Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Welcome to the first post in Culture of Congestion! I’ll be posting quotes, ideas, and short essays relating to a book I’m writing, which I might describe as “What I have learned from the economic and social theory of Jane Jacobs.” My hope is to get thoughtful, informed feedback that will be useful in shaping the book. – Sandy Ikeda When I asked Jane Jacobs what she believed her main intellectual contribution was, she answered without hesitation, “Economic theory!” It’s been my experience that most of those who admire Jacobs for her trenchant writings and fierce activism against heavy handed urban planning and top-down urban design find it surprising that she thought of herself at heart as an economist. But a glance at the titles of her books makes this rather obvious: The Economy of Cities, Cities and the Wealth of Nations, and The Nature of Economies. And in her most famous book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she explains in intricate detail a la modern social theory what social institutions and norms enable people to discover and pursue their plans at street level, and how doing so allows the city in which they are embedded to flourish in unpredictable ways. She understood how creative innovation – in commerce, science and technology, and culture – is central to that flourishing. She explained, in a way that rivals or surpasses most economic theorists, how and under what conditions innovation takes place and how that tends to undermine attempts at central planning at the local level. One of my motivations for writing this book is to make Jane Jacobs, economist, better known especially to those who already rightly admire her for the other contributions she has made as a public intellectual, and to trace her criticisms of urban planning and design and of various public […]

Jane Jacobs’ writings span several disciplines—including ethics and most especially economics—but she is best known for her contributions to and her critique of urban planning, design, and policy. Many of those whom she influenced in academia, policy, and activism took the occasion of her one-hundredth birthday in 2016 to celebrate those contributions through lectures, biographies, and various events and publications. The current issue of COSMOS + TAXIS is offered in that same spirit. I am especially pleased that it includes the contributions of a diversity of scholars—with backgrounds in economics, urban policy, urban planning, geography, architectural history, and engineering—with a diversity of insights expressed from the perspectives of epistemology, intellectual history, spatial analysis, urban history, private cities, mercantilism, and of course spontaneous order; and ranging in approach from the theoretical to the historical to the applied. Indeed, we learn from Jacobs that from the diversity of the living city springs experiment, creativity, and surprise; and that pertains equally to the realm of living ideas. Read these pages and be surprised! Articles Special Issue on Jane Jacobs [pdf] Sanford Ikeda Jane Jacobs as Spontaneous Economic Order Methodologist: Part 1: Intellectual Apprenticeship [pdf] Pierre Desrochers and Joanna Szurmak Jane Jacobs as Spontaneous Economic Order Methodologist: Part 2: Metaphors and Methods [pdf] Joanna Szurmak and Pierre Desrochers Experimenting in Urban Self-organization: Framework-rules and emerging orders in Oosterwold [pdf] Stefano Cozzolino, Edwin Buitelaar, Stefano Moroni, and Niels Sorel Modern Cities as Spontaneous Orders [pdf] Wendell Cox and Peter Gordon NIMBYs as Mercantilists [pdf] Emily Hamilton A City Cannot be a Work of Art [pdf] Sanford Ikeda The State of Indian Cities [pdf] Shruti Rajagopalan The Kind of Problem Gentrification Is: The Case of New York [pdf] Francis Morrone Reviews The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans by Lawrence N. Powell[pdf] Leslie Marsh

My first article for TheFreemanOnline dealt with the “broken window fallacy.” But in the literature on social theory, there’s actually another important idea that also uses the metaphor of a “broken window.” In his comment on The Freeman’s Facebook page, Flavio Ortigao raised this point when he wrote: …I do not quite follow the putative analogy with broken windows theory. In many case[s] “broken windows” has been used as an analogy for the necessity of not allowing the degradation of public space/utilities. Inferring that there is a psychological effect that compounds the problem. I think [it] is very important that cities do not surrender to vandalism. This has little to do with the situation of Haiti, struck by a natural disaster. Mr. Ortigao is right. The idea to which he refers does not directly relate to the Haitian earthquake or to other situations in which destruction is supposed to create wealth. That’s a different “broken window.” The typical way to commit the broken-window fallacy is to argue that a natural disaster, war, or economic crisis is actually good for an economy. The idea is that if the event causes an increase in spending on infrastructure or war materiel or what-have-you, the “new” demand will stimulate the economy and create more wealth than there would have been otherwise. But that’s not what Mr. Ortigao is referring to. One of the articles I assign to my students is George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson’s “Broken Windows” (1982) in which they say: “…one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.” This would also apply to trash left on the sidewalk or drunks sleeping on benches, that sort of thing. And because “disorder and crimes are inextricably linked,” a community that tolerates minor […]

