Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Research shows that the implementation of an eviction moratorium significantly disadvantaged African Americans in the housing search process.

Just 1 in 25 new apartments is owner-occupied. What happened to building condos?

I’ve noticed numerous stories and tweets about a building boom: for example, a recent CNBC story asserts that the number of new apartments is “at a 50-year high.” Various twitterati have used this claim to support their own points of view: some claim that rents are stabilizing because of this new surge in supply, while others argue that the failure of rents to decline shows that new supply doesn’t reduce rents. But is supply really increasing that rapidly? Federal statistics on housing construction are at a Census housing data webpage. I looked at the “New Housing Units Completed” table and found that about 216,000 housing units in structures with over five units were completed in the first half of 2023. On the positive side, this is definitely an improvement over the 2010s, when the economy was still recovering from the 2008 recession. For example, in the first half of 2019, just over 169,000 such units were built, and 2018 was pretty similar. But is construction still up to Reagan-era levels? Not really. In the first half of 1986, almost 258,000 relevant units were completed. And in the first half of 1973, just over 378,000(!) such units were built. And these levels of construction were in a less populous country. Today the U.S. population is about 335 million, up from about 240 million in 1986 and 212 million in 1973. So if construction had kept up with population, our new unit count would be about 1/3 higher than in 1986, and almost 60 percent higher than in 1973. Instead, construction went down. To put the facts another way: our half-year multifamily construction rate is about 644 per one million Americans for 2023, down from 1075 per million in 1986 and 1783 per million in 1973. That’s not my idea of a […]

In recent years, I have thought of Herbert Hoover as sort of an urban policy villian, thanks to his promotion of zoning. But I recently ran across one of his memoirs in our school’s library. (Hoover’s memoirs were a multivolume set, and this particular volume related to his service as Secretary of Commerce and President). Hoover devotes less than a page zoning, noting that it was designed “to protect home owners from business and factory encroachment into residential areas.” He doesn’t mention the parts of zoning that have stunted housing supply in recent decades, such as the prohibition of apartments in homeowner zones, and minimum lot sizes. In fact, he brags about increases in housing construction when he was Secretary of Commerce, writing that “The period of 1922-28 showed an increase in detached homes and in better apartments unparalleled in American history prior to that time.” In particular, he notes that 449,000 dwelling units were built in 1921, and that this number rose to 753,000 in 1928. He claims some of the credit for this, primarily because the Commerce Department helped formulate a standard building code which he believed would be less costly than existing local codes, and because the Department sought to lower interest rates on second mortgages. One common argument against new housing is that because some new housing has been built, therefore there has been a building boom sufficient to meet demand. By contrast, Hoover was not a believer in the idea that any housing construction equals enough housing construction; he notes that “The normal minimum need of the country to replace worn-out or destroyed dwellings and to provide for increased population was estimated by the Department at 400,000-500,000 dwelling units per annum.”* *By the way you might be wondering how these numbers compare to current levels […]

In an encouraging post this morning, Matt Yglesias – one of the O.G. YIMBYs – summed up 10 years of success since his book, The Rent Is Too Damn High, was published. If you’d asked me, I’d have guessed that Too Damn High was published in 2015 or 2016, when YIMBY was in its infancy and researchers like me were starting to nose around zoning as a major regulatory cost. Yglesias was several years ahead of the curve. In his post, Yglesias gives free marketers a lot of credit for being for upzoning before it was cool. Market urbanists will certainly accept the compliment, and the legacies of Bernard Siegan and Bob Ellickson (1972…2022 – incredible!) are undeniable. But there’s another major part of the pre-YIMBY world that’s missing in this story, which is the progressive critics of suburban zoning. One of the graphs that keeps me up at night is the Google n-gram showing that “exclusionary zoning” was less a part of the discourse in the 2010s than it was throughout the 70s and 80s… and yet the activists of the time accomplished so little! The progressive critics of zoning, such as Paul Davidoff and Myron Orfield, were focused on allowing multifamily housing – especially if subsidized – in the suburbs. Urban housing markets were pretty slack at the time, and adding affordable housing in central cities risked concentrating poverty. A great book that covers a specific housing battle spanning the 1990s is Lawrence Lanahan’s The Lines Between Us. Alongside YIMBY As I understand it, these activists’ energy became formalized in the affordable housing industry. A lot of those institutions – and individuals – are still active. They have a mixed relationship with the YIMBY movement. In some cities and states, they’re enthusiastic participants. In others, they’re antagonistic. It […]

