Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Spoiler Warning: This post contains minor spoilers about Season Two of Parks and Recreation, which aired nearly 10 years ago. Why have you still not watched it?

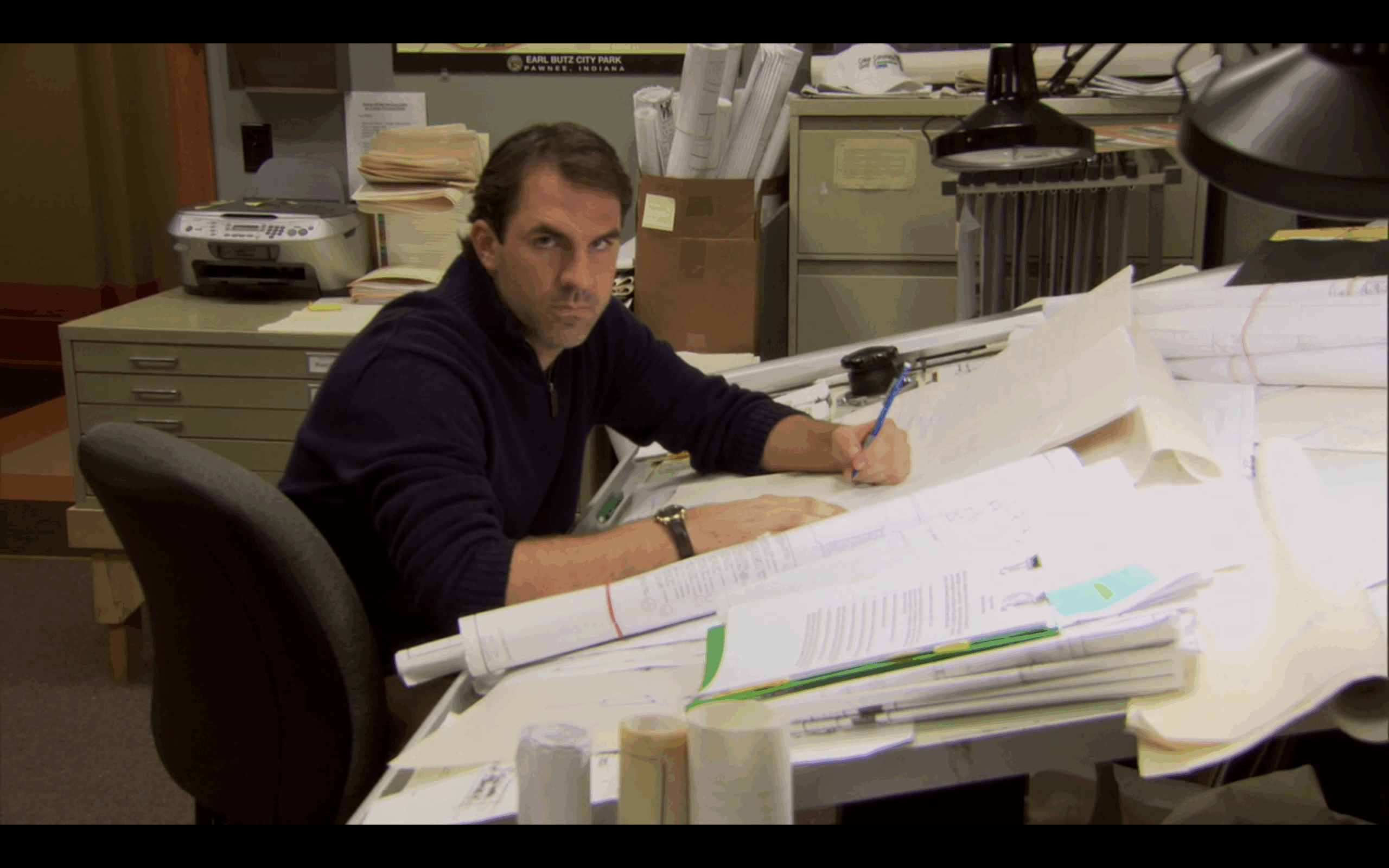

Lately I have been rewatching Parks and Recreation, motivated in part by the shocking discovery that my girlfriend never made it past the first season. The show is perhaps the most sympathetic cultural representation of local public sector work ever produced in the United States. The show manages to balance an awareness of popular discontent with “government” in the abstract— explored through a myriad of ridiculous situations—with the more mild reality that most local government employees are well-meaning, normal, mostly harmless people who care about their communities. This makes the character of Mark Brendanawicz, Pawnee’s jaded planner, all the more interesting.

It’s conspicuous that even in a show so sympathetic to local government, the city planner remains a cynical, somewhat unlikable character. Unlike Ron Swanson, Brendanawicz at one point meant well and has no ideological issues with government; he regularly suggests that he was once a true believer in his work, if only for “two months.” Yet unlike Leslie Knope, he didn’t choose government. In his efforts to win back Anne, Andy chides Brendanawicz as a “failed architect,” an insult which seems to stick. Brendanawicz ultimately leaves the show as an unredeemed loser: after taming his apparent self-absorption and promiscuity, he prepares to propose to Anne, only to have her preemptively break up with him. When the government shutdown occurs at the end of Season Two, Brendanawicz takes a buyout offer, and resolves to go into private-sector construction. Leslie, who had once adored him, dubs him “Brendanaquits,” and we never hear from Pawnee’s city planner again.

