Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

I recently read about an interesting logical fallacy: the Morton’s fork fallacy, in which a conclusion “is drawn in several different ways that contradict each other.” The original “Morton” was a medieval tax collector who, according to legend, believed that someone who spent lavishly you were rich and could afford higher taxes, but that someone who spent less lavishly had lots of money saved and thus could also afford higher taxes. In other words, every conceivable set of facts leads to the same conclusion (that Morton’s victims needed to pay higher taxes). To put the arguments more concisely: heads I win, tails you lose. It seems to me that attacks on new housing based on affordability are somewhat similar. If housing is market-rate, some neighborhood activists will oppose it because it is not “affordable” and thus allegedly promotes gentrification. If housing is somewhat below market-rate, it is not “deeply affordable” and equally unnecessary. If housing is far below market-rate, neighbors may claim that it will attract poor people who will bring down property values. In other words, for housing opponents, housing is either too affordable or not affordable enough. Heads I win, tails you lose. Another example of Morton’s fork is the use of personal attacks against anyone who supports the new urbanism/smart growth movements (by which I mean walkable cities, public transit, or any sort of reform designed to make cities and suburbs less car-dominated). Smart growth supporters who live in suburbs or rural areas can be attacked as hypocrites: they preach that others should live in dense urban environments, yet they favor cars and sprawl for themselves. But if (like me) they live car-free in Manhattan, they can be ridiculed as eccentrics who do not appreciate the needs of suburbanites. Again, heads I win, tails you lose.

"These two homes straddle a 2010 zoning boundary change. The result: The house in duplex zoning converted into two homes, and the other converted into a McMansion that cost 80% more." - Arthur Gailes

A few weeks ago the Times reported that Lloyds Banking Group had purchased 45 new homes to let in Peterborough. This is part of a plan for Lloyds to own 50,000 homes by 2031. Given the median home in the City is now worth over 7 times the annual earnings of the typical resident, it is understandable why people would be upset. Indeed, why should a huge corporation be able to buy up all the properties in the City, when its own residents can’t afford to buy a new home there? However, this outrage is misdirected. Lloyds buying a few thousand homes over a decade will do nothing compared to the astronomical effect that NIMBYism and our planning system has had on house prices. The reason for this lies in a piece of legislation called the Town and Country Planning Act. This law abolished the automatic right to develop regulatory compliant housing, and added an additional stage of planning permission. As a result, it became mandatory for one to require state permission to build on one’s own land. Over the years this system has morphed into an almost quasi-right to block others’ construction giving residents the ability to stop others from moving into their area. This chiefly benefits homeowners – the people who engage the most in the planning system – since new houses will slow down the speed their own home’s value increases. The effect is that almost no houses get built. For example, in London during the 2010s we built around 25,000 houses per year; in the 1930s before the Planning Act was introduced that number was 61,500. Sadly housing just behaves like any other scarce asset. When there’s a shortage the sellers have more bargaining power and consumers are forced to pay more to buy the goods. […]

Over the years, I’ve heard a wide variety of arguments against new housing. One of them is the “mysterious foreign investor” argument. According to this theory, new urban housing will all be bought up by billionaire foreign investors, who will purchase the property and never rent it out, thus preventing the new housing from increasing supply. (I have rebutted the argument here).* A variation of the argument is that because some high-end housing is vacant, supply is therefore adequate to meet demand. (I have addressed this idea here). Another argument is that housing markets are segmented: that if you increase the supply at the top of the market, it will not help anyone who is not already at the top of the market. It seems to me that these arguments contradict each other: the first argument is based on the idea that high-end housing does affect the market as a whole (or would if rich people stopped using apartments as second homes); the second is based on the idea that high-end housing doesn’t affect the rest of the market at all. *In addition, I have recently published a much longer article in the New Mexico Law Review, discussing the pros and cons of high-end condos.

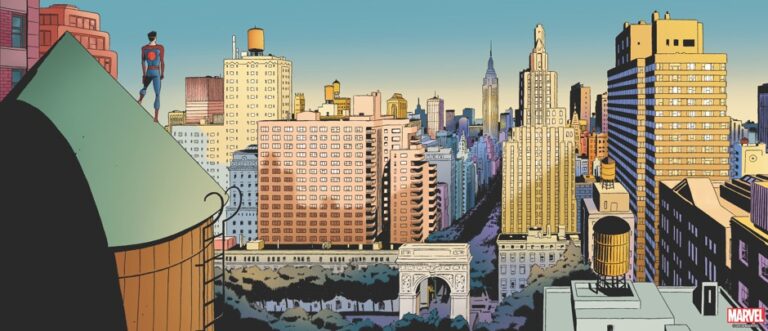

Nolan Gray plunges into the Sam Raimi "Spider-Man" trilogy to uncover the housing problems (and solutions) of expensive cities like New York.

Ever since zoning was invented in the 1920s, homeowners have argued that limits on density and on multifamily housing are necessary to protect property values. But today, urban NIMBYs seek to prevent new housing on the ground that new housing will lead to gentrification, which will in turn lead to increased property values, which in turn will lead to rising rents and displacement. Similarly, I often read that cities and suburbs shouldn’t have any new housing because they might become “too dense” or “overcrowded.” (Never mind that when there’s not enough housing to go around, excluded residents respond not by leaving the city, but by sleeping on the streets, thus making the city feel even more crowded). But at the same time, I also read that building new housing is futile, because it will all be bought up by foreign oligarchs, who (because they aren’t quite greedy enough to rent out their property) cause the housing to be lifeless and unoccupied. It is not quite clear to me how the city can be overcrowded and undercrowded at the same time, but evidently this view seems to be common.

During his last days in office, former Representative Jason Chaffetz must have forgotten he is supposed to be a fiscal conservative. His recent comments that members of Congress need $2,500 stipends to afford housing in DC reflect a complete ignorance of both the reasons for high housing prices and the best ways to lower those prices. Instead of treating the symptoms of skyrocketing housing prices, policymakers should be striking at the root: rent control, height limits, and burdensome zoning restrictions that discourage development. All of this turns on basic economics. Markets drive prices of goods and services down, but only if they are competitive. In many cases, existing interests try to prevent others from entering markets in order to protect their own bottom lines. Zoning regulations are often manipulated by interest groups, who hope to limit the allowed uses of land within a city and prevent future developments. Zoning essentially fixes the amount of available housing by discouraging developers from building more housing, ultimately driving housing prices up. Academic research places much of the blame for high housing costs on zoning––and this isn’t just limited to a single city or state. Edward Glaeser and Raven Saks of Harvard and Joseph Gyourko of the University of Pennsylvania examined Manhattan’s housing market estimate that new construction costs for housing are only about $300 per square foot, but that square foot tends to be rented out for $600, twice the cost at construction. Glaeser, Gyourko, and Saks write, quite intuitively, that “this would seem to offer an irresistible opportunity for developers.” But it’s zoning regulations that prevent developers from coming in to build more homes (which ultimately lowers housing prices), despite market incentives. Even though there is a deafening clamor for more housing, as evidenced by rising prices, building takes so long in […]