Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In a recent post, I revealed the 91 large cities and counties that consistently fail to report complete data to the federal Building Permit Survey (BPS). But what about smaller jurisdictions, which often have weak record-keeping and slim staffs – and what about states made up of many such small jurisdictions? The gold standard for counting housing units is the Decennial Census. That shows that the number of homes in Massachusetts grew from 2,622,000 in 2000 to 2,808,000 in 2010 to 2,998,000 in 2020. Even though building permits do not always result in completed homes, local reports and Census Bureau interpolations fall well short: It’s possible that some building permits pulled in 2007-2009 were delayed by the Great Recession but completed after the 2010 census. Taking the twenty-year period together, the BPS (2000-2019) is only picking up 84 percent of completed homes – not to mention those that are permitted but abandoned. Looking ahead, Gov. Healey’s administration has estimated (poorly) that the commonwealth needs 222,000 new homes by 2035. How does that compare to recent production? We don’t have a 2024 Census. But if we assume that reported 2015-2024 building permits turn into housing at the same rate that 2000-2019 building permits did, we can get a working estimate. The BPS reports 167,000 Bay State building permits from 2015 through 2024 (with extrapolation for December, 2024). That means that something closer to 199,000 new homes were likely completed in that period. If that’s true, then the administration’s “housing need” estimate is just 12% higher than recent construction – which has been inadequate to prevent a huge upswing in rents and prices.

“Wow!” the reporter said, “I knew you from Milton, but I didn’t know you were from East Milton. Tell me what it feels like?” Well, until last week it was not that dramatic. East Milton is an old railroad-commuter neighborhood favored by affluent Boston Irish. It’s separated from the City of Boston by the Neponset River estuary and from the rest of Milton by a sunken interstate highway that makes it more congested and big-city than the rest of town. MBTA Communities In January 2021, Massachusetts passed the first transit-oriented upzoning law of the YIMBY era, now called “MBTA Communities,” “MTBA-C”, or “Section 3A”. Implementing regulations assigned a multifamily zoning capacity to each town. Milton was always going to be one of the toughest cases for MBTA Communities. The northern edge of town is served by the Mattapan Trolley, which John Adams rode to the Boston Tea Party links up to the Red Line at Ashmont. The trolley makes Milton a “rapid transit community”, which means it has to zone for multifamily units equal to 25% of its housing stock. Among the dozen towns in the rapid transit category, Milton is the only one where less than a quarter of current housing units are multifamily; it also has few commercial areas to upzone. East Milton dissents East Milton voters went to the polls on Wednesday and led a referendum rebuke of the plan. In Ward 7, it wasn’t close: 82% opposed the rezoning. The Boston Globe offered a helpful breakdown of the surprisingly varied voting: There are several hypotheses as to why the neighborhood went against rezoning so hard, all probably played a role. East Milton was assigned more than half the net new multifamily zoning capacity despite lacking good transit access. The neighborhood has been in a contentious, multiyear […]

A headline in the Boston Globe screams: “Boston’s new luxury towers appear to house few local residents.” The headline is based on a report by the leftist Institute for Policy Studies, which claims that in twelve Boston condo buildings, “64 percent do not claim a residential exemption, a clear indication that the condo owners are not using their units as their primary residence.”* The report accordingly concludes that these buildings do not “address Boston’s acute affordable housing crisis.” This seems to be another version of the common “foreign buyers” argument: that new housing does not hold down rents, because it will all be bought up by rich foreigners who will let the units sit unoccupied forever. Although the report does not explicitly endorse restrictive zoning, it does urge the city to require new residential buildings to be carbon-neutral- a rule that might make residential construction more difficult. But this inference would be wrong. If you own a condominium, you have three choices: (1) to live in it; (2) to sit on it and lose money on your mortgage; or (3) to rent it out. Obviously, you make the most money through choice (3)- renting out the condo. So even a condo owner who does not choose option (1) has a strong incentive to adopt choice (3). Thus, it seems likely that at least some, if not all, of the condos will be rented out, thus increasing rather than decreasing regional housing supply, which in turn will have a positive effect on housing prices. *The residential exemption saves Boston homeowners up to $2500 per year on their tax bill. I would think that at least some owner-occupants are unaware of or forget to file for this exemption- but since I have no idea how common this is, I am reluctant […]

