need to face it head on. We can’t blame this on someone else. It’s our […]

Homeownership boosters use many arguments in favor of buying rather than renting, one of which is that purchasing a home is a key part of the path toward a lifetime of financial success. They often say that renters are helping landlords profit when they would be better off paying their own mortgage instead. But a more nuanced analysis shows that it’s possible both for landlords to profit and for renting to make more financial sense than buying for some people. Someone purchasing a property to rent out will be purchasing an investment rather than a home — an emotionally fraught purchase often fueled with American Dream mythology. Because of the large transaction costs in buying and selling houses, people tend to buy the home they foresee wanting for many years after the purchase date. A childless couple might purchase a four-bedroom home in a good school district for the future, meaning that they end up over-consuming housing for their yet unborn children. If this hypothetical couple decided to rent until their children were school-age instead, they would likely be able to save and invest a substantial amount by spending less on housing in the near term. Would a landlord purchase this couple’s single family dream home? Probably not. Rather, with the same money, he might purchase a small apartment building in a less desirable part of town. These differences in purchasing decisions help to explain why landlords can profit in the same cities where people may not come out ahead by buying instead of renting. In addition to having disparate motivations when purchasing property, a potential landlord likely has other comparative advantages that make him more likely to profit from real estate relative to the average homebuyer. He may have above-average knowledge of which neighborhoods are likely to see […]

[This piece was originally published on the site Better Institutions.] On March 7th, Los Angeles is going to vote on the type of city it wants to be. The vote will be over Measure S, formerly known as the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative (NII), which seeks to limit housing development in the city. Backers of the initiative claim that City Council is too beholden to developers, and that the pace of new housing and commercial development in the city is out of control. They also express concern that “mega projects” are making Los Angeles less affordable, since few new homes are being targeted at low and moderate income households. It’s a really bad plan, but calling Measure S “bad” doesn’t go nearly far enough. It is, in fact, the Donald Trump of ballot initiatives. It’s a cynical effort to co-opt a legitimate sense of frustration—frustration felt by those who haven’t shared in the gains of an increasingly bifurcated society—and to use that rage and desperation for purely selfish purposes. It invites us to vent our frustrations and, in so doing, to further enrich those who helped to engineer our ill fortune. And as with Trump, a Measure S victory will roll back the clock on years of steady progress. Since I think there are a lot of folks out there who genuinely haven’t made up their minds about the initiative, or aren’t yet familiar with it, I’d like to summarize some of the most important reasons to oppose it when it comes time to vote this March. 1. IT WILL MEAN FEWER AFFORDABLE HOUSING UNITS FOR LOW INCOME HOUSEHOLDS. The Coalition to Preserve LA, which is backing the initiative, is turning this into a referendum on housing development in Los Angeles. They’re arguing that new homes have “wiped out thousands of […]

[This article, originally published on the site Tech for Housing, has been updated. Mai-Cutler’s kickstarter has a few days left. You can donate here.] How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained) is Kim Mai-Cutler’s 2014 TechCrunch masterpiece exploring the history of Bay Area land use policy. It was the first investigatory piece to thoroughly survey the political, economic, and historical precursors of today’s housing crisis. And in explaining the problems that plague San Francisco, it provided the intellectual spark for nearly two years of grass roots organizing and advocacy. And now there’s a kickstarter to turn it into a comic book. As it stands, the kickstarter has raised over 16K in pledges (I personally pledged $100 last week). This total means a professional artist can work on the project full time and produce a finished product come March. Turning KMC’s tome on Bay Area land use into a graphic novel might seem a frivolous use of resources to some, but let me tell you why this is actually important. Burrowing Owls is the seminal work on Bay Are Housing. It’s also over 10,000 words long. That means that as good as it is, there was only going to be a small audience of wonkish individuals that would ever be able to wade through the entire thing. Translating the article’s information, ideas and arguments into a visually consumable format, however, makes it accessible to a much larger group of people. For every person that read the original article, there are probably fifty who would thumb through the comic book if left out on your coffee table. So if you’ve got a few bucks, please consider making a pledge. And after that, pass the message along. Ideas matter, but so do the ways in which we choose […]

