Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Here’s something I hadn’t thought of in quite this way (but many others probably have): In a living city, space is cheap enough so that people with wacky (often “terrible”) new ideas can test them out, while wealthier people in that city search for wacky new things to try out (because they’ve experienced a lot of other things). In “creative” markets, such as for art, the demand side complements the supply side across income groups in an interesting way.

Viewing cities as spontaneous orders and not as works of art helps to explain the tradeoff between scale and order, as well as the role of time in softening the severity of that tradeoff. Complexity and creativity are at odds with scale and the comprehensiveness of design because increasing scale impinges on the action spaces where creative, informal contact tends to happen. Design might complement that informal contact to a point, but beyond a fairly low level it begins to overwhelm it. Again, small is not always beautiful, and big is sometimes unavoidable. That makes it all the more important to understand the impact of scale and design on spontaneous social orders. That applies as much to private as it does to public projects. When the designs are small relative to the surrounding social milieu, the downside of the tradeoff isn’t very steep. The problems start when budget constraints are soft and projects become mega-projects and mega-projects become giga-projects. I don’t want to sound too ideological – Jane Jacobs somehow avoided being ideologically pigeonholed all her life – but soft budget constraints are primarily the domain of governmental and, especially, of so-called public-private developments: Those elephantine-starchitectural-wonder-complexes that too-often strive for off-the-charts wow-factors. Without legal privileges, subsidies, and eminent domain, could the scale and degree of design of purely privately funded developments even begin to compare to those? I don’t think so. The rules of the game of urban processes interact in complex ways. So deliberately changing some of those rules to achieve a particular outcome is akin to trying to impose a particular design on the social order, killing the social order in the process, although perhaps preserving the appearance of life. Taxidermy again. (That, by the way, is why I have problems with landmarks preservation on the scale practiced […]

Before we can correct what we think is wrong with a city, we need an appropriate standard of what is right. That standard of rightness in turn depends on our understanding how the thing we are trying to fix is supposed to work. In this regard I’m afraid neither standard macroeconomics nor microeconomics is much help at all. In traditional macroeconomics, too much important detail is lost in its pre-occupation with aggregates and averages. For example, standard macroeconomic theory treats capital as homogeneous, and so makes no distinction between a hammer and a harbor, except that a harbor may be the equivalent of many, many hammers. Such an approach is too blunt an instrument for getting to the level of detail needed to appreciate the complex time-structure of capital of an economy, let alone to tell us what would be necessary to promote that structure (Lachmann 1978). Jacobs expressed antipathy toward macroeconomics. Macro-economics—large-scale economics—is the branch of learning entrusted with the theory and practice of understanding and fostering national and international economies. It is a shambles. Its undoing was the good fortune of having been believed in and acted upon in a big way (Jacobs 1984: 6-7) Earlier in this Chapter we saw that, unlike a living city, a nation-state is not a natural unit of economic analysis. In Jacobs’s words: Nations are political and military entities, and so are blocs of nations. But it doesn’t necessarily follow from this that they are also the basic, salient entities of economic life or that they are particularly useful for probing the mysteries of economic structure, the reasons for rise and decline of wealth. Indeed, the failure of national governments and blocs of nations to force economic life to do their bidding suggests some sort of essential irrelevance (Jacobs 1984: 31-32). The […]

