Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Believe it or not, the YIMBY movement won a lot in 2018. It kicked off with January’s high of California State Senator Scott Wiener’s introduction of SB 827, which would have permitted multifamily development near transit across the state, but fell to a low after its eventual defeat in committee, invariably followed by a flurry of think pieces about how the pro-development movement had “failed.” At the time, I made the case for optimism over on Citylab, but that didn’t stop the summer lull from becoming a period of soul searching within the movement. And then, a strange thing happened: YIMBYs started winning, and winning big. In August, presidential-hopeful Senator Cory Booker released a plan to preempt exclusionary zoning using Community Development Block Grant funds, quickly followed by a similar plan from Senator Elizabeth Warren in September. Also in August, Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson unexpectedly outed himself as a YIMBY. Then, in December, things really got crazy: two major North American cities, Minneapolis and Edmonton, completely eliminated single-family zoning. States like Oregon soon started talking about doing the same. In the same month, California kicked into overdrive: San Francisco—ground zero for the YIMBY movement—scrapped minimum parking requirements altogether. State Senator Wiener introduced a newer, sharper version of SB 827. And rolling into 2019, elected officials at every level of California government—from the state’s new Democratic governor to San Diego’s Republican mayor—are singing from the YIMBY hymn sheet. All in all, it wasn’t a bad year for a movement that’s only five years old. But what really made 2018 such an unexpected success for YIMBYs? Focus on Citywide Reform Over Individual Rezonings Showing up and saying “Yes!” to individual projects that are requesting a rezoning, variance, or special permit is bread-and-butter YIMBY activism. And while YIMBYs should still […]

With the Democrats scrambling to come up with a legislative agenda after their November takeover of the House of Representatives, an old idea is making a comeback: a “Green New Deal.” Once the flagship issue of the Green Party, an environmental stimulus package is now a cause de celebre among the Democratic Party’s progressive wing. While it looks like the party leadership isn’t too receptive to the idea, newly-elected Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has spearheaded legislation designed to create a “Select Committee for a Green New Deal.” The mandate of the proposed committee is ambitious, possibly to a fault. At times utopian in flavor, the committee would pursue everything from reducing greenhouse gas emissions to labor law enforcement and universal health care. A recent plan from the progressive think tank Data for Progress is more disciplined, remaining focused on environmental issues, with clearer numerical targets for transitioning to renewable energy and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Yet in all the talk about a Green New Deal, there’s a conspicuous omission that could fatally undermine efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: little to no focus is placed on the way we plan urban land use. This is especially strange considering the outsized role that the way we live and travel plays in raising or lowering greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), transportation and electricity account for more than half of the US’ greenhouse gas emissions. As David Owen points out in his book “Green Metropolis,” city dwellers drive less, consume less electricity, and throw out less trash than their rural and suburban peers. This means that if proponents of the Green New Deal are serious about reducing carbon emissions, they will have to help more people move to cities. One possible reason for this oversight is that urban planning […]

Alain Bertaud’s long awaited book, Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, is out today. Bertaud is a senior research scholar at the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management and former principle urban planner at the World Bank. Working through a pre-release copy over the past few weeks, I can confidently say that the book is an instant classic of the urban planning genre, and will be of significant special interest to market urbanists in particular. Rare among writers in this space, Bertaud brings an architect’s eye, an economist’s mind, and a planner’s experience to contemporary urban issues, producing a text that is theoretically enriching and practically useful. Alain and Marie-Agnes—his wife and research partner—have lived in worked in over a half-dozen cities all over the world, from Sana’a to Paris to San Salvador to Bangkok. For the reader, this means that Bertaud can speak from experience, supplementing data and theory with entertaining, real world examples and war stories. Order your copy today!

Earlier this year, researchers Paavo Monkkonen and Michael Manville at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) conducted a survey of 1,300 residents of Los Angeles County to understand the motives behind NIMBYism. As part of the study, they presented respondents with three common anti-development arguments, including the risk of traffic congestion, changes to neighborhood character, and the strain on public services that new developments may bring. But according to their findings, the single most powerful argument motivating opposition to new development was the idea that a developer would make a profit off of the project. At first blush, this finding might seem kind of obvious. People really don’t like developers. As Mark Hogan observed last year on Citylab, classic films from “It’s a Wonderful Life” to “The Goonies” depict developers as money-grubbing villains. But, when you think about it, it’s pretty weird that this is the case. In what other contexts do we actively dislike people who provide essential services, even if they happen to turn a profit? I don’t begrudge the owner of the corner grocery every time I buy a loaf of bread or a gallon of milk, and I hope you don’t either. In fact, most of us are probably happy that folks like doctors and dentists earn a lot for what they do. So why are developers, who provide shelter, any different? One possibility is that developers are often, for lack of a better term, assholes. This is surely the case with at least some developers. Our president is arguably America’s most famous developer, even if he isn’t exactly the master builder he played on television. And President Trump’s defining characteristic in his “Celebrity Apprentice” role—and evidently in real life—is that he is a bit of an asshole. But it isn’t just him. Most cities have […]

