Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

A new paper proposes that increasing diversity explains 90% of the recent decline in birthrates. Lyman Stone says it's nonsense.

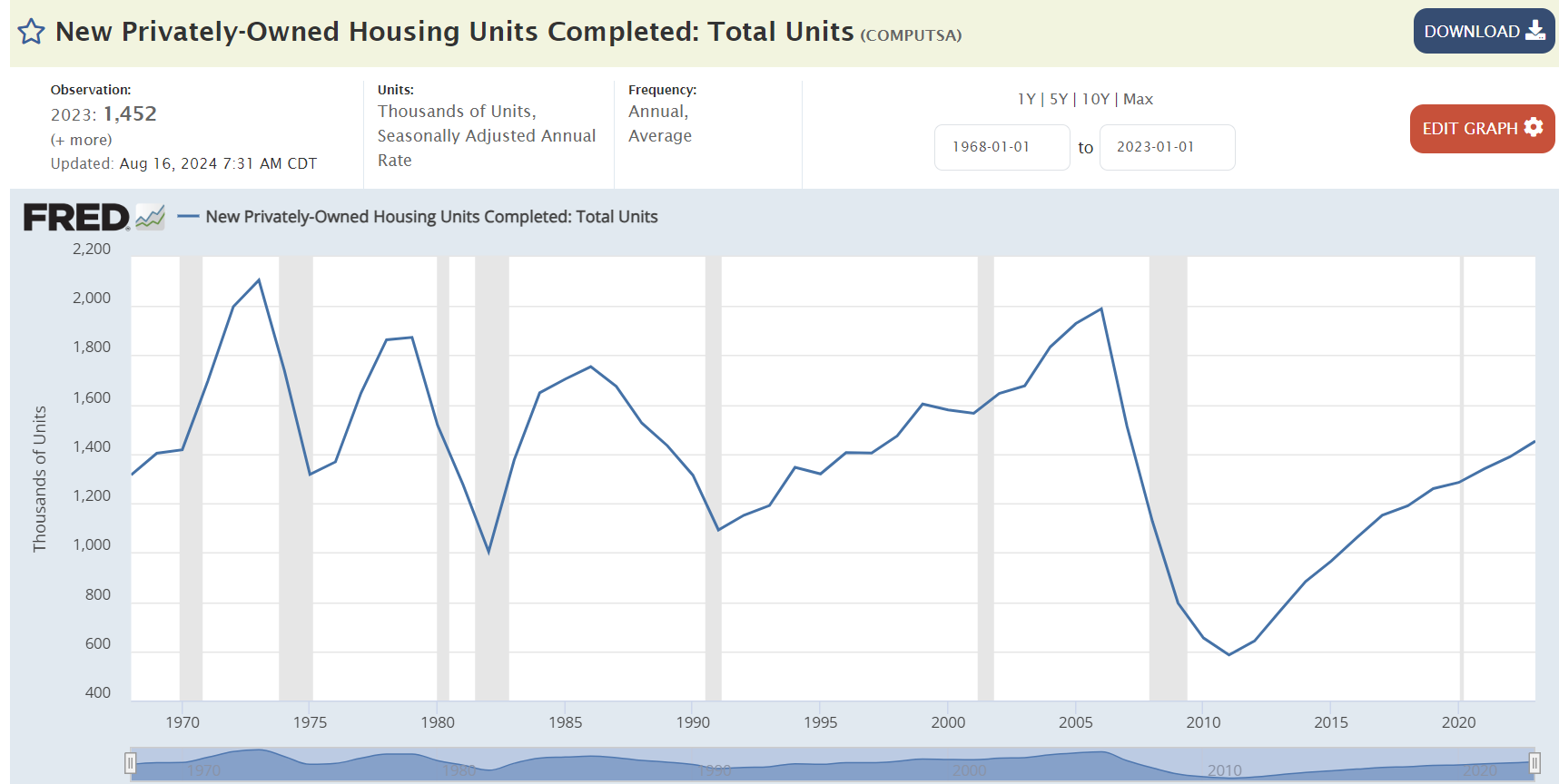

Kamala Harris has pledged to build 3 million new housing units. Setting aside the methods, what does that mean? And, would it "end America's housing shortage"?

