Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Cities are fantastically dynamic places, and this is strikingly true of their successful parts, which offer a fertile ground for the plans of thousands of people. – Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities For most of the field’s history, prominent urban planning theorists have taken for granted that cities require extensive central planning. With the question framed as “To plan or not to plan?” students and practitioners answer with an emphatic “Yes,” subsequently setting out to impose their particular ideal order on what they perceived to be, as Lewis Mumford put it, “solidified chaos.” Whether through the controlled centralization of Le Corbusier or the controlled decentralization of Ebenezer Howard and Frank Lloyd Wright, cities were to be just that: controlled. When in 1961 Jane Jacobs set out to attack the orthodox tradition of urban planning, it was this dogma that landed squarely in her crosshairs. With her characteristically deceptive simplicity, she invites us to ask, “Who plans?” While many take Jacobs’ essential contribution to be her insights into urban design, her subversion begins at the theoretical level in the introduction to The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Despite their diverse aesthetic preferences, Corbusier and Howard share much in common. Both assume that planning entails the enshrining of a single plan and the suppression of all other individual plans. Both insist on imposing a “pretended order” on the “real order,” treating the city as a simple machine rather than a manifestation of organized complexity. Like Adam Smith’s “man of system,” each thinker was “so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he [could not] suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it.” Jane Jacobs’ critique of this orthodox tradition unfolds in three steps, closely following F.A. Hayek’s argument in […]

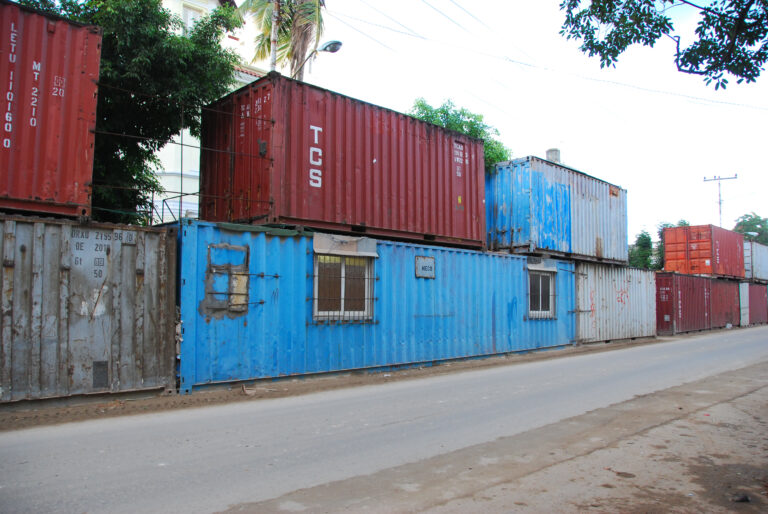

Washington, D.C. has a monopoly on many things. Bad policy, unfortunately, isn’t among them. Last month, a development corporation in Lexington, Kentucky installed a shipping container house in an economically distressed area of town to improve housing affordability. The corporation is a private non-profit, though a line near the end of this article indicates that the project received public support: “The project is funded through an assortment of grants from the city’s affordable housing fund [and two philanthropic organizations].” Shipping container projects designed to improve housing affordability aren’t limited to my Old Kentucky Home: a quick Google search reveals that the idea of using shipping containers to put a dent in housing costs is popular among policymakers and philanthropists all over the world. The sad reality is that shipping container homes likely have little—if any—role to play in handling the nationwide housing affordability problem. Aside from being inefficient for housing generally, there’s decent evidence that shipping containers appeal far more to reasonably well-off, single urbanites than to working families in need of affordable housing. More broadly, the belief that these projects could address the growing affordability crisis hints at a profound misunderstanding of the nature of the problem and distracts policymakers from viable solutions. Before digging into the meatier problems, it’s worth looking first at the problems with the structures themselves. I’ll yield to an architect: Housing is usually not a technology problem. All parts of the world have vernacular housing, and it usually works quite well for the local climate. There are certainly places with material shortages, or situations where factory built housing might be appropriate—especially when an area is recovering from a disaster. In this case prefab buildings would make sense—but doing them in containers does not. The source goes on to detail the enormous costs associated with zoning approval, insulation, and utilities. Then there’s the somewhat obvious fact that they’re small. As in, 144 square […]

Cities, for most of human history, were dumb. At least, that’s what the “smart cities” movement might lead you to believe. Over the past few years, a chorus of acquisitive multinational tech corporations, trend-savvy politicians, and optimistic developers—an odd mixture of former SimCity players, in all likelihood—has come to sing of technology’s potential to solve urban problems. Through implementation of technologies like augmented physical infrastructure, central command centers, and information exchange, proponents of smart cities argue that information technology offers new solutions to old problems like trash collection, public health, and traffic congestion. While the movement’s ideological variations are many and varied, a focus on top-down smart city solutions has ultimately distracted urban observers from the bottom-up smart city revolution that’s already underway. In his 2014 book Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia, scholar Anthony M. Townsend paints a troubling picture of the former in Rio de Janeiro’s modestly titled Center for Intelligent Operations. Developed by IBM, the center acts as a hub for hundreds of surveillance cameras and sensors. At best, the center achieves little more than, in Townsend’s words, “looking smart.” At worst, the center seems to be a regression back to twentieth century centralization. Townsend’s explorations of Songdo, South Korea, a city purported to be both centrally-planned and smart, hardly quells these concerns. The discussion leaves the reader with a healthy skepticism of top-down smart city solutions. Other criticisms have made the top-down smart city feel less like something out of 1984 and more like something out of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. In a couple of recent posts, Emily points out the roadblocks presented by poor incentives and a lack of market signals, both for politicians and high-ranking public servants. For similar reasons, both parties lack the incentives to implement […]