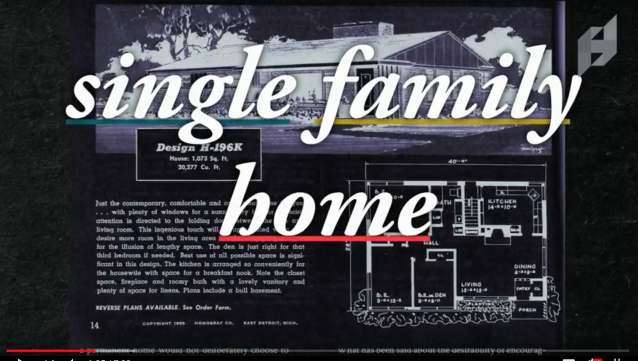

It’s an understatement to say that zoning is a dry subject. But in a new video for the Institute for Humane Studies, Josh Oldham and Professor Sanford Ikeda (a regular contributor to this blog) manage to breath new life into this subject, accessibly explaining how zoning has transformed America’s cities. From housing affordability to mobility to economic and racial segregation to the Jacobs-Moses battle, they hit all the key notes in this succinct new video. If you need a go-to explainer video for the curious new urbanists, this is the one. Enjoy!

When I first became interested in urban planning, I believed a piece of professional mythology that went like this: “For all its faults, Euclidean zoning was a well-meaning effort to expand nuisance regulation in the face of the urban industrialization. It was later practitioners who used zoning for selfish and exclusionary purposes.” While not totally without basis, I now think this view is wrong. Today I would like to show how the iconic example of a nuisance that supposedly motivated Euclidean zoning—the Equitable Life Building in New York City—was in large part controversial because it threatened the interests of existing landlords. The Equitable Life Building at 120 Broadway was completed in 1915. A vanity project of an industrialist—Thomas Coleman duPont—as so many skyscrapers were and are, the projected stood 42-stories high across an entire block without setbacks, adding a startling one and a quarter million square feet of rentable office space to Lower Manhattan. Needless to say, some New Yorkers weren’t happy. But why? The conventional wisdom holds that the Equitable Life Building caused such a stir because it literally cast a shadow over the rest of the neighborhood. Indeed, the building cast a shadow stretching nearly a fifth of a mile across Broadway. But it wasn’t just the shadows that made the Equitable Life Building so uniquely audacious—after all, it wasn’t the tallest building in the neighborhood (this honor would go to the Woolworth Building, completed four years earlier 1912) and it wasn’t the first skyscraper to take up an entire city block without setbacks (by this point, the Flatiron Building was already an icon of the city). Rather, what made the project especially upsetting, on top of standard concerns about light and air, was that it was adding so much floor space at a time when the Lower […]

On June 24 in Brooklyn, a driver in an SUV struck and killed four-year-old Luz Gonzalez, with many onlookers claiming the incident was a hit-and-run. The New York Police Department disagrees, and has refused to prosecute the driver, sparking multiple street protests. Beyond seeking justice for Gonzalez, activists demand that the city expand the use of speed cameras in school zones, which they hope could prevent further tragedy. Yet precisely at the moment that the community is most sensitive to the risk that dangerous driving poses to children, the New York state legislature shut off 140 school zone speed cameras. Given their unambiguous success in improving traffic safety in school zones, legislators should act now to renew and expand the program. While there is rare consensus among Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio on the need to preserve and even expand the traffic camera program to 290 cameras, the expansion faces opposition from some members in the Senate. Opposition to the cameras has been lead by Republican State Senator Martin J. Golden—himself a notorious school zone speeder, having received over 10 tickets since 2015 alone—and Democrat State Senator Simcha Felder, who ineffectively used the cameras as a bargaining chip to install police officers in schools. Since their implementation in 2014 as part of the broader Vision Zero initiative, school zone speed cameras have already substantially improved pedestrian safety in New York’s school zones. According to one study by the New York City Department of Transportation, the number of people killed or seriously injured in crashes in schools zones has fallen by 21 percent to 142 since the cameras came online. This is due in part to the fact that speeding drivers are getting the message: in the first 14 months following implementation of cameras, speeding violations in school […]