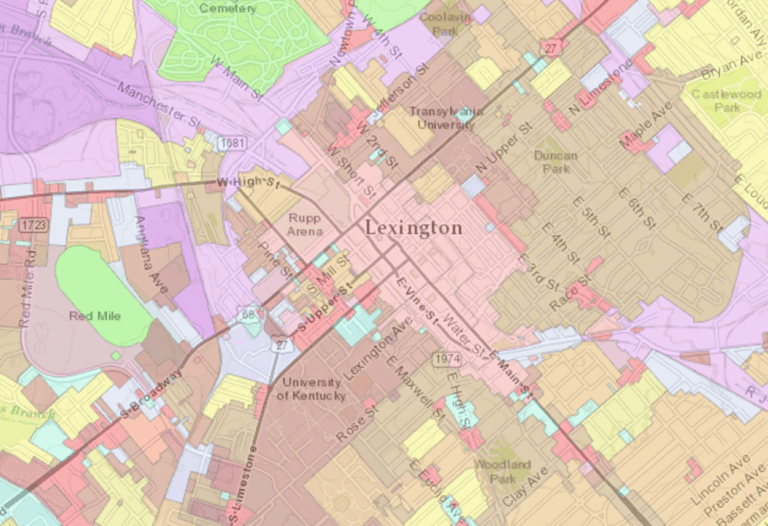

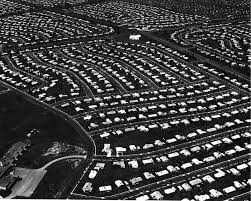

Lexington, Kentucky is a wonderful place, and that’s getting to be a problem. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the city: its urban amenities, thriving information economy, and unique local culture have brought in throngs of economic migrants from locales as exotic as Appalachia, Mexico, and the Rust Belt. The problem, rather, is that the city isn’t zoned to support this newfound attention. Over the past five years, the city has grown by an estimated 18,000 residents, putting Lexington’s population at approximately 314,488. Lexington has nearly tripled in size since 1970 and the trend shows no signs of stopping, with an estimated 100,000 new residents arriving by 2030. Despite this growth, new development has largely lagged behind: despite the boom in new residents, the city has only permitted the construction of 6,021 new housing units over the past five years—not an awful ratio when compared to a San Francisco, but still putting us firmly on the path toward shortages. The lion’s share of this new development has taken the form of new single-family houses on the periphery of town. Create your own infographics. Sources: ACS/Census Bureau At the risk of sounding like a broken record, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with single-family housing on the periphery of town. Yet in the case of Lexington, it’s suspect as a sustainable source of affordable housing. Lexington was the first American city to adopt an urban growth boundary (UGB), a now popular land-use regulation that limits outward urban expansion. As originally conceived, the UGB program isn’t such a bad idea: the city would simultaneously preserve nearby farmland and natural areas (especially important for Lexington, given our idyllic surrounding countryside) while easing restrictions on infill development. Create your own infographics. Source: Census Bureau The trouble with Lexington is that the city has undertaken […]

Because of work obligations, I listened to only about a third of today’s Cato Institute discussion on urban sprawl. I heard some of Randall O’Toole’s talk and some of the question-and-answer period. O’Toole said high housing prices don’t correlate with “zoning” just with “growth constraints.” But the cities with strict regionwide growth constraints aren’t necessarily high cost cities like New York and Boston, but mid-size, moderately expensive regions like Seattle and Portland. He says that if land use rules raise housing prices they violate the Fair Housing Act. Maybe this should be the case, but it isn’t. Government can still regulate in ways that raise housing prices, but just have to show reasonable justification for those policies under “disparate impact” doctrine. He also says cities would be less dense without zoning. Is he aware that most city regulations limit density rather than mandating density? O’Toole says growth constraints are why American home ownership rates are lower than in Third World countries and that the natural rate of home ownership is 75 percent. But why are home ownership rates so low in sprawling Sun Belt cities? For example, metro Houston’s home ownership rate is about 59 percent – higher than New York or San Francisco, but lower than Philadelphia or Pittsburgh. The highest home ownership rates are in Rust Belt regions like Akron, I suspect because of low levels of mobility. Some things he gets right: 1) public participation in land use process is harmful because it leads to more restrictions, not less; (2) the mortgage interest deduction doesn’t make much difference in home ownership rates.

