Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

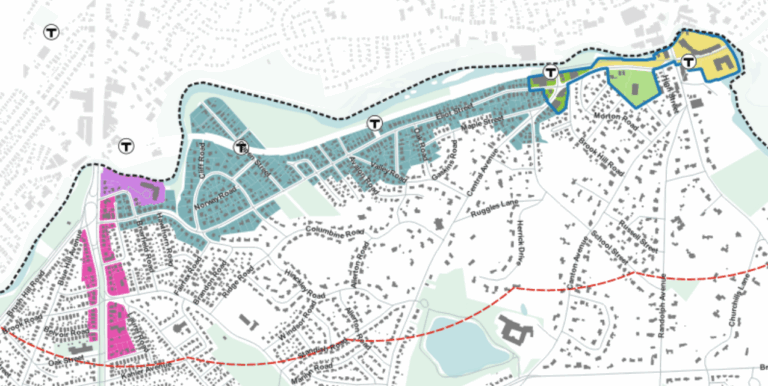

“Wow!” the reporter said, “I knew you from Milton, but I didn’t know you were from East Milton. Tell me what it feels like?” Well, until last week it was not that dramatic. East Milton is an old railroad-commuter neighborhood favored by affluent Boston Irish. It’s separated from the City of Boston by the Neponset River estuary and from the rest of Milton by a sunken interstate highway that makes it more congested and big-city than the rest of town. MBTA Communities In January 2021, Massachusetts passed the first transit-oriented upzoning law of the YIMBY era, now called “MBTA Communities,” “MTBA-C”, or “Section 3A”. Implementing regulations assigned a multifamily zoning capacity to each town. Milton was always going to be one of the toughest cases for MBTA Communities. The northern edge of town is served by the Mattapan Trolley, which John Adams rode to the Boston Tea Party links up to the Red Line at Ashmont. The trolley makes Milton a “rapid transit community”, which means it has to zone for multifamily units equal to 25% of its housing stock. Among the dozen towns in the rapid transit category, Milton is the only one where less than a quarter of current housing units are multifamily; it also has few commercial areas to upzone. East Milton dissents East Milton voters went to the polls on Wednesday and led a referendum rebuke of the plan. In Ward 7, it wasn’t close: 82% opposed the rezoning. The Boston Globe offered a helpful breakdown of the surprisingly varied voting: There are several hypotheses as to why the neighborhood went against rezoning so hard, all probably played a role. East Milton was assigned more than half the net new multifamily zoning capacity despite lacking good transit access. The neighborhood has been in a contentious, multiyear […]

Some people accept the idea that restrictive land use policy is just as bad as all the research suggests, but persist in supporting the status quo. They argue that if a community chooses to regulate its built environment, that choice should be respected as having moral weight because it’s the outcome of a democratic process. This argument, though, is as logically confused as it is normatively problematic. And in the following few lines, I intend to demonstrate exactly why. No decision making process is value neutral. Whatever way we choose to go about collective decision making, we will always privilege certain voices over others. Institutions beget outcomes and the internal logic of our institutions will always favor some outcomes (and therefore voices) over others. The same individuals with the same preferences asked to make the same decisions through different procedures will produce wildly different outcomes. Imagine a U.S. Presidential election based on the popular vote or representation in the U.S. Senate proportional to state population and you should begin to see how the public will is as much a product of procedure as it is aggregated individual preference. Taking the Bay Area as a land use specific example, our system heavily favors the voices of incumbent homeowners to the detriment of everyone else. Land use decisions take place at the municipal level which–given the fact that we have 101 different municipalities–is a hyper local affair. When a new development is proposed, it only takes a handful of angry neighbors to impact decision making. Were land use set at a higher level of government, the typical number of people that get angry over an individual project would be far less effective at killing new housing. Fifty angry homeowners might matter to the Palo Alto City Council, but they’d be quite a […]