Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

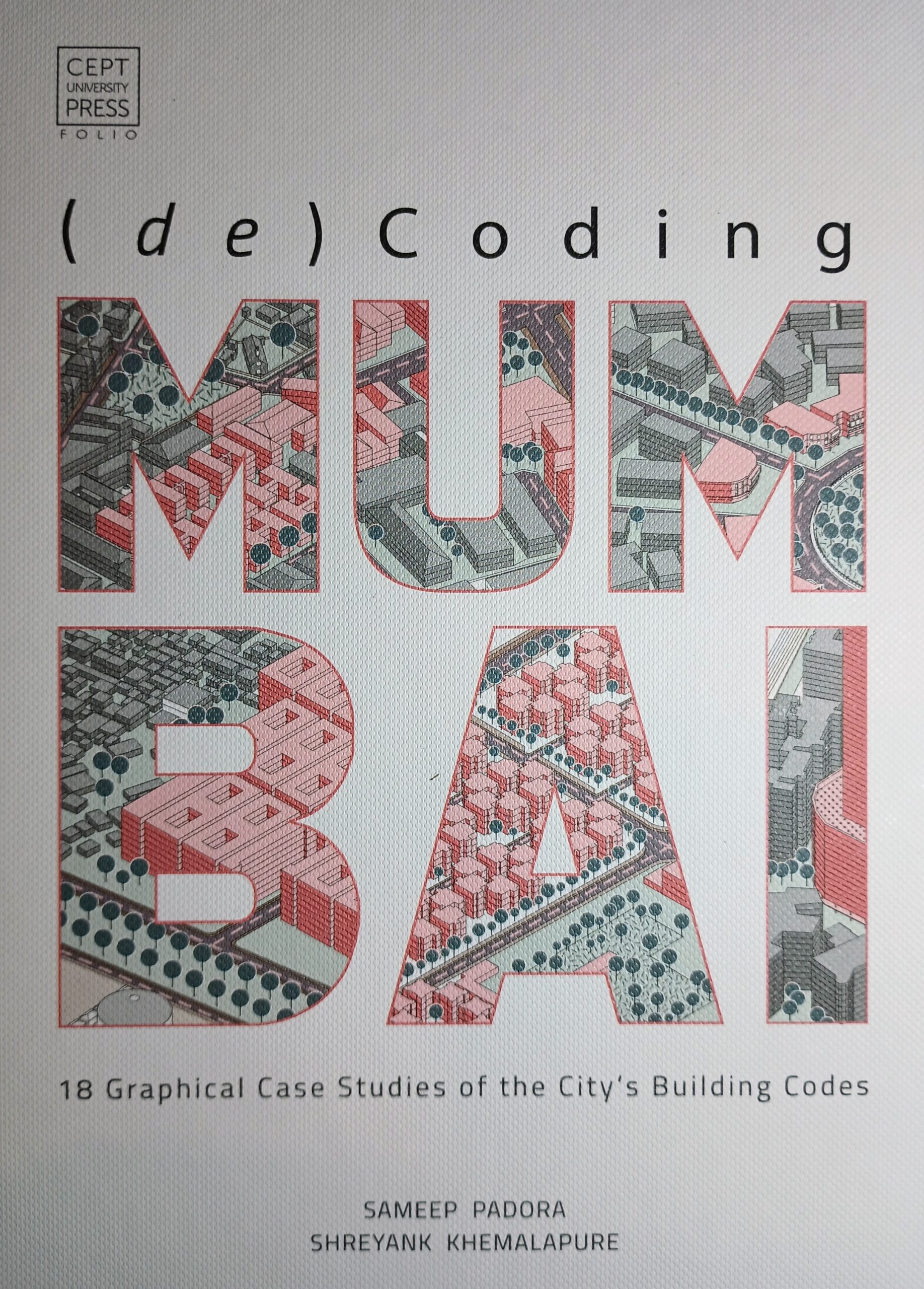

In Mumbai, there is a specific type of architect who has become the interpreter of regulations and there are those architects who are aestheticians working on building skins. As much as there is convenience in this split, it has taken away a big part of the agency of the architects in the city.