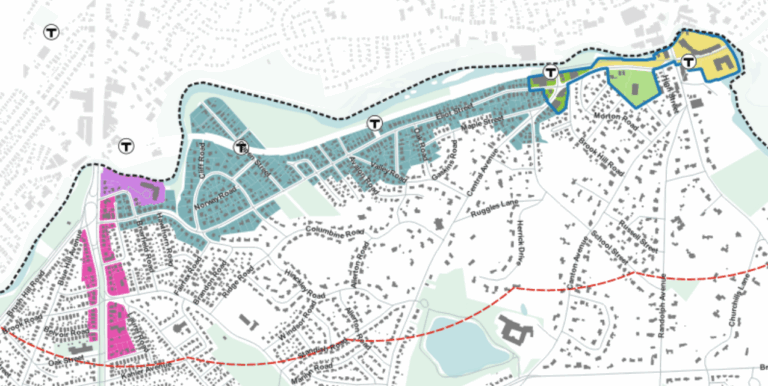

Public transportation service provision is changing. As I already have mentioned in this post at Caos Planejado, microtransit services are growing in many cities around the world and one of the forefront companies on this field is Bridj, operating in Boston since June 2014 and Washington DC since May 2015. I had the opportunity to interview David Block-Schachter, Chief Scientist of Bridj at Bridj’s office in Boston last October. Check it out: Marcos Paulo Schlickmann: Could you tell a little about yourself and your inspiration to work in this field? David Block-Schachter: About 8 years after finishing my bachelor’s I went back to school to do a PhD in transportation at MIT. After the PhD I worked for the MBTA as their Director of Research and Analysis to understand how they can use their data to improve operations. After that I joined Bridj. We wanted to improve mass transit generally, and looked at the issues here in Boston as our first focus. And obviously my background helped too. We also looked at informal transit systems all around the world. When I went to Rio I noticed how the buses are at a disadvantage, because the traffic itself is so unreliable that if you have a car you would prefer to be stuck on traffic in your car than in the bus. So we asked ourselves: “How can we use technology to combine the direct service associated with small vehicles with the good level of service we see in mass transit systems in America and Europe without inheriting the defaults and drawbacks of each system?” And the main advantage of direct trips instead of changing vehicles can be addressed by technology. MPS: As we see on the map depicting Bridj’s service areas, the company runs buses in 3 main areas with two main lines: Allston/Coolidge […]

That’s one takeaway from a paper sent to me by one of its co-authors, Andy Garin, at MIT, on the effects of the end of rent control in Massachusetts in 1995 on property values in Cambridge. Fascinating topic, and much thanks to Andy for sending it to me – it’s always nice when other people write my blog posts for me! Andy assures me that they “went through great pains to make sure our results do, in fact, have a causal interpretation, and meaningful,” but as always, I don’t have the statistical background to fisk its methods, so feel free to go at it in the comments. Here’s the abstract of the working paper, available on NBER, called “Housing Market Spillovers: Evidence from the End of Rent Control in Cambridge Massachusetts”: Understanding potential spillovers from the attributes and actions of neighborhood residents onto the value of surrounding properties and neighborhoods is central to both the theory of urban economics and the development of efficient housing policy. This paper measures the capitalization of housing market spillovers by studying the sudden and largely unanticipated 1995 elimination of stringent rent controls in Cambridge, Massachusetts that had previously muted landlords’ investment incentives and altered the assignment of residents to locations. Pooling administrative data on the assessed values of each residential property and the prices and characteristics of all residential transactions between 1988 and 2005, we find that rent control’s removal produced large, positive, and robust spillovers onto the price of never-controlled housing from nearby decontrolled units. Elimination of rent control added about $1.8 billion to the value of Cambridge’s housing stock between 1994 and 2004, equal to nearly a quarter of total Cambridge residential price appreciation in this period. Positive spillovers to never-controlled properties account for more half of the induced price appreciation. Residential investments can […]

Old Urbanist is one of my favorite urbanist blogs (and not just because of the name), and Charlie’s got a post up about Boston that I think has a good market urbanist lesson in it. He describes how the formerly elevated Central Artery, buried by the Big Dig, was replaced with a park, with nobody seeming to understand that highways’ damaging effects comes from what they demolish – buildings, and lots of them. An excerpt: With no one able to agree on anything in particular, the environmentalists of the late 1980s stepped in to offer the compelling alternative of nothing, packaged under the name “open space,” and obtained a requirement that 75% of the land above the buried highway be set aside for it. The realization has only recently sunk in that even “nothing” must be paid for, as the conservancy tasked with maintaining the Greenway has now proposed taxing abutting property owners to raise funds, the largesse of Boston’s citizens, already maintaining several very large parks in close proximity, apparently falling short. Thus, land that, under private ownership, might have provided millions of dollars in tax revenue to the city, and hosted thousands of jobs and apartments, has become a money pit. The missed opportunity is even more tragic given that one of the very few neighborhoods in the United States laid out in truly traditional fashion, the North End, with its narrow winding streets and attractive mid-rise architecture, sits right next to the Greenway. The blank side walls of 19th century townhouses, their adjoining buildings demolished for the Artery in the 1950s, cry out to be extended southwards by new neighbors. The elusive vision is right there, a reality, not a fantasy, yet somehow it escaped the attention of Boston’s elected officials, planners, architects and the public itself. […]