Everyone agrees that delays and uncertainty are costly for housing development. But it’s very hard to put a number on it. The obvious costs (lawyer hours, interest over many months) are surely an underestimate. Professors Stuart Gabriel and Edward Kung have a useful answer, at least for Los Angeles: As a lower bound, simply by pulling forward in time the completion of already started projects, we estimate that reductions of 25% in approval time duration and uncertainty would increase the rate of housing production by 11.9%. If we also account for the role of approval times in incentivizing new development, we estimate that the 25% reduction in approval time would increase the rate of housing production by a full 33.0%. Delay and uncertainty go together for two reasons. One is that many delays are caused by uncertain processes, like public hearings and discretionary negotiations. The other is that market conditions change, so a developer chasing a hot market in Los Angeles is probably too late – by the time she’s leasing up, the market will have changed.

"These two homes straddle a 2010 zoning boundary change. The result: The house in duplex zoning converted into two homes, and the other converted into a McMansion that cost 80% more." - Arthur Gailes

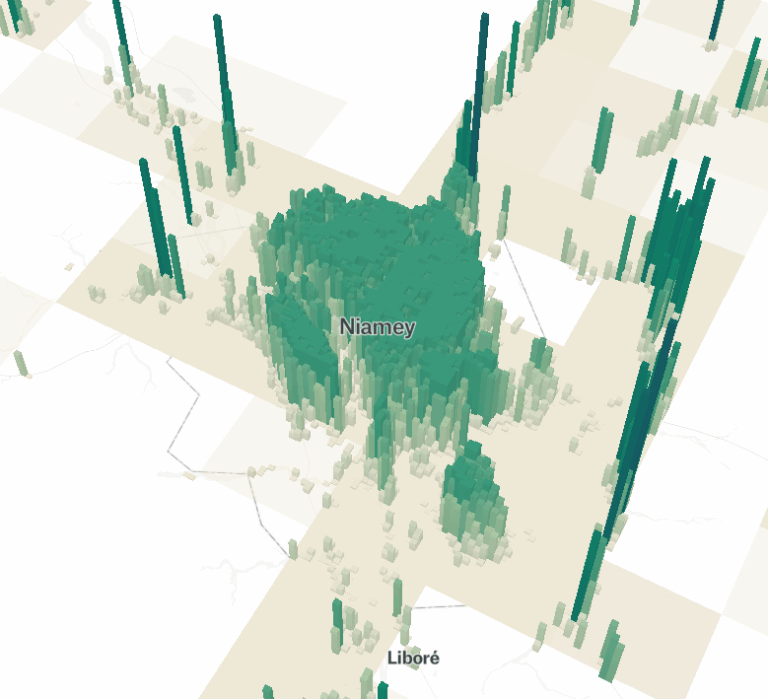

Three cool sites for data and visualizations

Kevin Erdmann offers a helpful corrective to the “YIMBY triumphalism” of claiming that large relative rent declines in Austin and Minneapolis are results of YIMBY policies. He’s mostly correct, especially about the rhetoric: arguing about housing supply from short term fluctuations is like arguing about climate change based on the week’s weather. Keep your powder dry, promise slow change and long-term stability, and recognize that demand shocks are responsible for most fluctuations. But Erdmann makes a stronger claim: Supply has never and will never cause a collapse of prices and rents. It causes stability. Is that true? In a case like Austin or Phoenix, sure: prices are not too far above the cost of construction, and abundant supply cannot (durably) push the price of new housing below the cost of construction. But YIMBY has more to offer to San Francisco, Auckland, or London. In those cases, prices are far above construction cost. That means that even when demand is relatively soft, there’s money to made in construction. As Erdmann allows: After a decade of more active construction in Auckland, rents appear to be 10% to 15% below the pre-reform trend. That’s a big win. After a decade. That’s what success looks like. That’s the promise – 5 to 15% relative rent declines, decade after decade. But there are several good reasons to believe this won’t happen in an even, steady pattern, at least not all the time. Hopefully by 2040 we’ll have data from several cases and be able to describe the dynamics of market restoration with much more confidence.

The benefit-cost ratio of housing supply subsidies looks terrible. And the state of research is even worse.

The traditional model of cities proves useful yet again - even when researchers neglect their discipline's roots.

NYU professor Arpit Gupta has channeled the annoyance of economists into a blog post directly calling out the Strong Towns "growth Ponzi scheme" line of argument.

A 2017 increase in allowed floor area ratio in Mumbai had a tremendous impact on affordability by accidentally improving the economics of smaller apartments.