At first blush, the enterprise of interpreting the Jane Jacobs’ work might seem like one best left to the proud and peculiar few, or to put it less charitably, those of us with nothing better to do. Yet the forces of history militate against this apathy: Jane Jacobs has emerged as quite possibly the most important figure in North American urban planning in the second half of the twentieth century. Her work is now taught in every urban theory and urban planning program worth its weight in ESRI access codes. She is responsible for introducing hundreds of thousands of people to planning and urbanism (including this author) and continues to shape how many of us think about cities. In one of my more popular blog posts here on Market Urbanism—and in a forthcoming book chapter—I argue that we should interpret Jane Jacobs as a spontaneous order theorist in the tradition of Adam Smith, Michael Polanyi, and F.A. Hayek. Built into her work is a profound appreciation of the importance of local knowledge, decentralized planning, and the spontaneous orders that structure urban life. Needless to say, this is not the prevailing interpretation of the importance and meaning of Jacobs’ work. Two very different alternative interpretations prevail. In this post, I argue that both interpretations are mistaken. Jane Jacobs, Form-Based Coder Many have taken Jacobs’ particular critiques of conventional U.S. zoning, often referred to as “Euclidean zoning,” as motivating a new form of zoning that takes into account her observations on design. In contrast to the mandates of Euclidean zoning, which proscribes land-use segregation and low densities, Jacobs celebrated mixtures of land uses and urban densities. Jacobs spends large sections of Death and Life discussing in detail particular urban designs that she sees as essential to fostering urban life. Much of “Part One” focuses on […]

How much should we blame planning for the degree to which cities sprawl? As much time as we (justifiably) spend here on this blog explaining how conventional U.S. planning drives excessive sprawl, it’s worth periodically remembering that, at the end of the day, the actual extent of the horizontal expansion of cities is largely outside the control of urban planning. Consider Houston. Whenever I say anything nice about Houston’s relatively liberal approach to land-use regulation, someone invariably comments some variation of the following: “Yes, that’s all well and good in theory. But in practice, heavily regulated cities like Boston are far more urban and walkable, so maybe relaxed land-use regulations aren’t so great.” Indeed, most of Houston is classic sprawl. But this begs the question: to what extent can urban planning policy be blamed for sprawl? The urban economist Jan Brueckner, drawing on an extensive literature, distinguishes between the “fundamental forces” that naturally drive urban growth outward and the market failures that push this growth beyond what might occur in an appropriately regulated market. (For the purposes of this post, I’ll be using “sprawl” and “horizontal urban expansion” interchangeably. In the same paper, Brueckner thoughtfully distinguishes the two.) The latter, urban planners can address. The former, not so much. Let’s look first at the “fundamental” variables that planners have little to no control over. Brueckner identifies three: population growth, rising income, and falling commuting costs. The first variable is obvious: as cities grow, demand for all housing goes up, and some of that housing goes out on the periphery regardless of planning policy. Metropolises like Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta are currently experiencing 2% population growth every year, meaning they are on track to double in population in the next 35 years. You would expect a lot of horizontal expansion, all else […]

In most of my discussions of Houston here on the blog, I have always been quick to hedge that the city still subsidizes a system of quasi-private deed restrictions that control land use and that this is a bad thing. After reading Bernard Siegan’s sleeper market urbanist classic, “Land Use Without Zoning,” I am less sure of this position. Toward this end, I’d like to argue a somewhat contrarian case: subsidizing private deed restrictions, as is the case in Houston, is a good idea insomuch as it defrays resident demand for more restrictive citywide land-use controls. For those of you who haven’t read my last four or five wonky blog posts on land-use regulations in Houston (what else could you possibly be doing?), here is a quick refresher. Houston doesn’t have conventional Euclidean zoning. Residents voted it down three times. However, Houston does have standard subdivision and setback controls, which serve to reduce densities. The city also enforces high minimum parking requirements outside of downtown. On top of these standard land-use regulations, the city heavily relies on private deed restrictions. Also known as restrictive covenants, these are essentially legal agreements among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property, often set up by a developer and signed onto as a condition for buying a home in a particular neighborhood. In most cities, deed restrictions cover superfluous lifestyle preferences not already covered by zoning, including lawn maintenance and permitted architectural styles. In Houston, however, these perform most of the functions normally covered by zoning, regulating issues such as permissible land uses, minimum lot sizes, and densities. Houston’s deed restrictions are also different in that they are heavily subsidized by the city. In most cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by parties to a deed, typically organized as a […]