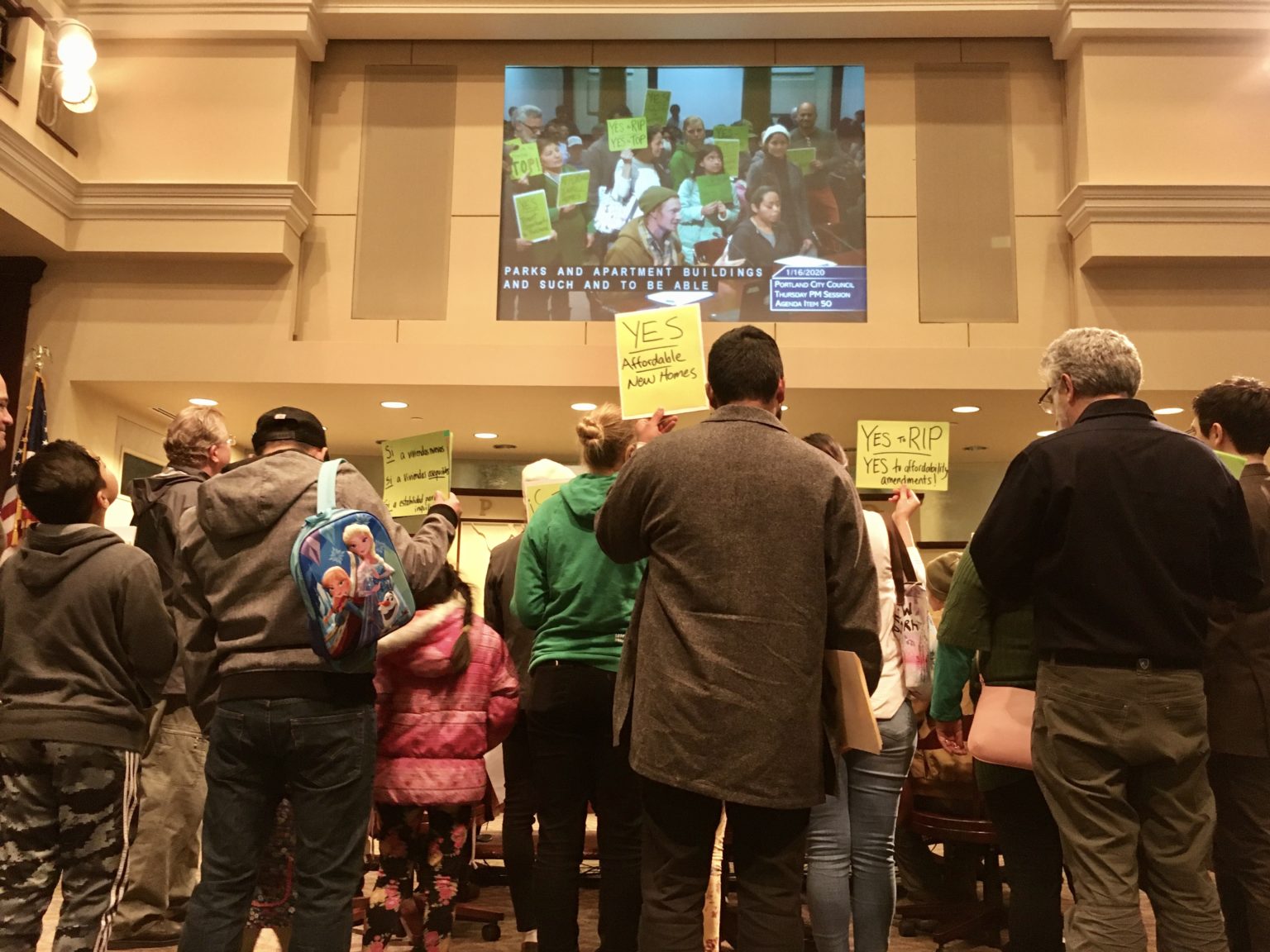

Case studies from several authors help explain the gritty politics of "Yes." The list includes three classics and will be expanded with reader submissions.

