Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

One long-forgotten housing option is residential hotels; a century ago, most renters lived in hotels and shared space with short-term tenants. I just read a book, Living Downtown, about the rise and fall of residential hotels. Rather than discuss them in detail I refer you to my amazon.com review. But here are two general thoughts: one reason Airbnb has been controversial is because it mixes long-term and short-term tenants. But in the first half of the 20th century this was a common mixture. Until the 1920s, residential hotels were so unregulated that they included a wide range of places, from luxury hotels to vile flophouses where there was not even a mattress to sleep on. But this mixture allowed even tramps to avoid sleeping on streets as they do now.

Ever since zoning was invented in the 1920s, homeowners have argued that limits on density and on multifamily housing are necessary to protect property values. But today, urban NIMBYs seek to prevent new housing on the ground that new housing will lead to gentrification, which will in turn lead to increased property values, which in turn will lead to rising rents and displacement. Similarly, I often read that cities and suburbs shouldn’t have any new housing because they might become “too dense” or “overcrowded.” (Never mind that when there’s not enough housing to go around, excluded residents respond not by leaving the city, but by sleeping on the streets, thus making the city feel even more crowded). But at the same time, I also read that building new housing is futile, because it will all be bought up by foreign oligarchs, who (because they aren’t quite greedy enough to rent out their property) cause the housing to be lifeless and unoccupied. It is not quite clear to me how the city can be overcrowded and undercrowded at the same time, but evidently this view seems to be common.

In a recent blog post, Julia Galef has generated a fairly comprehensive list of pro-housing arguments and counterarguments to those arguments. She gives the most detailed consideration to the “infinite demand” argument- in her words, “So even if SF adds a lot of additional housing, prices will still rise almost as quickly as they would have anyway, as long as demand to live here continues to soar. This view is mainly based on examples of other desirable cities, like New York or Singapore, which have built new housing at a faster rate than SF but nevertheless saw steep increases in price.” To which I respond: New York? Really? New York is only pro-housing when compared to San Francisco- which is a bit like saying Iran is a libertarian paradise compared to the Islamic State. In fact, New York has built housing at a glacial pace. Between 1960 and 1976, the number of new housing units completed per year ranged from just over 14,000 to over 60,000, and exceeded 20,000 in all but four years. In the almost forty years since 1976, the number of new units exceeded 20,000 in only four years (2006-10) and was above 14,000 for only ten years (1989, 2002, 2004-10, 2015). Meanwhile, demand for housing has increased: between 2006 and 2014 alone, the citywide renter population grew by 600,000. A better example of a “desirable city” would be a city where both the population and the housing supply is growing at a rapid rate- Raleigh, for example, or Las Vegas. These cities are much cheaper than New York or San Francisco.* Another example of a cheap, permissive city is Tokyo. But the post suggests Tokyo may not have grown as fast as American cities. In fact, Tokyo’s regional population grew by 17 percent since 1990- from 32.5 million […]

I recently saw a Facebook post asserting that San Francisco has 30,000 vacant units, so therefore no market-rate housing should be built. So I looked up Census data on these allegedly empty units. It is true, according to the Census Factfinder website, that there are 30,000 or so unoccupied housing units in San Francisco. Does this mean that they are completely idle? In fact, no. More than half of these units were (as of the 2010 Census) currently for sale or for rent. 18 percent for for seasonal use (presumably, second homes). Only 5 percent are rented or sold but unoccupied. The rest are “other vacant”. whatever that means. Bottom line: half the vacancies were in the process of being sold or rented. A little under a fifth were second homes. About a third we don’t know much about.