There are many ways to tell the story of urban-policy failure. Economists have shown how rent control creates housing shortages, sociologists how welfare programs destroy poor communities, and urbanologists how urban planning can debilitate cities. In his book The Future Once Happened Here, historian Fred Siegel has added a new and insightful chronicle of modern liberalism’s influence on social policy in New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles over the last 30 years. Siegel identifies racial tension as a main force that has driven urban policy since the 1960s. He lucidly and engagingly describes how that policy, informed by “riot ideology” based on liberal guilt and fear, transformed some major American cities from communities of tolerant strangers and great incubators of ethnic integration into rolling riots and sinkholes of federal largess. Associated with the riot ideology is what Siegel terms “dependent individualism,” the idea that each person has an absolute right to his “lifestyle,” at public expense and regardless of the consequences for social cooperation. Those consequences have been a “moral deregulation of public space,” which has eroded the trust that urbanologist Jane Jacobs identified as the lubricant that permits great cities to work well. The largest part of the book is devoted to New York City. Siegel explains how Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s success in getting federal aid from FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s set the pattern for fiscal irresponsibility in New York for the next five decades. Consequently, New York became dependent on an artificial, make-work economy, based on federally funded jobs and welfare bolstered by dependent individualism and the riot ideology. Nevertheless, its productive sector was still so large that both New York City and the state of New York have regularly sent more taxes to Washington than they have received in transfers. Surprisingly, supporters of […]

