Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

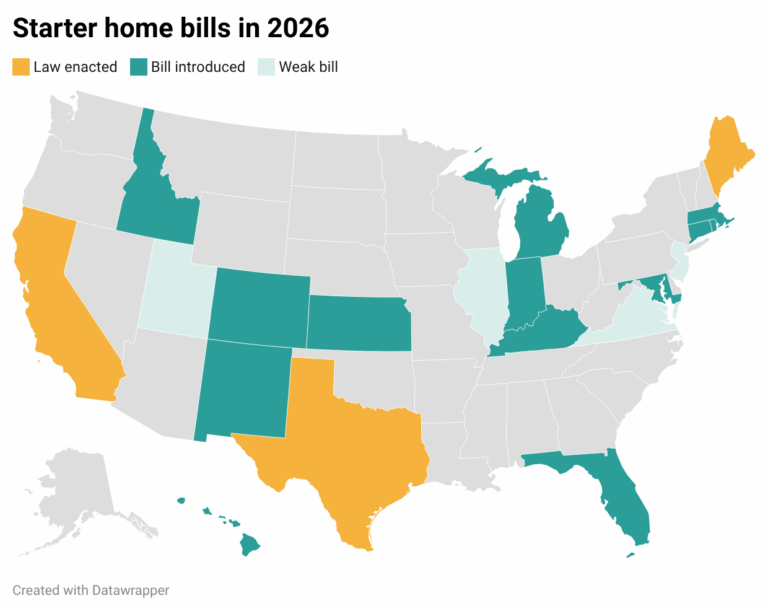

Updated 2/19 to add Michigan, 2/17 to add Kentucky, 2/16 to add Idaho, 2/11 to add Connecticut; 2/5 to add Colorado; and 1/30 to add Hawaii, Kansas, New Mexico, and Rhode Island. After decades of background study and advocacy –…

In the WSJ, Jeff Yass & Steve Moore play the world’s smallest violin for the poor homeowners who are sitting on more than half a million dollars of nominal capital gains and therefore cannot sell. If only that tiny number…

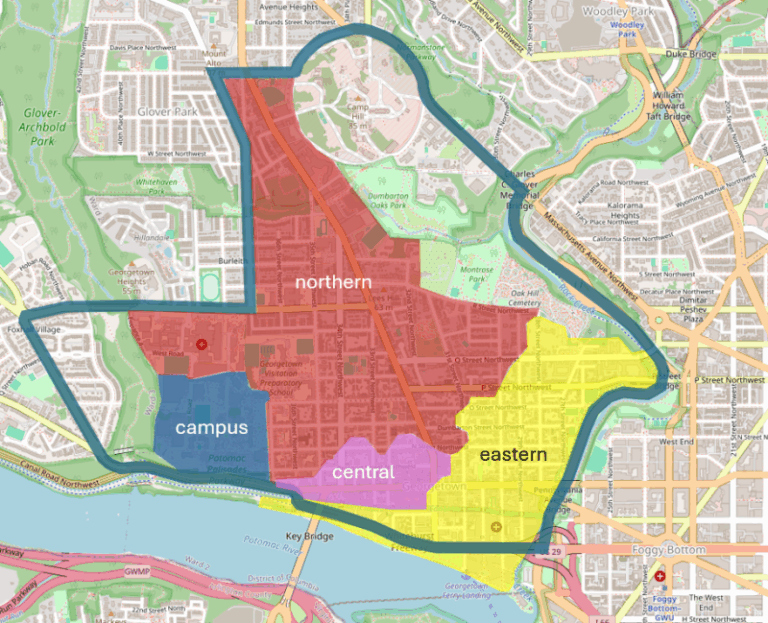

In Greater Greater Washington, my dad and I have a new editorial explaining how a ring-and-access traffic circulation plan inspired by the Netherlands can keep necessary traffic moving while delivering neighborhood streets and iconic shopping streets from traffic. Read the…

A Vietnamese business paper provides a fascinating window on land prices – official versus market – in an economy that has partially transitioned from socialism to markets: Hanoi has been collecting public feedback on its first-ever land price list, set…

Are rising prices in Kalamazoo a symptom of “climate refugees” moving to the cool, Rust Belt uplands? That’s a hypothesis put forward by a friend who works in the climate-insurance-housing cost nexus. It’s a provocative hypothesis. How else can one…

I frequently reference my post summarizing the interesting research at last year’s Urban Economics Association conference. This year was as insight rich as ever. And the Montreal setting was truly special – it’s a city that’s as European as any…

I walked down the 400 block of K St with an international guest last night. It was hard to describe the transformation of the street. Google Streetview, however, has been there almost since the beginning. 2007 2011 2014 2017 2018…

In my day job, I suggested the name “Urbanity” for the research project that Emily Hamilton and I co-lead. I wasn’t sure about it myself, but it stuck. The noun urbanity, of course, refers both to the quality of being…

On April 17, 1980, the Washington Post ran a curious paragraph, reporting a five-year-old quote for the first time – one withheld originally out of deference to the source: [Douglas Schneider’s] views of urban transportation were spelled out clearly in…

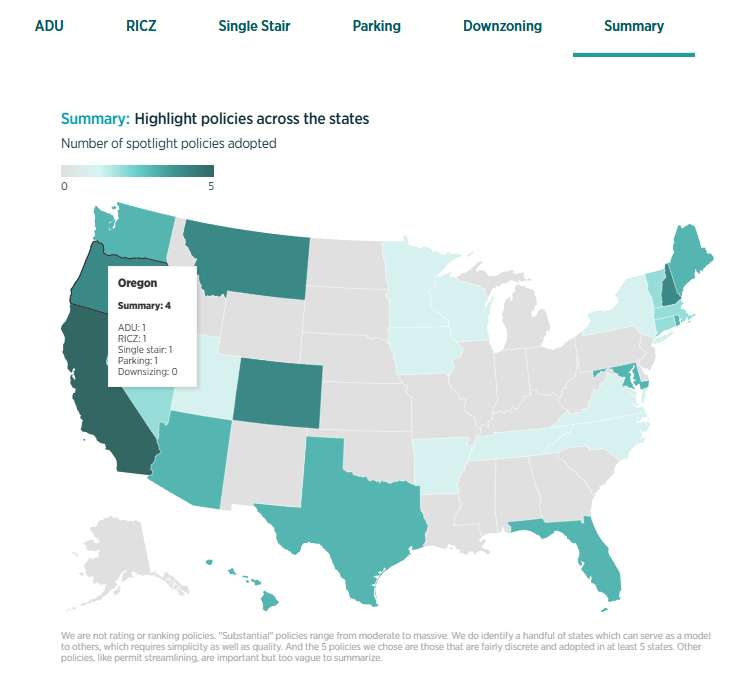

With a hugely productive legislative season in 2025, pro-homes legislators are rapidly taking good ideas around the country. To keep track of it all, my team created a new set of interactive maps. You can see snapshots here: Our goal…