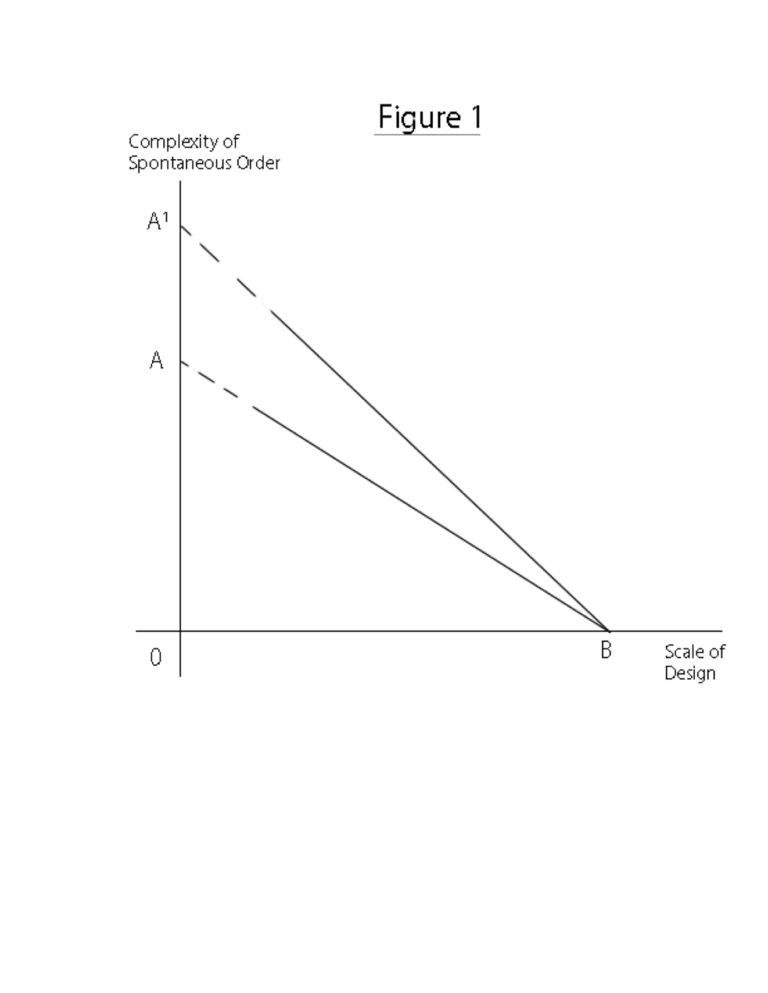

We can visualize the tradeoff between the scale of design and the complexity and spontaneity of a social order as a downward-sloping curve. A sort of “scale-versus-order-possibilities frontier.” In addition to scale and spontaneous order/complexity, a third element I would add to the tradeoff is the passage of time. You can to some extent plan for complementarity, but you can’t really plan for spontaneous complexity and intricacy. [Helpful to bring in capital theory here?] Fortunately, time allows people to some extent to adjust social networks and physical spaces to better complement their own plans, in ways that the designer could not foresee. That is, for any given scale, time lets people figure out novel uses for, or changes to, the space as originally designed. Those unthought-of uses constitute an increase in the level of complexity in a spontaneous order. Over time, then, the frontier can shift outward. Figure 1 reflects these relations: The scale of a structure and the designed or planned uses of the space within that structure are of course two different things. Increasing the dimensions of a room doesn’t necessarily mean the elements that go into its design become more complex. But to keep things simple, Figure 1 treats scale and design as highly positively correlated. [Is this necessary?] Thus, as scale increases so do the designed elements – you move from point A to point B – and together they decrease the potential for spontaneous order. [But think about the tradeoff between scale and order, keeping design constant. Just increasing scale does seem to increase the designed/planned element in a previously undesigned space.] Then, as time passes, the frontier shifts up from AB to A’B, where point B represents the case where the structure occupies100% of the relevant action space. So for any given scale, the […]

First of all, Jacobs observed that the artist abstracts from life, with all its “inclusiveness” and “literally endless intricacy.” Many architects, especially those with great ambition, seem to treat urban environments as merely a canvas for their works of genius, which if not already blank needs to be wiped clean before getting to work. The good ones at least try to take into account how their constructions fit or don’t fit into the existing built environment and how real people might actually use them. But whether you’re an architect or an economist, predicting how people will respond to a change is a pretty iffy thing. From my perspective that iffiness comes from two factors: complexity and radical ignorance. Complexity in this context means that the interactions among people are so numerous or varied or changeable that the costs of being aware of all of them is too high for anyone to calculate. Hayek defines the degree of complexity in terms of the “minimum number of elements of which an instance of the pattern consists in order to exhibit all the characteristic attributes of the class of patterns in question…” (Hayek 1964). In a world with only a few variables, such as those described in a high-school algebra problem, it is possible to have all the knowledge you need to get the correct answer. In the real world, however, the number of relevant variables is too large, that is the number of ever-changing interactions among people in society is so large, and our cognitive powers are too limited to do that. Compared to the vast complexity of the social order, predicting this week’s weather is a pretty simple matter. Radical ignorance means being unaware of information that would be relevant to making a decision, not because the cost is too high, […]

As Jacobs explains in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities: Artists, whatever their medium, make selections from the abounding materials of life, and organize these selections into works that are under the control of the artist…the essence of the process is disciplined, highly discriminatory selectivity from life. In relation to the inclusiveness and the literally endless intricacy of life, art is arbitrary, symbolic and abstracted…To approach a city, or even a city neighborhood, as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, is to make the mistake of attempting to substitute art for life. The results of such profound confusion between art and life are neither art nor life. They are taxidermy.” (1961: 372-3, emphasis original) So how do we avoid turning the results of urban design into taxidermy and killing off a city by planning? I think the short answer is that we avoid it by recognizing that there’s a tradeoff between the scale of a design and the degree of spontaneity, complexity, and intricacy in the resulting social order that the design allows. Now, saying that a city cannot be a work of art doesn’t mean of course that a city cannot be beautiful or that deliberate design can never enhance that beauty. But I am suggesting that beauty that is designed as a work of art is fundamentally different from the undersigned beauty that emerges from a lifetime of experience. The skillfully made-up face of a fashion model and the face of a 90-year-old grandmother are both beautiful, but in profoundly different ways. Niels Gron, quoted in Gerard Koeppel’s City of a Grid: How New York Became New York: Before I came to this country, and in all the time […]