The best book on zoning and NIMBYism you’ve never read might well be The Housing Bias by Paul Boudreaux. The author is a law professor, but you’d be forgiven for thinking he’s a journalist. His writing is engaging – and occasionally funny – and he does what is unthinkable for many scholars: drives to various places to interview people who are engaged in the (legal) drama of what we now call “the housing crisis.” Boudreaux had the misfortune of being ahead of his time. The housing market was so soft in 2011 that his book landed with nary a sound. A quick web search turned up no book reviews besides the publisher’s blurbs. The book (and you’ll be forgiven if you stop reading right here) will set you back. That’s unfortunate. Just a few years later, the book would have connected with passions shared by the rapidly growing YIMBY movement and a publisher would have marketed it to the masses. Boudreaux’s thesis is that “the laws that govern our use of land are biased in favor of one specific group of Americans—affluent, home-owning families—who least need the government’s help.” He keeps his ideological cards close to the vest. But that’s the point: one need not lean left or right to want to stop using the power of the state to comfort the comfortable and afflict the afflicted. The first chapter is the most important, because it lays out the foundation for all that local governments do, good and bad, in land use: the police power. He’s writing from Manassas, Virginia, where “restaurants with Aztec pyramids on them” telegraph the large Hispanic immigrant community. A vocal minority opposed this local immigration, and pressured local governments to stop it. Of course, the city doesn’t issue passports, but the police power allows local […]

The Carnegie Library in Washington, D.C. is now home to the world’s newest Apple Store following an expensive rehabilitation funded by the retailer. Originally built as a public library in 1903, it reopened its doors to the public on May 11, 2019 following decades of disuse, neglect, and a slew of failed attempts to repurpose the building as a museum. While some are fretting that a historic building owned by the city has been turned over to commercial use, we can rest assured that the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., the current leaseholder to the building, made the right decision. More than fifteen years ago, Niskanen Center founder Jerry Taylor and his then-colleague at the Cato Institute, Peter Van Doren, had a novel proposal to solve an intractable political dispute about the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), a wilderness area in northeast Alaska that is home to large populations of wildlife and vast, untapped petroleum deposits. In the early 2000s, the Bush Administration proposed opening the refuge to oil drilling in the wake of rising crude oil prices. Naturally, the usual suspects came out in favor or against the proposal. Environmentalist detractors worried that a pristine wildlife area could be ruined by any drilling and the possibility of leaky pipelines. Advocates, on the other hand, claimed only a tiny sliver of land was needed to extract billions of dollars of oil and the refuge would remain largely untouched. The benefits of oil drilling, proponents argued, would be widely shared because oil is used in so many parts of economy. Taylor and Van Doren’s proposal was simple: the federal government should give ANWR, in its entirety, to the Sierra Club or some other environmentalist group, including full rights to use or transfer the land as they see fit. While the Sierra […]

It’s an understatement to say that zoning is a dry subject. But in a new video for the Institute for Humane Studies, Josh Oldham and Professor Sanford Ikeda (a regular contributor to this blog) manage to breath new life into this subject, accessibly explaining how zoning has transformed America’s cities. From housing affordability to mobility to economic and racial segregation to the Jacobs-Moses battle, they hit all the key notes in this succinct new video. If you need a go-to explainer video for the curious new urbanists, this is the one. Enjoy!

When I first became interested in urban planning, I believed a piece of professional mythology that went like this: “For all its faults, Euclidean zoning was a well-meaning effort to expand nuisance regulation in the face of the urban industrialization. It was later practitioners who used zoning for selfish and exclusionary purposes.” While not totally without basis, I now think this view is wrong. Today I would like to show how the iconic example of a nuisance that supposedly motivated Euclidean zoning—the Equitable Life Building in New York City—was in large part controversial because it threatened the interests of existing landlords. The Equitable Life Building at 120 Broadway was completed in 1915. A vanity project of an industrialist—Thomas Coleman duPont—as so many skyscrapers were and are, the projected stood 42-stories high across an entire block without setbacks, adding a startling one and a quarter million square feet of rentable office space to Lower Manhattan. Needless to say, some New Yorkers weren’t happy. But why? The conventional wisdom holds that the Equitable Life Building caused such a stir because it literally cast a shadow over the rest of the neighborhood. Indeed, the building cast a shadow stretching nearly a fifth of a mile across Broadway. But it wasn’t just the shadows that made the Equitable Life Building so uniquely audacious—after all, it wasn’t the tallest building in the neighborhood (this honor would go to the Woolworth Building, completed four years earlier 1912) and it wasn’t the first skyscraper to take up an entire city block without setbacks (by this point, the Flatiron Building was already an icon of the city). Rather, what made the project especially upsetting, on top of standard concerns about light and air, was that it was adding so much floor space at a time when the Lower […]