Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Despite its poor track record, homeownership is the bad investment idea that never seems to die. Even though the financial crisis revealed the risks that homeowners take on by making highly leveraged purchases, policymakers are still developing new programs to encourage home buying. Both the Clinton and Trump campaigns are continuing the political support for homeownership that dates back to the Progressive Era. Since the New Deal, homeownership has been touted as a tool to reduce poverty and as a route to wealth-building for the middle class. Even before the subprime-lending crisis revealed the risk that low-income borrowers took on with homeownership, researchers have explained the problems with using homeownership programs as a poverty reduction tool. Joe Cortright recently pointed out that homeownership is a particularly risky bet for low-income people who may only have access to credit during housing market upswings, leaving them more likely to buy high and sell low. Even for middle- and high-income households, homeownership is a weak investment strategy. Politicians across the political spectrum tout homeownership as key to a middle-class existence, but homeownership will make many buyers poorer in the long run compared to renting. The real estate and mortgage industries have popularized the claim that “renting is throwing your money away,” but owning a home comes with a steep opportunity cost. Renters can invest the money that they would have spent on a down payment in more lucrative stocks, and they don’t take on the risk of home maintenance. The New York Times created a popular calculator designed to determine whether renting or owning makes better financial sense. The calculator’s defaults assumptions are overly optimistic in favor of homeownership as the better strategy for most households. They include a 1% rate of house price increases after accounting for inflation, but the historical average is just 0.2%. Similarly, the calculator defaults to a […]