One of the popular sports broadcasts I used to watch as a kid promised interviews with athletes that would bring them to you “up close and personal.” As I was once waiting in line to order coffee at one of my favorite local coffeehouses there were several people ahead of me. I followed the “barista” taking orders, with his dark-framed glasses, reddish beard, and slightly hurried manner. From a distance, in those few minutes I formed an expectation about his personality: Blasé and probably a bit curt; someone who really doesn’t want to be here. But when I came face-to-face with him and placed my order, I could feel his liveliness, warmth, and friendliness. My expectations needed revising. It’s the same with cities. From a distance, from an airplane or a photograph, we notice macro features and sweeping patterns that might form our first impressions. Noticing the layout of streets or the pattern of buildings from the air we might say something like “Oh, what an impressive skyline!” or “This place is a dump!” For instance, New York, London, Paris have distinct skylines. Approaching these cities from the air is thrilling as we spot the Empire State Building dominating Midtown Manhattan, Big Ben and Parliament along the Thames, or the Eiffel Tower standing counterpoint to la Defense. Tokyo’s on the other hand is a different story, but that difference is informative. Tokyo’s skyline is, at least to me, terribly underwhelming. Heavily bombed and burned during World War II and subject to devastating earthquakes throughout its history, Tokyo has few tall buildings compared to other major cities. Even as you drive in closer along the highway from Narita Airport the architecture for the most part remains boxy and drab. When you actually enter the central city, with the Sumida River winding […]

“In fine, I see from our example that human society holds and is knit together at any cost whatever. Whatever position you set men in, they pile up and arrange themselves by moving and crowding together just as ill-matched objects, put in a bag without order, find of themselves a way to unite and fall into place together, often better than they could have been arranged by art.” Michel de Montaigne

[In this space I’ll be posting quotes, ideas, and excerpts relating to a book I’m writing (thus far untitled), which I might describe as “What I have learned from the economic and social theory of Jane Jacobs.” My hope is to get thoughtful, informed feedback that will be useful in shaping the book.] Architects and planners refer to something called the “built environment” by which they usually mean things such as city streets and pathways and the grids made up by them, buildings of various kinds, plazas, the infrastructure of water and energy inflow and outflow, parks and recreation areas, unbuilt open spaces. Although parts of each of these urban elements were consciously constructed, usually by a team of individuals, the way that they fit together, except in the case of mega- and giga-projects, are not the result of a deliberate plan. Buildings in a particular location, for example, – offices, schools, residences, retail, malls, entertainment, places of worship, research facilities – are of different vintages, constructed by different people for different purposes at different times with different techniques, historical contexts, and sensibilities. But the way they all more-or-less complement one another, their “fit,” is an emergent, unplanned phenomenon. I will refer to these elements collectively as the “built framework,” where the word “built” should not in all cases imply deliberate design. What goes on within the built framework can also be planned or unplanned There are, of course, the activities for which a particular element is intended (most recently, that is, because spaces can have multiple uses over time). A gas station, what we might call a “specialized space,” is primarily for pumping gas, not for seeing a football game, which you do at a stadium. But there are other activities that take place in or are facilitated by a given element, […]

The starting point for Jacobs’s analysis and the focus of much of her thought is the city, its nature and significance. There are plenty of books out there that in some way celebrate cities. Many describe cities as engines of economic development, wellsprings of art and culture, and incubators of ideas religious, social, and scientific. But few go very far in explaining why and how all that usually happens in a city. Fewer still view the urban processes as expressions of “emergence,” or what some social theorists describe using the related term “spontaneous order.” That is the perspective of this book and its main contribution: To look closely at what makes a city a spontaneous order and an engine of innovation, and to trace the analytical and policy consequences of viewing it this way. Jane Jacobs is one of those exceptions, indeed an outstanding one. In fact, she is probably the first to carefully examine, not only the nature and significance of cities, but to distill realistic principles that govern urban systems and to analyze the mechanisms of economic change that follow from those principles. Her analysis of the relation between the design of public space and social interaction offer insights that complement, and often exceed, those of Max Weber, Henri Pirenne, Georg Simmel (pdf), Kevin Lynch, and others. Her work also has deep connections with modern social theorists such as F.A. Hayek, Elinor Ostrom, Mark Granovetter, and Geoffrey West. But she was not the first to develop conceptual tools congenial to understanding urban processes as emergent, spontaneous orders. In fact they have largely been available for decades in the field of economics, although few professional economists, including urban economists, have fully appreciated the urban origins of many of their standard concepts and tools of analysis. Indeed, there is a […]