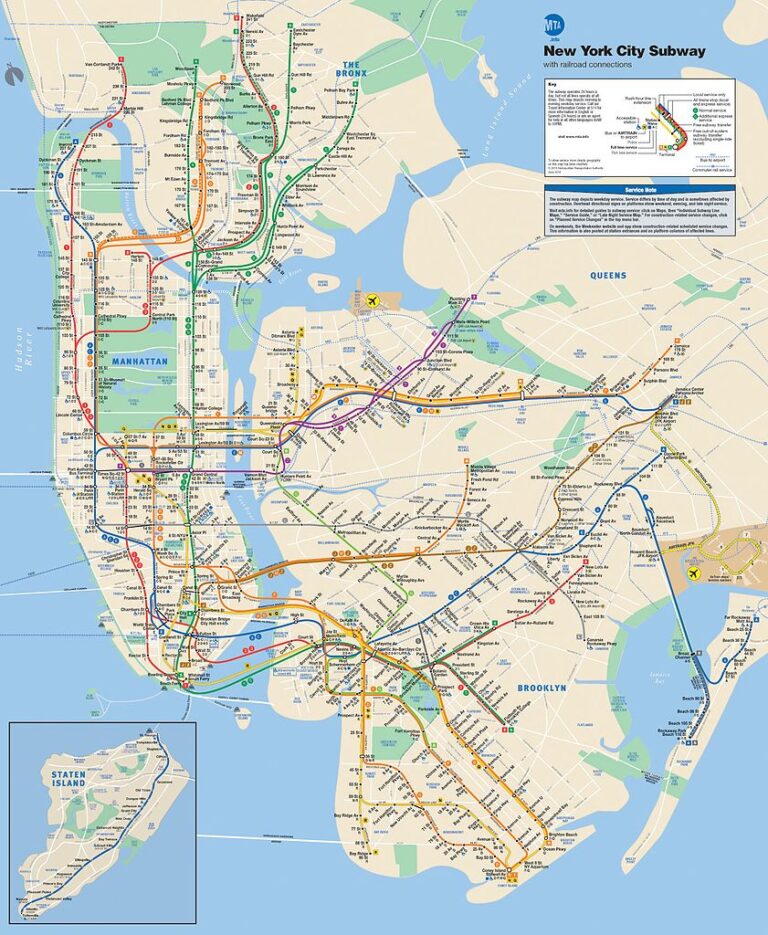

This year, for the first time since 1979, New York City has revamped its subway map. A quick glance shows a change in the background tinge from light tan to light green – most pleasant. To my relief, however, on closer inspection nothing essential has changed from the last version. Thank goodness it still doesn’t look anything like the map of London’s Underground. London’s map has been touted as the path-breaking paradigm of subway maps, the object of widespread acclaim and imitation. Indeed, most major cities’ transit systems have adopted the map’s efficient symmetry, which was created by Harry Beck back in 1931 during the heyday of high modernism. Here it is (pdf). It’s easy to see why it has won praise. It’s beautiful, looking like a two-dimensional version of a uranium molecule or the lattice of some fantastic crystal. The same could be said for the maps of the underground systems of Paris and Tokyo. It’s about Usefulness As you’ve probably already guessed, however, I don’t like it. And it’s not about aesthetics. Here’s the problem: I’m just one person, of course (although here’s another guy who seems to agree with me), but when I’m in London I find myself constantly frustrated when I try to get from place to place using that map. The problem is that I need two maps: the Underground map to tell me how to get from, say, Paddington to Notting Hill Gate, and a street map to tell me exactly where the heck Notting Hill Gate is in relation to Paddington. The former abstracts from so much street-level detail that, unless you’re already familiar with the layout of London, the map, rather increasing the efficiency of travel via mass transit, actually makes it more cumbersome. New York City’s subway map on the other […]

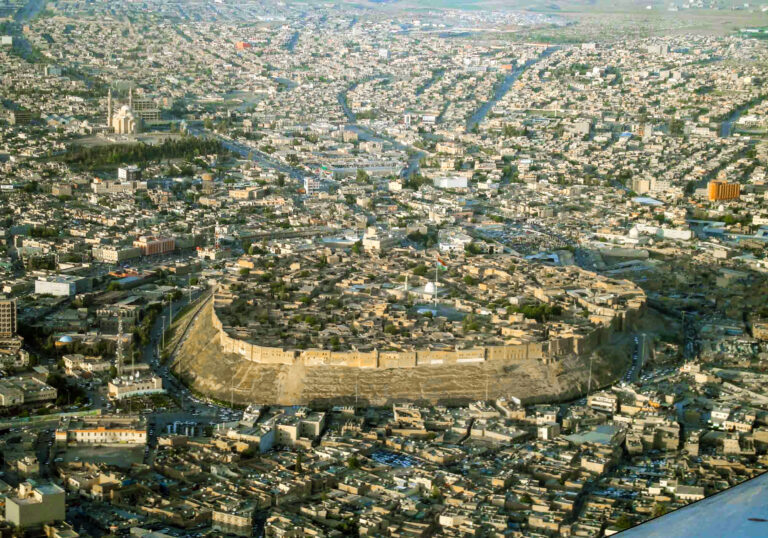

Four years ago my wife and I decided to take our son to a special and slightly unusual restaurant to celebrate his birthday. We were in Tokyo at the time and gave the taxi driver what we thought was the address for the restaurant – it had names and numbers on it. Cabbies in Tokyo, and in Japan in general, are renowned for their courtesy, the cleanliness of their cabs, and their driving skill. We were very surprised, therefore, when our driver suddenly pulled over and told us that “the restaurant is somewhere around here,” let us off, and drove away. After several minutes of search, we did manage to find the restaurant around the corner about a block or so away. We had a great meal, but the memory of that experience has always been something of a puzzle – until now. This summer we returned to Tokyo for a family vacation, and while relaxing in our hotel room I found myself thumbing through a guide book we had brought along, Japan Made Easy, in which I found this startling statement: “Tokyo … has thousands upon thousands of streets, but fewer than one hundred of them have names.” A quick check of Google Maps seems to confirm this assertion. (Hat tip to Jeremy Sapienza). More than One Way to Address a Letter This raises some obvious questions, such as how one addresses a letter. The guide says: …[T]he addressing system in Japan has nothing whatsoever to do with any street the house or building might be on or near. Addresses are based on areas rather than streets. In metropolitan areas the “address areas” start out with the city. Next comes the ku, or ward, then a smaller district called cho, and finally a still smaller section called banchi. This […]

As an economics professor, I often witness the surprise of my students when I explain how something as important as the market for food or clothing is self-regulating. True, there are quality and safety regulations that attempt to control potential hazards “around the edges” of these vital markets, but by far the heavy lifting is done by competition among rival firms in the same industry. Trying to sell tainted food or shoddy clothing in a competitive market without special privileges will either put you out of business or make you very quick on your feet. And I get great satisfaction when I see students realize that advertising, free entry, and entrepreneurship, in the context of economic freedom, are what keep goods and services safe, cheap, and of good quality. Witness what happens when drugs and prostitution are prohibited: overly concentrated, dangerously mixed narcotics and significantly higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases, both accompanied by violence and corruption. Here government intervention thwarts self-regulation. The Nonmarket Foundations of the Market Process In the past dozen years or so, as a result of my research interest in the economy of cities, which was sparked by my discovery of the writings of Jane Jacobs, I’ve come to appreciate more and more the nonmarket foundations of the market process. Some of this has been reflected in previous Wabi-sabi columns that were concerned with social networks (most recently last week but also here). Without norms that say, for example, treating strangers fairly and trading with them is good, or that lying to and stealing from strangers is bad, human well-being couldn’t have soared to the heights of the past 200 years, especially the last 60. Now obviously none of this would have happened either without the widespread acceptance of private property, freedom of association, and the […]