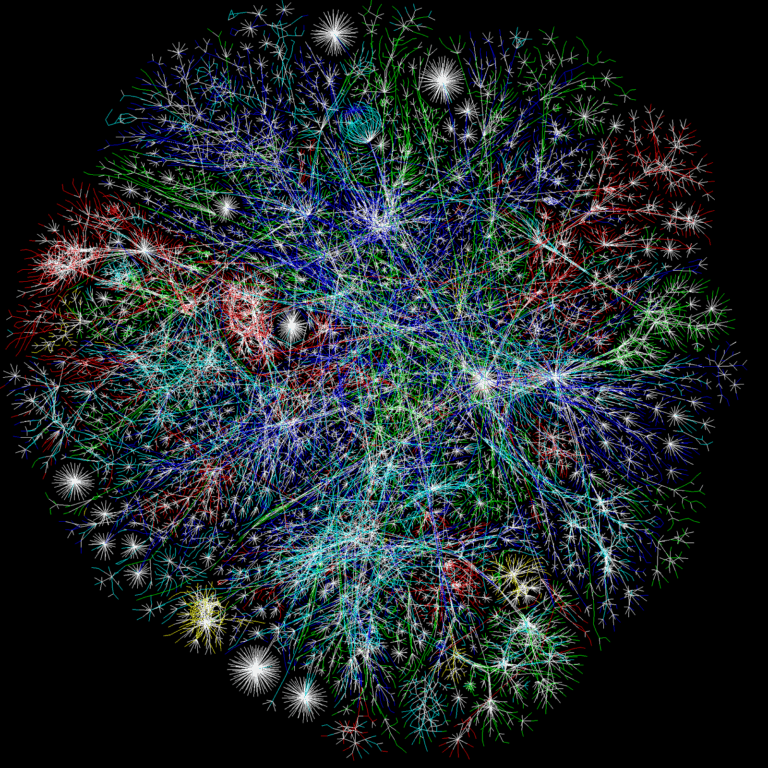

In his famous 2010 Ted Talk Matt Ridley points out that a growing human population has facilitated increasing standards of living because more people means a faster growth rate of innovation. He explains that humans’ propensity to exchange means that as a society we all benefit from each other’s ideas. No single person knows how to make a pencil from scratch, but we can all benefit from pencils (and much more complex tools) because collectively we have the knowledge to produce them. Ridley describes technological progress as a product of the collective brain — the space where our “ideas have sex.” Ideas “meet and mate” perhaps most obviously on the Internet, where the best encyclopedia in human history is crowd-sourced. This process is constant in the analog world also. The story of Microplane — a company that went from making printer parts, to woodworking tools, to kitchen gadgets and instruments for orthopedic surgeons — illustrates the innovations that come from ideas meeting and mating across entirely different industries. Cities provide the ideal location for these meetings because they bring together people from varied industries, backgrounds, and priorities. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs identifies four qualities that are necessary for diverse neighborhoods: At least two primary land uses; Small blocks; Buildings of diverse ages and types; and A high density of buildings and people. These characteristics facilitate an urban environment in which people of different professions, interests and income levels come into contact with one another as they go about their daily routines. In turn, this human contact puts people in an ideal position for innovation and entrepreneurship. Sandy Ikeda describes the entrepreneur’s environment as the “action space.” Today, an action space could be in a suburban home for an entrepreneur who creates a digital product that’s sold online. While […]

Yet another study in a long line of others provides evidence that land-use regulations restrict housing supply. A new paper identifies a correlation between land-use regulations in California cities and the growth rate for housing units. Kip Jackson finds that California zoning rules and other land-use restrictions not only reduce the growth rate of new housing stock, but a new regulation can actually be expected to reduce the existing stock of housing by 0.2% per year. This correlation is greatest when looking only at multifamily buildings, where each new restriction results in 6% fewer apartments built annually. Kip uses panel data on California land-use regulations from 1970-1995. Researchers sent surveys to municipal planning departments to create a dataset including both the regulations in effect in each city and the year they were enacted. The panel dataset allows Kip to use two-way fixed effects. That means that his results control both for factors that affect housing growth in all cities at a given time and for factors that affect growth in a specific city over time. This survey data makes it possible to study both the effects of the total quantity of rules along with the effects of specific rules. Kip finds that rules that are likely to make it more difficult to build in the future lead to an increase in building permits at the time they are implemented. For example, urban growth boundaries and rules that require a supermajority council vote to approve increased residential density spur current year housing permits. This increase is likely due to developers’ belief that building permits will become more difficult to obtain the longer the new regulation is in effect. He points out that some studies that fail to find a relationship between zoning and housing supply may find this null result because of rules that change the timing of development while reducing it over the […]

Adam Smith taught the world that mercantilism impoverished 18th-century nations by erecting barriers to trade and reducing opportunities for specialization and economic growth. Regulations that restrict urban development likewise reduce opportunities for innovation and specialization by limiting cities’ population size and density. Even as improvements in communications technology and falling transportation costs reduce the burden of distance, many industries still benefit from the geographical proximity of human beings that only dense development can provide. Removing land-use regulations will allow greater gains from trade as more people are allowed to live in important economic centers like New York City and Silicon Valley. Cities facilitate innovation by placing people with diverse backgrounds and goals in close proximity. While Israel Kirzner’s research provided a comprehensive analysis of entrepreneurs in the market process and in economic growth, economists have not given sufficient attention to the geography of entrepreneurship. The settings in which entrepreneurs work – Sandy Ikeda’s “action space” – matters, and cities provide a crucial role as the action space for much of human innovation. Silicon Valley is an urban action space where geographical proximity has made entrepreneurs more successful than they would have been without the inspiration they provided one another. The Homebrew Computer Club, a social group founded in 1975 for computer hobbyists, played a crucial role in the development of personal computers. The programmers, engineers, and inventors who attended those early meetings would go on to revolutionize computing thanks, in large part, to the information they gathered from swapping ideas, hardware, and skills from the other group members they encountered. The club began meeting in garages, parking lots, and university auditoriums, but it was only possible because these enthusiasts all worked for semiconductor companies that brought them to the same region of California. Empirical evidence bears out the importance of cities in facilitating […]