In two previous posts, I’ve raised questions about the competitiveness of missing middle housing. This post is more petty: I want to challenge the design rigidities that Daniel Parolek promotes in Missing Middle Housing. Although petty, it’s not irrelevant, because Parolek recommends that cities regulate to match his design goals, and such regulations could stifle some of the most successful contemporary infill growth. Parolek’s book suffers from his demands that missing middle housing match his own tastes. For instance, he has a (Western?) bias against three-story buildings. Having grown up in the Northeast, I think of three stories as the normal and appropriate height for a house. To each his own – but Parolek’s constant insistence on this point offers aid to neighborhood defenders who will be happy to quote him to make sure three-story middle housing remains missing. The house in the doghouse No form is in Parolek’s doghouse as much as the “tuck-under” townhouse, an attached house with a garage on the first floor. This is clearly a building that builders and buyers love: “If your regulations do not explicitly prohibit it, it will be what most builders will build” (p. 140). In fact, tuck-under townhouses are probably the most successful middle housing type around. In lightly-regulated Houston, builders small and large have been building townhouses, sometimes on courtyards perpendicular to the road. Parking is tucked. Townhouses are usually three stories tall (bad!), sometimes four. A few are even five stories. Their courtyards are driveways (also bad!). In a very different context – Palisades Park, NJ – tuck-under duplexes are everywhere. Their garages are excessive thanks to high parking minimums, but the form has been very successful nonetheless. These examples are not to be dismissed lightly: these are some of the only cases where widespread middle housing is […]

In yesterday’s post, I showed that missing middle housing, as celebrated in Daniel Parolek’s new book, may be stuck in the middle, too balanced to compete with single family housing on the one hand and multifamily on the other. But what about all the disadvantages that middle housing faces? Aren’t those cost disadvantages just the result of unfair regulations and financing? Indeed, structures of three or more units are subject to a stricter fire code. It’s costly to set up a condo or homeowners’ association. Small-scale infill builders don’t have economies of scale. Those, and the other barriers to middle housing that Parolek lays out in Chapter 4, seem inherent or reasonable rather than unfair. In particular, most middle housing types cannot, if all units are owner-occupied, use a brilliant legal tradition known as “fee simple” ownership. Fee simple is the most common form of ownership in the Anglosphere and it facilitates clarity in transactions, chain of title, and maintenance. Urbanists should especially favor fee simple ownership of most city parcels because it facilitates redevelopment. Consider a six-plex condominium nearing the end of its useful life: to demolish and redevelop the site requires bringing six owners to agreement on the terms and timing of redevelopment. A single-owner building can be bought in a single arms-length transaction. It’s no coincidence that the type of middle housing with the greatest success in recent years – townhomes – can be occupied by fee-simple owners, combining the advantages of owner-occupancy with the advantages of the fee simple legal tradition. Many middle housing forms enjoy their own structural advantage: one unit is frequently the home of the (fee simple) owner. By occupying one unit, a purchaser can also access much lower interest rates than a non-resident landlord. (This is thanks to FHA insurance, as Parolek […]