It isn’t hard to see why Brendanawicz was unceremoniously scrapped: he was ultimately a call-back to the harsher world of the first season, a world in which Leslie has deep character flaws that chart her on a course for regular disappointment (see also: early Michael Scott). In the brighter, friendlier world that began with Season Two, Brendanawicz had to go. But what does this say about city planning? Why is it that the only representation of city planning in popular culture over the past 25 years was such a sad, cynical man?

There are really two questions here: First, are planners in fact jaded? And second, why would the show’s audience be so comfortable with having planners presented this way? To dig into the first question, it’s useful to recognize upfront that most planners are smart, thoughtful, and well-meaning people. They have generally good ideas about how to improve their city and understand the deep flaws in the zoning ordinances they inherited. But there’s no point in denying that an existential cynicism hangs over the profession. Now more than ever, city planners are constrained by the whims of an angry public and politicians who want to avoid boat rocking at all costs. This cynicism-breeding disempowerment likely flows from the historically low view the general public has of city planners.

This turns us toward the second question: why is the TV viewing public comfortable with Pawnee’s city planner being so disillusioned? Note at this point that none of Pawnee’s other departments—sewage, police, libraries—are depicted in this way. As Tom Campbell points out in the Guardian, the cultural representation of planners as dotards and misanthropes is also a phenomenon across the pond as well. This is particularly odd, he adds, as it’s a far cry from the heroic image of the planner that prevailed during the pinnacle of high modernism in the 1950s and 60s. Campbell and the esteemed British historian of urban planning Peter Hall call for the return of this heroic image of planners as a way to attract the best and brightest to the field. Indeed, the current public view of city planners is perhaps unfair. Yet both Campbell and Hall fail to explore is precisely why the public image of planners collapsed so dramatically.

The trouble is that planning at its peak was a mixed bag at best. Early planning in the style of right-of-way procurement for roads, utilities, and sanitation as well as the construction of parks and public spaces was, for the most part, an unmitigated benefit to the public. Much of this work-a-day planning happened for centuries and often looked like a benign mixture of civil engineering and urban design. As planning expanded in the mid-twentieth century, it took on powers where success was hardly a guarantee and failure was a substantial risk. While early planning generally worked alongside markets and distributed decision making, high modernist planning necessarily involved privileging the plans of a special caste of technocrats. The profession at this stage situated itself in opposition to everything from markets, to apartments, to the poor and marginalized. While planning might have been sexy in this period of megaprojects and comprehensive land-use planning, as is any position with considerable power and a preference for strong egos (see also: architecture), it also inflicted incredible harm on our cities. That our profession is no longer able to attract those seduced by power, whatever their level of competence, does not strike me as obviously bad.

With public discontent already brewing, critics of urban planning such as Jane Jacobs rapidly gained support in channelling opposition to the field. This almost certainly wasn’t helped by the anti-democratic, top-down nature of much city planning activity. As conservative governments formed in the United States and the United Kingdom, political backing for centralized planning evaporated without any bottom-up support to fill the gap. In repentance and rest, city planners retreated, handing over much of their power to elected officials and angry members of the public. Most of us enter planning school and the profession with the goal of helping to build great cities. Yet today, much of planning is simply administering the land-use regulatory regime inherited from our high modernist predecessors. Most practicing planners I know will freely acknowledge that this system is deeply flawed. Is it any wonder that so many us turn into Brendanawiczs?

It’s time for a reckoning in planning. The public doesn’t like us and evidently we don’t like us either. None of this is going to change unless we have a frank discussion about the direction of the profession. Planning, and planners, have much to offer. The first step is to liberate ourselves from the arrogant and damaging excesses of planning at its “peak.” Megaprojects and root-and-branch revitalization have wreaked havoc on our cities; and attempts at comprehensive zoning and land planning and have devolved into a faustian bargain of more employment for planners in exchange for a life of fighting with members of the public, managing process, and filing paperwork. We are forcing ourselves to do work that we aren’t very good at, dictated by special interests, and against the wishes of the general public. Recall one of Brendanawicz’ final, miserable scenes on the show: Ron Swanson asks for a permit to build a shed, and Brendanawicz proceeds to pick apart his code violations.

In place of this tattered, cynicism-breeding planning we need a new liberal conception of the planner. Planning must be reframed as an intellectual adventure, a field in which the great planner accepts her epistemological limitations in the realm of land uses and densities and instead aims to understand, monitor, and report on the natural and unpredictable change underway in her city. Such a planner studies first real estate markets, environmental science, and urban design. This new planner, humbled but not incapacitated, should enjoy broad latitude to boldly plan out a flexible framework for infrastructure growth; she empowers, rather than resists, the organic development of cities, emphasizing the creation of beautiful and useful public spaces along the way. Above all, such a planner might emerge as a public intellectual; unafraid to take a stance, to explain her decisions on blogs and podcasts, and to educate (and learn from) the public about cities. The planning profession is about to enter Season Three. Will we adapt or be cut?

For future content and discussion, follow me on Twitter at @mnolangray.

What bothered me is that they never brought him back or hired another Planner to replace him. Pawnee, and the show, just gave up on Planning.

Don’t forget about Sam Pinkett in Wrong Mans! http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/profiles/55SqqMvQngJqRgQxz6d76XR/sam-pinkett

Small Town, Big Future!

An interesting–and hopeful–vision of the planner as a public intellectual. However, I fear that the inherent subordination of public sector planners to elected entities may always act as a constraint to action.