Michael Hamilton and I coauthored this post. Tyler Cowen has two new, self-recommending posts questioning whether or not market urbanist arguments are internally consistent. He argues that if land-use regulations are analogous to a tax on land, then either the benefits of deregulation would go to landowners or the costs of regulation are greatly overstated. The problem with this argument is that zoning is not a Georgist tax in which landowners are taxed in proportion to their land’s value; rather, zoning hugely decreases the value of the country’s most valuable land, while it props up the value of land that would be less desirable absent zoning. This is because zoning only acts as a tax on land to the extent that regulations are actually binding. A 250-foot height limit would create zero costs for the vast majority of the country, but would be devastating in Manhattan. Likewise, the large variation in land-use regulations across localities means that the costs of land-use regulation are imposed unevenly, even though there may be some correlation between land value and the tax imposed by zoning. Their repeal would have complicated and mixed effects. Tyler’s post focuses on desirable neighborhoods within the nation’s most highly-demanded cities because it assumes large increases in Ricardian rents from liberalization, i.e. those places where zoning is often the most binding. A broader view would also consider what would happen outside hip neighborhoods, especially exurban commuter suburbs that mostly exist because workers are excluded from areas closer to city centers. These suburbs could see land values plummet under broad liberalization. Whether these price changes are good or bad is a value judgement, but Tyler’s theoretical distributional concerns should also take potential decreases in land value into account. Empirically, cities with more liberal land-use regimes are more affordable, so the premise of zoning being analogous to a land value tax may not be accurate. Toronto, Houston, Chicago, and […]

Last week I wrote a post highlighting how important it is for major cities to have places for low-income people to live. Without the opportunity to live in vibrant, growing cities, our nation’s poor can’t take advantage of the employment and educational opportunities cities offer. My post offended some people who don’t think that reforming quality standards is a necessary part of affordable housing policy. On Twitter @AlJavieera said that my suggestion that people should have the option to live in housing lacking basic amenities is “horribly conservative.” Multiple people said that my account of tenement housing was “ahistorical.” They didn’t elaborate on what they meant, but they seemed to think I was suggesting that tenements were pleasant places to live, or that people today would live in Victorian apartments if such homes were legalized. On the contrary, I argue that in their time, tenements provided a stepping stone for poor immigrants to improve their lives, and that stepping stone housing should be legal today. Historical trends provide evidence that people born into New York’s worst housing moved onto better jobs and housing over time. The Lower East Side tenements were first home to predominantly German and Irish immigrants, and later Italian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants. The waves of ethnicities that dominated these apartments indicate that the earlier immigrants were able to move out of this lowest rung of housing. The Tenement Museum provides multiple oral histories of people who were born into their apartment building and went on to live middle-class lives. In The Power Broker, Robert Caro provides an account of one community that had moved out of the Lower East Side to better housing in the Bronx: The people of East Tremont did not have much. Refugees or the children of refugees from the little shtetles in the Pale of Settlement and from the ghettos of Eastern Europe, the Jews who at […]

The market urbanism axiom — permitting housing supply to increase is key to achieving affordable housing — has been made recently by Rick Jacobus at Shelterforce and Daniel Hertz at City Observatory. However both argue that even with an increasing supply, low-income people will need aid in order to afford what the authors feel is adequate housing. History shows us, though, that if developers are allowed to serve renters in every price range, they will. The movie Brooklyn portrays the type of housing many of our grandparents and great-grandparents lived in when they emigrated to the United States. People of very little means could afford to live in cities with the highest housing demand because they lived in boarding houses, residential hotels, and low-quality apartments, most of which are illegal today. Making housing affordable again requires not only permitting construction of more new units, but also allowing existing housing to be used in ways that are illegal under today’s codes. Young adults living in group houses with several roommates have found a way around these regulations, but low-income renters were better-served when families and single people could pay for housing that was designed to meet their needs at an affordable price. Alan During explains the confluence of interest groups that successfully eliminated cheap, low-quality housing: The rules were not accidents. Real-estate owners eager to minimize risk and maximize property values worked to keep housing for poor people away from their investments. Sometimes they worked hand-in-glove with well-meaning reformers who were intent on ensuring decent housing for all. Decent housing, in practice, meant housing that not only provided physical safety and hygiene but also approximated what middle-class families expected. This coalition of the self-interested and the well-meaning effectively boxed in and shut down rooming houses, and it erected barriers to in-home boarding, too. Over more than a century, […]