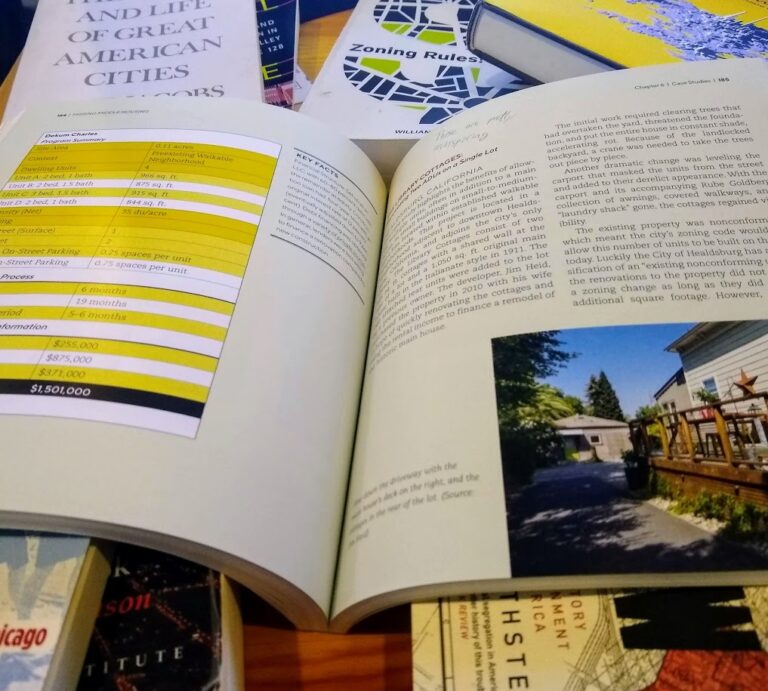

Everybody loves missing middle housing! What’s not to like? It consists of neighborly, often attractive homes that fit in equally well in Rumford, Maine, and Queens, New York. Missing middle housing types have character and personality. They’re often affordable and vintage. Daniel Parolek’s new book Missing Middle Housing expounds the concept (which he coined), collecting in one place the arguments for missing middle housing, many examples, and several emblematic case studies. The entire book is beautifully illustrated and enjoyable to read, despite its ample technical details. Missing Middle Housing is targeted to people who know how to read a pro forma and a zoning code. But there’s interest beyond the home-building industry. Several states and cities have rewritten codes to encourage middle housing. Portland’s RIP draws heavily on Parolek’s ideas. In Maryland, I testified warmly about the benefits of middle housing. I came to Missing Middle Housing with very favorable views of missing middle housing. Now I’m not so sure. Parolek’s case for middle housing relies so much on aesthetics and regulation that it makes me wonder whether middle housing deserves all the love it’s currently getting from the YIMBY movement. Can middle housing compete? Throughout the book, Parolek makes the case that missing middle construction cannot compete, financially, with either single-family or multifamily construction. That’s quite contrary to what I’ve read elsewhere. In a chapter called “The Missing Middle Housing Affordability Solution”, Daniel Parolek and chapter co-author Karen Parolek write: The economic benefits of Missing Middle Housing are only possible in areas where land is not already zoned for large, multiunit buildings, which will drive land prices up to the point that Missing Middle Housing will not be economically viable. (p. 56) On page 81, we learn, It’s a fact that building larger buildings, say a 125-150 unit apartment […]

We are blessed and cursed to live in times in which most smart people are expected to have an opinion on zoning. Blessed, in that zoning is arguably the single most important institution shaping where we live, how we move around, and who we meet. Cursed, in that zoning is notoriously obtuse, with zoning ordinances often cloaked in jargon, hidden away in PDFs, and completely different city-to-city. Given this unusual state of affairs, I’m often asked, “What should I read to understand zoning?” To answer this question, I have put together a list of books for the zoning-curious. These have been broken out into three buckets: “Introductory” texts largely lay out the general challenges facing cities, with—at most—high-level discussions of zoning. Most people casually interested in cities can stop here. “Intermediate” texts address zoning specifically, explaining how it works at a general level. These texts are best for people who know a thing or two about cities but would like to learn more about zoning specifically. “Advanced” texts represent the outer frontier of zoning knowledge. While possibly too difficult or too deep into the weeds to be of interest to most lay observers, these texts should be treated as essential among professional planners, urban economists, and urban designers. Before I start, a few obligatory qualifications: First, this not an exhaustive list. There were many great books that I left out in order to keep this list focused. Maybe you feel very strongly that I shouldn’t have left a particular book out. That’s great! Share it in the comments below. Second, while these books will give you a framework for interpreting zoning, they’re no substitute for understanding the way zoning works in your specific city. The only way to get that knowledge is to follow your local planning journalists, attend local […]