1. Hamburg’s newly-revitalized port could get a completely privately-funded cable car line, if the city allows it. 2. Quincy, Mass., a few T stops away from downtown Boston, is getting a new downtown from a private developer, replete with infrastructure and dense development. It’s unique, however, in that the city supposedly isn’t giving the developer huge tax breaks and infrastructure subsidies (more here). Here is an article about a previous project by the same developer, Street-Works. Environmentalists, predictably, are perturbed. In any case, the project sounds promising, though I guess the devil’s in the details. Anyone know anything more about it? 3. In Brooklyn, near a bridge, almost 150 years old, doesn’t have a roof! – adaptive reuse opportunities like Dumbo’s Tobacco Warehouse don’t come along too often, even in New York, so it’s unfortunate that developers are only being allowed to build to two stories (if they’re allowed to build at all). 4. Other cities seem to have plenty of people willing to do it for free, but Berkeley’s City Council actually subsidizes its BRT-hating NIMBYs to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars under the guise of the “Community Environmental Advisory Committee.” It’s a shame that every metro area doesn’t have a transit critic like the Drunk Engineer, who I think is the best transit commentator in the blogosphere. 5. Randal O’Toole on TriMet, Portland’s transit agency, and its mismanagement. 6. “A Requiem for ‘High-Speed Rail’,” from New Geography.

1. Maps of sprawl and gentrification in Detroit, St. Louis, Chicago, and Boston. At first the picture looks bleak for cities, but Jesus – even downtown Detroit is growing! (More here.) 2. A real, live Texan (just kidding – he lives in Austin) replies to O’Toole on parking. 3. Why aren’t (more) urbanists cheering on Jerry Brown’s attempt to kill sprawl-inducing California redevelopment agencies? (Streetsblog SF/LA, I’m looking at you!) 4. NY lawsuit alleges that LEED standards are meaningless, and Charlie at Old Urbanist takes the opportunity to review the case against America’s most popular “greenness” metric. 5. This is awesome: The DC Office of Zoning makes the code and all the overlays accessible on Google Maps. Is there any other city with anything like it?

I started reading Fogelson’s Downtown with the intention of learning more about elevated trains, and though I’ve been slightly disappointed in that regard (more to come on that after I finish and attempt a more comprehensive review), he does include a lot of interesting history. I’m posting this more so that I remember it, but the first paragraph offers an interesting rejoinder to those who say that els could never be viable because of the blight factor, and the Second Avenue elevated line makes a cameo towards the end: In view of the longstanding and deep-seated opposition to elevated railways, the construction of elevated highways is more than a little puzzling. This opposition has grown so vociferous that by the 1920s most Americans had come to believe that elevated railways should never have been built in the first place. Despite assurances by several leading engineers that it was possible to build els that were quiet, clean, and attractive (and would not reduce property values), they remained convinced that under no circumstances should any more be constructed. The cities should not only stop building elevated railways, many Americans insisted; they should start demolishing them. This idea, which had surfaced in the first two decades of the century, caught on in the 1920s, especially in New York and Boston. In favor of it were abutting businessmen and property owners, who believed that the removal of the els would improve trade and raise values. Allied with them were public officials (among them Julius Miller, borough president of Manhattan and chief advocate of the West Side Elevated Highway), who thought the demolition of the els would foster economic development; traffic experts (including New York City Police Commissioner Enright, another advocate of elevated highways), who assumed that the removal of the elevated structures would facilitate […]

While doing research for something totally unrelated, I came across this paper by Asha Weinstein (.pdf) on parking policy in Boston in the 1920s. One of the things she (?) discusses is the political feasibility of charging for the right to park downtown: Despite this general consensus, however, there was no shared view on what might constitute effective downtown parking policies. On the one hand, most people supported modest policy changes such as modifying existing regulations, improving motorist compliance with those regulations, or building more off-street parking, but even the strongest advocates of such policies never claimed they would significantly impact congestion. At the other end of the spectrum, a few people called for the drastic options of banning all street parking during business hours, or charging a fee to park on the streets. These proposals were touted as highly effective congestion relief, but they garnered little serious support and generated storms of opposition, and were never treated as serious proposals by the larger community. […] So you might think to yourself, “Banning parking entirely seems kind of draconian, but pricing parking at least sounds rational.” But you’re not a Bostonian living in 1926: Even less popular than a parking ban was the idea of a parking fee. In January 1926, this new approach to parking was proposed by a sub-committee of Boston’s Ways and Means Committee and Mayor Nichols. The proposal called for keeping the existing parking regulations, but charging drivers an annual fee of $5 to $10 for the right to park on city streets. The opposition from business and automobile advocacy groups was decisive and adversarial. All the city’s newspapers ran scathing articles. For example, the high-society Transcript immediately published an editorial warning that the proposed fee would be counterproductive as a revenue-generator because it would likely […]