To market urbanists and many others, it’s clear that there is a positive relationship between high housing costs and land-use restrictions and that liberalizing zoning would lower housing costs relative to what they would be in a more regulated environment. Given this relationship, reducing zoning would improve efficiency in the housing market by allowing consumer demand to drive the amount of resources that are put into housing development. However, land-use reform would also affect other policy areas such as public schools, transportation infrastructure, and sewer and water provision. Predicting how a liberalizing reform in one policy area will affect the complete public policy landscape is as impossible as predicting how one private sector innovation will affect other markets. Political scientist Steven Teles coined the term “kludgeocracy” to describe the complexity of contemporary American policy. For example, zoning has become a tool to make high-performing public schools exclusive, even though land-use policy and education policy are seemingly unrelated areas governed by different agencies. Because providing zero-price quality education to every child in the country may be impossible, zoning is a kludge that allows policymakers to provide this service to their high-income and influential constituents. Teles describes this policy complexity: A “kludge” is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “an ill-assorted collection of parts assembled to fulfill a particular purpose…a clumsy but temporarily effective solution to a particular fault or problem.” The term comes out of the world of computer programming, where a kludge is an inelegant patch put in place to solve an unexpected problem and designed to be backward-compatible with the rest of an existing system. When you add up enough kludges, you get a very complicated program that has no clear organizing principle, is exceedingly difficult to understand, and is subject to crashes. Any user of Microsoft Windows will immediately grasp the concept. […]

Forest City Enterprises recently received approval from Arlington County to redevelop its Ballston Common Mall. The deal is a public-private partnership in which the county will pay for $10 million in infrastructure improvements around the mall and provide $45 million in tax increment financing for the reconstruction. The deal is not only a waste of taxpayer money, but it also perpetuates development through political favoritism as opposed to allowing competition to determine the best use of land. Opened in 1986, today Ballston Common Mall is a sad structure with a high vacancy rate. However, a public-private partnership isn’t needed to turn it into an updated, profitable development. The mall sits on incredibly valuable land. A nearby parcel less than half the size of the mall site recently sold for $7.5 million. With demand so high for land along Arlington’s Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor, county money certainly isn’t needed to facilitate retail development. The mall owner, Forest City Enterprises, is well-versed in navigating public-private partnerships. In DC the company has received over $100 million in subsidies for recent projects. Forrest City Ratner, the corporation’s New York office, was the developer of the famed Atlantic Yards (now Pacific Park) project that has become a poster project for cronyism in real estate. Like the Atlantic Yards project, the Ballston Common Mall redevelopment will involve both direct subsidies and a TIF. The TIF that will help finance the new mall is debt financing that will be paid back with property tax increases that county officials believe the new mall will bring. This will be the first TIF ever used in Arlington. The Ballston project follows a high-profile retail development in Fairfax County, where the Mosaic District was completed as that county’s first TIF. By allowing municipal policymakers to spend future tax revenues today, TIFs provide a tool for obscuring the costs of economic development […]

In political transactions, players cannot make deals using dollars, but nonetheless they engage in trades to pursue their goals. Policymakers may engage in trades both with other policymakers and with private sector actors . While these deals are not denominated in dollars, their gains from trade can still be considered “profit” that goes to the parties to the trade. In the decision to create the DC Metro’s silver line extending from West Falls Church to Dulles International Airport, many public sector and private sector parties profited from the complex dealmaking that facilitated the extension. The Silver Line was accompanied by redevelopment planning for Tysons Corner, a suburb of DC along the line’s route. These rail construction and accompanying rezoning benefitted three primary groups. The first and most obvious beneficiaries of the development of the Silver Line were the individuals and corporations that owned large parcels of land near the planned stations. The value of their holdings increased not only because of the new infrastructure, but also because the planning for the Silver Line involved significant upzoning, making more intensive and profitable use of their land legal. The combined promise of upzoning and the new metro stations ensured local policymakers that powerful landowners would support their efforts. These large landowners who benefited from upzoning include West Group, Tysons Corner Property, and West Mac Associates among other. The leadership members of these corporations were active in commenting on the proposed changes to the area’s land use and transportation plans. Because of its large investment in Tysons Corner and its corresponding importance in the development process, West Group has had special involvement in the redevelopment process. Implementing the proposed grid of streets relies heavily on West Group properties and other major developers cooperating to minimize the need to use eminent domain to achieve the infrastructure requirements to facilitate increased […]