This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding. This is how Jane Jacobs opened her 1961 classic “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”. It wouldn’t be an inappropriate opener for Alain Bertaud’s upcoming “Order Without Design”. While Jacobs was an observer of how cities work and a contributor to new concepts in urban economics, Bertaud goes a step further. His book brings economic logic and quantitative analysis to guide urban planning decision-making, colored by a hands-on, 55-year career as a global urban planner. His conclusion? The urban planning practice is oblivious to the economic effects of their decisions, and eventually creates unintended consequences to urban development. His goal with this book is to bring economics as an important tool to the urban planning profession, and to bring economists closer to the practical challenge of working with cities. Maybe you have not heard about Alain Bertaud before: at the time I am writing this article, he has only a few articles published online, no Wikipedia page or Twitter account, and some lectures on YouTube – and nothing close to a TED talk. The reason is that instead of working on becoming a public figure, Bertaud was actually doing work on the ground, helping cities in all continents tackle their urban development problems. His tremendous experience makes this book that delves into urban economics surprisingly exhilarating. As an example, Bertaud shows a 1970 photo from when he was tracing new streets in Yemen using a Land Rover and the help of two local assistants who look 12 years old at most, a depiction of a real-life Indiana Jones of urban planning. In this book, mainstream urban planning “buzzwords” such as Transit-Oriented Development, Inclusionary Zoning, Smart Growth and Urban Growth Boundaries are challenged with economic analysis, grounded on […]

No one writer of the last 60 years has influenced urban planning and thinking as much as Jane Jacobs. It seems like just about everyone who has ever set foot in a major city has read The Death and Life of Great American Cities and most professional urban planners have embraced at least part of her ideas. But that was not the only book she wrote and the others deserve attention from urbanists. First published in 1984, Cities and the Wealth of Nations was her last book to focus on cities and her second concerned with economics. Conceived at the height of 1970s stagflation, Jacobs brought her considerable polemical skills to bear on macroeconomics and elaborated on the observations in The Economy of Cities. In that book she theorized that economic expansion in cities was driven by trade, innovation and imitation in a process she called “import replacement”. In this one she extended the idea, arguing that cities and not nation-states are the real basic units of macroeconomic life. She also examined how the economic expansion affected regions in differing geographic proximity and how import-replacement and the wealth generated by it can be used in ways that ultimately undermine the abilities of cities to create wealth, which she called transactions of decline. Import-replacement is one of Jacobs’ more controversial ideas, partially because it seems similar to a discredited development policy called import substitution and partially because her evidence is largely anecdotal, as Alon Levy wrote back in 2007. Nevertheless it’s the centerpiece of Jacobs’ economic theories. And dismissing her work based on a lack of conventional credentials ignores her entire rise to fame and influence. Two important things distinguish import-replacement from import-substitution. Substitution is a national policy pursued by governments with taxes, tariffs and subsidies while replacement is a process […]

The era of liberals writing e-books about market urbanism is upon us! I knew about Matt Yglesias’ upcoming “Kindle Single” The Rent is Too Damn High, but Ryan Avent’s The Gated City took me by surprise. Ryan’s book has a “print length” of 90 pages, costs $1.99, and despite the name “Kindle Single,” can be downloaded to pretty much any computer or smart phone. I haven’t read it yet, but I’m going to download it soon. Consider this an open thread to discuss the book(s).

A paragraph on what we might today call “good transit” in Railroaded: What distinguished railroads from the natural geography through which they ran was their centrality to measures of value; they transformed everything around them. There is no such thing as a badly placed river on a mountain, although humans may wish they were located elsewhere. They are wehre they are, but engineers located railroads for human purposes. There were good locations and bad. To determine the line between “the utterly bad and the barely tolerable” in railway location, Wellington relied on a second abstract measure: the dollar. Wellington thought engineering should not be considered the art of construction but rather “the art of doing that well with one dollar, which any bungler can do with two after a fashion.” How to build a railroad was widely studied, but “the larger questions of where to build and when to buil, and whether to build them at all” had been neglected. Hm, if only there were some process for building infrastructure that “relied on the dollar”…

So I bought Richard White’s Railroaded based on the interview Emily blogged about earlier, and so far I’m enjoying it. It can be a bit polemical (“He was an eclectic hater who hated people who often hated one another”) and by page 34 I’ve already gotten lost a few times in railroad finance jargon, but hopefully that’ll ease as I get further in the book. Anyway, in the beginning the author makes reference to commonalities between today’s financial mess(es) and the intercontinentals. Here’s the first one I saw: The Central Pacific and other transcontinental railroads, their bankers, and the syndicates together lured investors, who had first ventured into the financial markets during the Civil War, along the financial gangplank one small step at a time. Investors proceeded from government bonds to government-secured railroad bonds, to convertible bonds, to mortgage bonds vouched for by the same people who sold the government bonds, to a whole array of financial instruments, and from there, potentially, into the drink.