Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

I frequently reference my post summarizing the interesting research at last year’s Urban Economics Association conference. This year was as insight rich as ever. And the Montreal setting was truly special – it’s a city that’s as European as any in North America. (But it’s still North American. One attendee from France told me he kept addressing locals in English because the setting felt so North American to him.)

Several researchers presented papers about greenbelts or urban growth boundaries, but they were scattered across sessions.

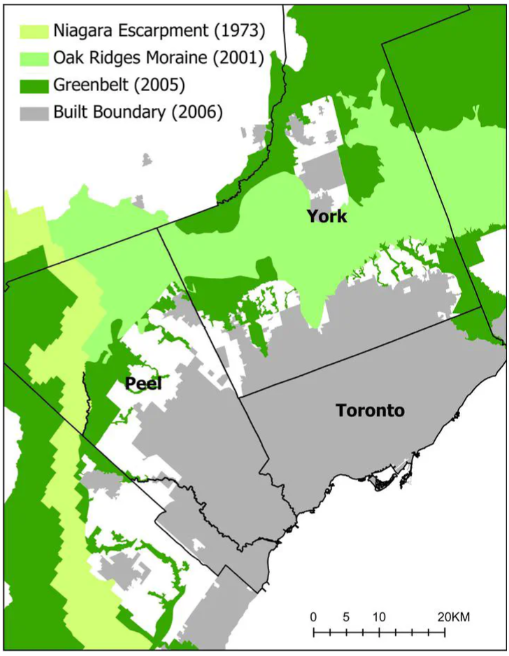

Alexander Hempel studied Toronto’s greenbelt policy, which was implemented in the 2000s. Because it was relatively loose at the time of implementation, the price effects were muted: just a 3% price increase, less than a twentieth of the total price appreciation during that period. The price effect within the greenbelt was about twice as large, which puts a low ceiling on the amenity value of living in the greenbelt. The technical challenge for Hempel is to distinguish the effects of the greenbelt from those of the accompanying urban upzonings.

Daniel Bigelow and Justin Gallagher are studying Oregon’s urban growth boundary (old slides). Their work is mainly descriptive. They find that the UGB does what it says on the tin: density is much lower outside the boundary than inside. But that, of course, only emerged over time. Oregon passed its UGB law in 1973 and mandated implementation by 1980. It was only in the mid-1990s, though, that they see evidence that UGBs were binding. This is a caution for Toronto and other recent adopters: a UGB that seems generous at implementation will eventually tighten.

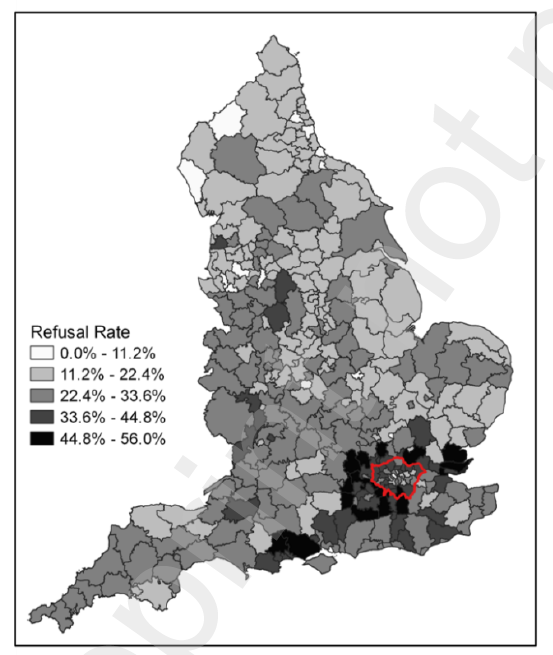

I didn’t see Lukáš Makovský and Capucine Riom‘s presentation on London’s Greenbelt. But their poster from another conference shows that a 1% increase in wages in a typical UK local authority results in 0.8% in-migration. But in the Greenbelt, wage increases have no population effect.

Job market candidate Danny Gold analyzed Seattle policies that have been a reform priority for Cascadian YIMBYs: curbing the uncertainty and delay of design review. He uses the city’s rules through 2018, which required design review for buildings of more than 8 homes. As expected, there is bunching right at 8 units and larger buildings take longer to approve than small ones. Design review with a unit-count threshold caused developers to build fewer, slightly larger apartments.