The most interesting comment to my last post focused on one narrow issue: to what extent are vacant housing units second homes (and thus presumably less likely to be rented out) as opposed to units for rent/sale or held for other unknown reasons? Why does this matter? Because one might argue that even if overall vacancy rates are low, a high “second home rate” might be evidence that the city’s housing prices are rising because of nonresident investors. Unless I am missing something, 2015 American Community Survey data does not contain data at this level of detail. However, 2000 and 2010 Census data contains data on types of vacancies. Below are percentages of vacant units held (in the Census Bureau’s words) “for seasonal, recreational or occupational use.” 2000 2010 Expensive markets Manhattan 32.7 33.9 (3.3 pct of all housing units) San Francisco 22.4 17.9 Boston 12.6 15.2 Los Angeles 7.8 7.9 San Diego 26.8 23.5 Not-so-expensive markets Dallas 4.6 3.7 Houston 6.5 4.5 Philadelphia 2.5 3.2 Chicago 5.0 7.0 On the one hand, expensive markets tend to have more second homes (evidence of a wave of outsider capital). But if such outsider capital was a major cause of rising housing prices, one would expect the “second home percentage” to grow over the 2000s. Instead, this number has been pretty stable. Moreover, this group of vacancies is a pretty small percentage of the overall housing market- a bit over percent in Manhattan, and a little over 1 percent in New York City as a whole (since second homes are not so common in the other boroughs).

One common argument against new urban housing runs as follows: “If we build new housing, it will all be bought up by rich investors who will sit on it. So new supply doesn’t restrain housing costs.” This argument (at least as I have phrased it) strikes me as absurd. Here’s why: for the argument to justify restraining supply, the argument presupposes that if you build 100 new condos/houses/apartments, every single one of them will be bought by an investor, and every single investor will irrationally choose to sit on the unit rather than renting it out. I can’t prove this is wrong, but it seems really hard to believe.* Even leaving aside the logical weirdness of the argument, it seems to have a questionable factual basis. If there was really a wave of nonresident investors in expensive cities, we might find (1) that the most expensive markets had the highest housing vacancy rates and (2) that these vacancy rates have been rising as housing costs rose. But Census data suggests otherwise. Here’s some data: (all for central cities, not metros) Expensive 2010 2015 Manhattan 12.7% 13% San Francisco 9.8 7.9 Los Angeles 6.7 6.5 San Diego 7.8 7.1 Boston 9.1 8.0 Not so Expensive 2010 2015 Dallas 12.8% 10.6% Houston 14.0 12.1 Philadelphia 14.1 13.3 Chicago 13.8 13.2 By and large, the expensive cities have lower vacancy rates- exactly what you would expect in a free market. The only exception is Manhattan. But it seems to me that if pied-a-terres led to higher rents, Manhattan’s empty-house rate would have climbed as rents did- which does not seem to have been the case. The only way to save the “empty house” theory is to suggest that expensive cities’ empty houses are different from everyone else’s – that is, they are especially […]

A blog post in Pacific Standard seeks to defend rent control- an idea that, as the author admits, is generally detested by economists. The author writes that “rent regulations give tenants a greater stake in their community and incentivize them to put time, energy, and even money into their homes.” But that’s not necessarily a good thing- in a heavily regulated market, a “stake in the community” means that tenants, like homeowners, have an incentive to engage in NIMBYism. So in a prosperous area rent control hits housing supply with a double whammy- more recruits for the NIMBY army AND less incentive for landlords to invest in housing. He also endorses the “Unlimited Demand” theory, acknowledging the argument that building more market rate housing creates more affordable housing eventually, but responds: “not in tight markets like Silicon Valley and New York City. ” This claim is of course a self-fulfilling prophecy: people use it to justify opposing new housing, which in turn ensures that supply can never meet demand. (I critique the argument in more detail here). However, the article does contain one non-silly argument: that rent-controlled cities do occasionally experience building booms (most notably New York in the 1950s). Rent control is a factor relating to housing supply, but not the only one. So here’s my modest proposal for pro-regulation politicians: a city can adopt rent control to protect existing tenants, as long as they deregulate in other ways in order to promote new construction. So for example, a state law could provide that municipalities could adopt rent control under one condition: no more exclusion of new housing. So if San Mateo County wants to adopt rent control, they can do it as long as all new housing is exempt from all of the city’s use and density restrictions. The […]

Last week, I posted about an attack on YIMBYs (activists who favor less zoning and more housing) that used the term “alt-right”; the authors of that blog post recently doubled down with a slightly more moderate op-ed that still tarred YIMBYs as “aligned with conservative right-wing libertarianism.” In fact, the Obama Administration is on the same side as YIMBYs; I recently published an article about their 2016 policy paper on urban housing. Read all about it here.