People in the American Midwest are said to be on average more conservative and more libertarian than people who live on the East and West Coasts. And that in turn is because people in rural areas are said to be more strongly tied to the traditions of individualism and self-reliance than those in big cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago—who politically are more statist and tend to see government as a first-responder to perceived economic and social problems. We could go back and forth arguing with conflicting evidence on urbanity and ideology that depend on, for example, whether you use “Republican” and “Democrat” as proxies for “right-wing” and “left-wing,” whether you’re comparing states or counties, and so on. So for the sake of argument I will concede that in today’s United States “urban” means statist and “rural” means conservative and libertarian. Does it follow then that people who live in dense cities are necessarily more statist than people who live in lower-density rural areas, exurbs, and suburbs? I think not. I believe the positive correlation between political conservatism and libertarianism and rural or “agricultural” living is an historical anomaly; that historically the countryside has been a great obstacle to liberty while cities have been the places where liberty and the fruits of liberty have flourished. (I place “agricultural” in quotation marks because only about 2 percent of Americans actually live on farms.) American Conservatism and the Libertarian Movement There are at least two meanings attached to the word “conservative.” The more general meaning refers to someone who has an above-average attachment to certain ideas and ways of living that are considered traditional. Now, few people like change as such and everyone has an attachment to at least some ideas of the past, whether conservative or liberal, libertarian or […]

Stanford economist Paul Romer has proposed an intriguing concept: the “charter city.” A charter city is a newly created city governed by a country other than the one within whose borders it exists. Its residents would remain citizens of the home country. Romer offers Hong Kong as an example when it was a British colony. According to the Charter Cities website: The two prerequisites for a charter city are uninhabited land and a charter granted and enforced by an existing government or collection of governments. With the right rules, a city will naturally grow as residents arrive, employers start firms, and investors build infrastructure and buildings. What makes a charter city attractive is the prospect of rapidly instituting rules consistent with economic development in an area that might otherwise take decades to do so, offering almost overnight the chance of a better life for the citizens of a impoverished country for whom long-distance immigration is too costly. Thus Romer has suggested that a charter city be established in Haiti for Haitians left homeless by the recent earthquake and who have little hope of help from an ineffective and otherwise corrupt Haitian government. (The Charter Cities site, however, says the time is not right for this option.) While I find myself largely sympathetic to the concept, two things bother me about it. Incentive Problems The first is whether it can overcome the Public Choice problem. Although the Hong Kong example is persuasive, I wonder whether the host country would really permit the guest country to bypass enough of its political and bureaucratic interests to establish an effective rule of law, free exchange, and other things necessary for long-term economic development. And once established, would the host permit enough free immigration from its own jurisdiction and the loss of long-established political bases […]

I sometimes ask myself if there is a “libertarian architecture” when thinking about what a purely libertarian culture — one that has been free from government intervention long enough to flourish — would look like. Not something I can answer in several hundred words, but let me begin. By “libertarian architecture” I don’t mean a particular style. In the absence of government intervention, however, I do think certain kinds of projects would be unlikely to emerge, and so it may be possible to rule out styles associated with such projects, from those of the Roman Forum to the Palm Islands of Dubai. My question may not seem so far-fetched to those who have read The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand’s influential novel about an uncompromising individualist architect, Howard Roark, who battles and defeats the forces of collectivism and conformity. For Roark/Rand individualist integrity means the radical rejection of traditional Palladian forms, the classical orders, and the aesthetics of the École des Beaux-Arts. Rand has Roark adopting a Frank Lloyd Wrightian, form-follows-function principle the product of which actually sounds like the hyper-modernism of le Corbusier, the architect whose (Euclidean) geometrical designs for entire cities, ironically, appeal more to the Cartesian rationality of collectivism than real human reason, which Michael Polanyi explains must actually rely tacitly on often inarticulable rules. But I don’t see why a libertarian architecture would necessarily reject traditional design. The Market Test Versus Liberating Wealth It seems that there are two somewhat contending forces to consider here. The first is the market test; the second the artistic freedom enabled by the wealth that markets create. Howard Roark’s survival depends on finding the right clients for his highly personal work, and at first there aren’t many of them. Tyler Cowen explains in In Praise of Commercial Culture that the reemergence of […]