But some 9-17 unit buildings are built, and those have relatively quick approvals. He interprets this as evidence of self-selection: builders go ahead with projects just above the threshold only if they expect easy approval.

Using the universe of building permits, he estimates that design review adds 4 or 5 months to the approval process (median: 14 months). Going through design review adds $14,000 to the cost of the median building, but with a large right tail.

Thanks to state-level reforms limiting design review, Seattle suspended design review a week before the conference.

Gabriel Ahlfeldt presented a summary of the Economics of Architecture, work undertaken with E. Pietrostefani and Ailin Zhang.

Seattle’s policy – restricting supply and giving a density bonus for design review that doesn’t even achieve visibly distinct results – is even worse than the worst idea Ahlfeldt considered.

Christian Hilber presented work with Michael Ball, Paul Cheshire, and Xiaolun Yu. Their data – from an insurer – covered 140,000 England sites from 1996-2015. Construction is slow in the UK: 597 days, versus 371 in the US, despite the former having smaller build sites.

Delays are endogenous. With higher demand growth, developers speed up projects to try to reach the market while it’s hot. But that motive is driven by competition. With less competition, they have less motive for speed. In UK locales with less available land, more restrictive regulation, or higher market power, demand shocks have less impact on delay.

Generalizing, they estimate that reducing regulatory restrictions by a standard deviation would decrease construction duration by 11%. Increasing land availability or decreasing market power by one S.D. would decrease construction time by 8%.

In the same session as Hilber et al, a few papers studied the market power of large landlords, who may have the ability to set prices monopolistically.

Fern Ramoutar used Chicago’s uniquely (?) partitioned rental market to study landlords’ market power. As evidence that rental markets are segmented, she showed that most moves take place within small geographic areas and (more surprisingly) among buildings of similar sizes. In Chicagoland, larger buildings (50+ units, typically high-rises) are the most expensive, and 2-4 flats the cheapest.

Once the market is sliced into neighborhood x building size segments, one landlord can plausibly dominate the segment. Using a staggered diff-in-diff, she finds that rents rise 5% following an acquisition of a competing property by a “dominant” landlord, relative to acquisition by a non-dominant landlord. (I’m not in IO, but I was confused that “dominant” was defined as any landlord with at least 1% of market share within a segment. Is that a plausible cutoff?)

Duke student Joe Fish studied Boston and Houston to get a broader sense of the importance of large landlords.

There’s some tension between Fish’s work and Ramoutar’s (which excludes renovation cases).

As a group, urban economists are natural YIMBYs. They’re mostly young and live in high-cost cities, they’re skeptical of ideological critiques of the market, and they’ve done enough welfare algebra to know that lowering the cost of housing is a big deal. But some of the most interesting papers of the conference offered cautions to YIMBY reformers.

Brad Ross and Zane Kashner show that NIMBYs aren’t lying when they say dislike the traffic brought by new neighbors. With incredibly refined TomTom data from Greater Boston, they’re able to estimate traffic flow and speed on every road segment in the region – and households’ willingness to pay to live on a a low-traffic street. They exploit shift-share congestion changes from 2010 to 2018 in a wild way: when an alternative route becomes congested, your street is likely to get more traffic, an increase that’s plausibly exogenous to any local change.

If you believe their math (which you have to take on faith, there’s no way any reviewer is going to understand what’s happening under the hood), the typical New Englander will pay 4% less for a house with 3,000 more cars per month. But there’s a lot of heterogeneity, and people sort accordingly: those with high tolerance for traffic end up on busy roads, those with very low tolerance on dead ends.

What does that mean for development? They estimate that upzoning has potentially large costs via traffic-generation. But concentrating that development at transit nodes and on main streets will decrease those costs, mostly because the people who live in those places care less about traffic. On the downside, this approach is less equitable, since poor people also live in places with disamenities like traffic.

James F. Hansen and Alicia N. Rimbaldi look at how Melbourne’s homes filter through the income distribution. It’s a classic YIMBY result: strict regulation has caused homes to filter upwards, with each successive owner having an income 15% higher than the previous one. Deregulating would lead to a 5% income decline at turnover.

But there’s a caution, too: the VicSmart local planning reforms (2012->2014) preempted local authority for some projects, which caused localities to tighten their own rules, rejecting the remaining projects at a higher rate.