The far-left “TruthOut” web page recently published an attack on YIMBYs,* describing them as an “Alt-Right” group (despite the fact that the Obama Administration is pro-YIMBY). I was surprised how little substance there was to the article; most of it was various ad-hominem attacks on YIMBY activists for cavorting with rich people. I only found two statements that even faintly resembled rational arguments. First, the article suggests that only current residents’ interests are worth considering in zoning policy, because “the people who haven’t yet moved in” most often means the tech industrialists, lured by high salaries, stock options and in-office employee benefits like massage therapists and handcrafted kombucha.” This statement is no different than President Trump’s suggestion that Mexican immigrants “[are] bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” – that is, it is an unverifiable (if not bigoted) generalization about large numbers of people. Furthermore, it doesn’t make sense. The “tech industrialists” have the money to outbid everyone else, so they aren’t harmed by restrictive zoning. Second, the article states that academic papers aren’t as relevant as the actual experiences of San Franciscans displaced by high housing costs. In response to the argument that less regulation means cheaper housing, it states “tell that to people like Iris Canada, the 100-year-old Black woman who had used local regulations to stay in her home of six decades, only to be evicted in February.” So in other words, somebody was evicted in San Francisco, therefore San Francisco’s restrictive zoning prevents eviction. I don’t see how the latter follows from the former. The whole point of the YIMBY/market urbanist argument is that if there was more housing, there would be lower housing costs, hence fewer evictions. *For those of you who are unfamiliar with the term, YIMBY means “Yes In My Back Yard”, a […]

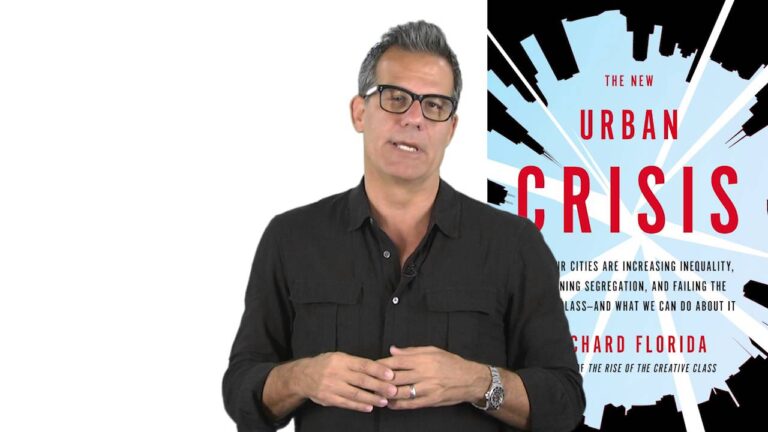

I just finished reading Richard Florida’s new book, The New Urban Crisis. Florida writes that part of this “crisis” is the exploding cost of housing in some prosperous cities. Does that make him a market urbanist? Yes, and no. On the one hand, Florida criticizes existing zoning laws and the NIMBYs who support them. He suggests that these policies not only raise housing prices, but by doing so harm the economy as a whole. For example, he writes that if “everyone who wanted to work in San Francisco could afford to live there, the city would see a 500 percent increase in jobs… On a national basis, [similar results] would add up to an annual wage increase of $8775 for the average worker, adding 13.5 percent to America’s GNP – a total gain of nearly $2 trillion” (p 27). On the other hand, Florida is not ready to endorse the idea that “we can make our cities more affordable… simply by getting rid of existing land use restrictions” because “the high cost of land in superstar neighborhoods makes it very hard if not impossible, for the private market to create affordable housing in their vicinity. Combine the high costs of land with the high costs of high-rise construction and the result is more high-end luxury housing.” (p. 28). I don’t find his point persuasive, for a variety of reasons. First, as I have written elsewhere, land prices are often quite volatile. Second, the overwhelming majority of any region’s housing is not particularly new; even in high-growth Houston, only 2 percent of housing units were built after 2010. Thus, new market-rate housing is likely to affect rents by affecting the price of older housing, rather than by bringing new cheap units into the market. Florida also writes that “too much density can […]