Urban Institute Press • 2005 • 494 pages • $32.50 paperback In Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government, Robert H. Nelson effectively frames the discussion of what minimal government might look like in terms of personal choices based on local knowledge. He looks at the issue from the ground up rather than the top down. Nelson argues that while all levels of American government have been expanding since World War II, people have responded with a spontaneous and massive movement toward local governance. This has taken two main forms. The first is what he calls the “privatization of municipal zoning,” in which city zoning boards grant changes or exemptions to developers in exchange for cash payments or infrastructure improvements. “Zoning has steadily evolved in practice toward a collective private property right. Many municipalities now make zoning a saleable item by imposing large fees for approving zoning changes,” Nelson writes. In one sense, of course, this is simply developers openly buying back property rights that government had previously taken from the free market, and “privatization” may be the wrong word for it. For Nelson, however, it is superior to rigid land-use controls that would prevent investors from using property in the most productive way. Following Ronald Coase, Nelson evidently believes it is more important that a tradable property right exists than who owns it initially. The second spontaneous force toward local governance has been the expansion of private neighborhood associations and the like. According to the author, “By 2004, 18 percent—about 52 million Americans—lived in housing within a homeowner’s association, a condominium, or a cooperative, and very often these private communities were of neighborhood size.” Nelson views both as positive developments on the whole. They are, he argues, a manifestation of a growing disenchantment with the “scientific management” of […]

I was rereading the Obama Administration’s surprisingly market-oriented policy paper on zoning and affordable housing, and saw one good point that I had never really thought about. One common anti-development argument is that government should subsidize housing for the poor instead of allowing the construction of upper-class housing that might eventually filter down to the poor (or cause older middle-class housing to do so). The policy paper points out, however, that “HUD’s existing project-based and housing choice vouchers could serve more families if the per-unit cost wasn’t pushed higher and higher by rents rising in the face of barriers to new development.” In other words, high market rents make subsidies more expensive, which in turn means that government can subsidize fewer units with the same dollar. In other words, high market rents make it harder, not easier, for government to subsidize housing.

The University of Chicago Press has published a “definitive” edition of F. A. Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty under the editorial guidance of long-time Hayek scholar Ronald Hamowy. Given my interest in urban issues, it’s a good time for me to focus on chapter 22, “Housing and Town Planning.” It has several insights that I really like, but given the constraints of this column, for now I’ll talk about Hayek’s take on rent control. I must confess that it was several years after I became interested in the nature and significance of cities that I learned that Hayek had written anything on what we in the United States call “urban planning.” (Well, that’s not quite true; I did read The Constitution of Liberty as a graduate student, but in those days I didn’t appreciate how important cities are to both economic and intellectual development, so it evidently made no impression on me.) The analysis has a characteristically “Hayekian” flavor to it, by which I mean he goes beyond purely economic analysis and points out the psychological and sociological impact of certain urban policies that reinforce the dynamics of interventionism. The Economics of Rent Control Hayek’s economic analysis of rent control sounds familiar to modern students of political economy perhaps because it’s so widely (though not universally) accepted. This was hardly the case in 1960, when his book was first published. Hayek points out that despite the good intentions of those who support it, “any fixing of rents below the market price inevitably perpetuates the housing shortage.” That’s because at the artificially low rents the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. One effect of the chronic housing shortage that rent control produces is a drop in the rate at which apartments and flats would normally turn over. Instead, rent-controlled housing becomes […]

The Atlantic Magazine’s Citylab web page ran an interview with Joel Kotkin today. Kotkin seems to think we need more of something called “localism”, stating: “Growth of state control has become pretty extreme in California, and I think we’re going to see more of that in the country in general, where you have housing decisions that should be made at local level being made by the state and the federal level too. You have general erosion of local control.” In fact, land use decisions are generally made by local governments–which is why it is so hard to get new housing built. This is as true in California as it is anyplace else; when Gov. Brown tried to make it easier for developers to bypass local zoning so they can build new housing, the state legislature squashed him. Local zoning has become more restrictive over time, not less. And the fact that state government has added additional layers of regulation doesn’t change that reality. But did the Atlantic note this divergence from factual reality, or even ask him a follow-up question? No, sir. Shame on them!