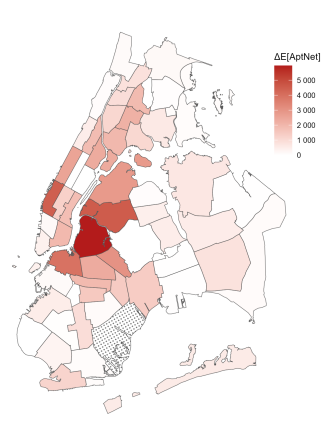

Daniel Lebret, Crocker H. Liu, and Maxence Valentin‘s research looks at the balance between FAR restrictions, tax exemptions, and inclusionary zoning in NYC. They use a structural model.

The caution comes in the replacement effect: Removal of cheap, old buildings increases unit rent a lot. In most of their simulations it outweighs the supply effect. That’s not how economists usually think about things (since a new and old apartment aren’t identical goods), but it is often how normie New Yorkers think about it.

Maybe greenfield growth – which destroys no housing – is underrated?

On the very bright side, their abstract concludes “allowing voluntary participation in incentive zoning schemes achieves nearly the same level of affordable housing production as mandatory policies but at substantially lower fiscal and infrastructure costs.” So maybe there’s no tradeoff between efficiency and equity after all?

James Macek formalizes my critique of the famous Hsieh and Moretti paper, which claimed huge productivity and income losses because of strict zoning. Macek finds plenty of benefits of upzoning: Eliminating minimum lot sizes is equivalent to raising the incomes of all poor Americans by 9%.

But affluent households, he estimates, liked their exclusive neighborhoods. They were willing to pay 28% more to live in a neighborhood with twice the average income. Without zoning, some of them will leave the high-productivity cities where they’ve clustered, dissipating the productivity benefits.

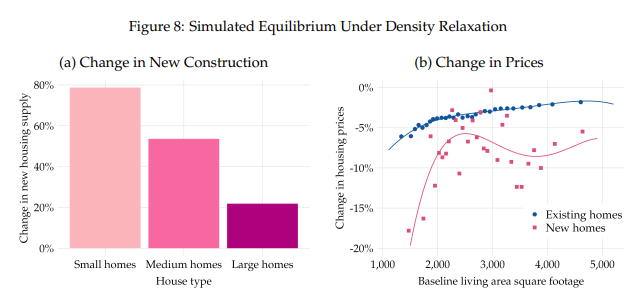

Like Macek, UGA professor Lei Ma finds that large-lot zoning has major distributional consequences, favoring the affluent. Small lots tend to host small homes. She uses a structural IO model to look at three policy experiments in the Atlanta metro area:

Many of the younger researchers, including Ma, Gold, and Ross, are clearly in tune with YIMBY ideas and eager to work on policy-relevant material. But they’re in a different professional world. There were only two people who attended both YIMBYtown and UEA this year (me and Michael Wiebe). That’s not a problem, per se, but there’s plenty of room for translational work. YIMBYs need solid research results. And economists need reality checks from people who know policy better than they do.

Hey Salim,

Thanks so much for shouting out my paper! When I was discussing Fern’s paper, I thought a bit about how to square what she finds (pretty large price effects from landlord acquisition) and what I find (small average effects; large effects for properties that are bought and subsequently renovated).

One way to square our results is to note that in her paper she finds only 5% of transactions meet her criteria for producing a “big” change in HHI, which are then the set of transactions she uses for her analysis. Given that she finds null price effects for large landlords who buy in properties outside their primary market, I think it’s reasonable to think that, if she ran her regressions on the full set of transactions, the *average* transaction wouldn’t move prices much. This would match what I find.

Likewise, if I zoomed in on a set of transactions that induced large changes to market structure, I wouldn’t be surprised if I found similar results to her. Interestingly, there’s an analogous paper in the broader mergers literature (most mergers don’t do much, but some have pretty big effects). The takeaway for policymakers would be to focus scrutiny in on transactions where there appears to be big changes in market structure.

– https://www.nber.org/papers/w31123

Re Lebret et al.:

>The caution comes in the replacement effect: Removal of cheap, old buildings increases unit rent a lot. In most of their simulations it outweighs the supply effect. That’s not how economists usually think about things (since a new and old apartment aren’t identical goods), but it is often how normie New Yorkers think about it.

Note that this is a composition effect. Rents of both new and old homes fall, but by replacement, average rents go up. This doesn’t really address whether a displaced renter faces higher or lower rents.