Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, revolutionised urban theory. This essay kicks off a series exploring Jacobs’ influential ideas and their potential to address today’s urban challenges and enhance city living. Adam Louis Sebastian Lehodey, the author of this collection of essays, studies philosophy and economics on the dual degree between Columbia University and SciencesPo Paris. Having grown up between London and Paris, he is energised by the questions of urban economics, the role of the metropolis in the global economy, urban governance and cities as spontaneous order. He works as an Applied Research Intern at the Mercatus Center. Since man is a political animal, and an intensely social existence is a necessary condition for his flourishing, then it follows that the city is the best form of spatial organisation. In the city arises a form of synergy, the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, for the remarkable thing about cities is that they tap into the brimming potential of every human being. In nowhere but the city can one find such a variety of human ingenuity, cooperation, culture and ideas. The challenge for cities is that they operate on their own logic. Cities are one of the best illustrations of spontaneous order. The city in history did not emerge as the result of a rational plan; rather, what the city represents is the physical manifestation of millions of individuals making decisions about where to locate their homes, carry out economic transactions, and form intricate social webs. This reality is difficult to reconcile with our modern preference for scientific positivism and rationalism. But for the Polis to flourish, it must be properly understood by the countless planners, reformers, politicians and the larger body of citizens inhabiting the space. Enter Jane […]

Last year disappointed pro-housing advocates in Colorado, as Governor Polis’s flagship reform was defeated by the state legislature. But Polis and his legislative allies tried again this year, and yesterday the governor signed into law a package of reforms which cover much of the ground of last year’s ill-fated HB23-213. HB24-1152 is an ADU bill. It applies to cities with populations over 1000 within metropolitan planning areas (so, the Front Range – home to most of Colorado’s major cities – along with Grand Junction), and CDPs with populations over 10,000 within MPOs. Within those jurisdictions, the law requires the permitting of at least 1 ADU per lot in any zone that permits single-family homes, without public hearings, parking requirements, owner-occupancy requirements, or ‘restrictive’ design or dimensional standards. The law also appropriates funds available for ADU permit fee mitigation, to be made available to ADU-supportive jurisdictions which go beyond compliance with the law to make ADUs easier to build (including jurisdictions not subject to the law’s preemption provisions). HB24-1304 eliminates parking minimums for multifamily and mixed-use buildings near transit within MPOs (though localities can impose parking minimums up to 1 space per unit for buildings of 20+ units or for buildings with affordable housing, if they issue a fact-based finding showing negative impacts otherwise). This bill was pared down in the Senate and would originally have eliminated parking requirements within MPOs entirely. HB24-1313 is a TOD and planning obligations bill. The bill:– Designates certain localities as ‘transit-oriented’ (if they are within MPOs, have a population of 4,000+, and have 75+ acres total either within ¼ mile of a frequent transit route or within ½ mile of a transit station – in effect, 30 or so localities along the Front Range).– Assigns all transit-oriented communities (TOCs) housing opportunity goals, which are simply […]

As anticipated by the “radical agreement” among the parties and justices at oral argument, the Supreme Court’s recently released decision in Sheetz v. County of El Dorado put to rest the question of whether legislatively-imposed land use permit conditions are outside the scope of the takings clause. The unanimous ruling confirms the common-sense proposition that a state action cannot evade constitutional scrutiny simply because it’s a law of general application rather than an administrative decree, and subjects conditions on building permits – whether monetary or not – to the essential nexus and rough proportionality requirements enshrined in the Nollan and Dolan cases. The narrow ruling reflects the sound principle that, when dealing with constitutional questions, a court shouldn’t address hypotheticals or other issues not in direct contention among the parties. Nonetheless, the majority felt compelled to state that it would not address “whether a permit condition imposed on a class of properties must be tailored with the same degree of specificity as a permit condition that targets a particular development,” which seems to leave open the possibility that the answer might be “no.” Justice Gorsuch, in his concurrence, was astonished by this statement, wondering how a court which had just endorsed the universal applicability of the takings clause could stumble into another arbitrary distinction with no basis in common sense or constitutional law. The court’s concern was not a jurisprudential one, but apparently a policy one: in another concurrence, Justices Kavanaugh, Kagan and Jackson note that “[i]mportantly, therefore, today’s decision does not address or prohibit the common government practice of imposing permit conditions, such as impact fees, on new developments . . . .” The justices’ impression that applying the current Nollan/Dolan formula to impact fees would or even could “prohibit” them is unfounded. As Emily Hamilton and I wrote […]

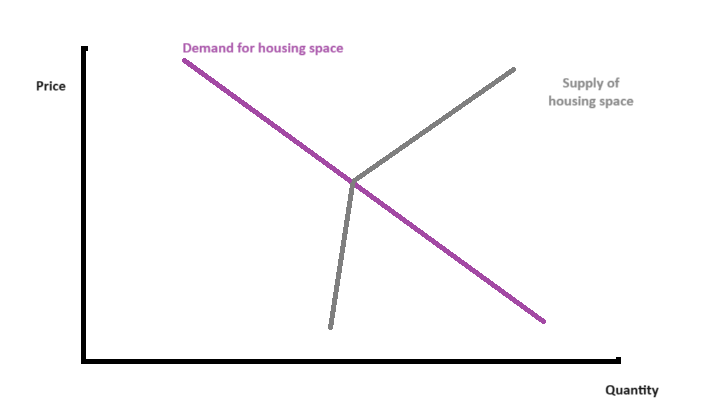

Should YIMBYs support or oppose greenfield growth? Two basic values animate most YIMBYs: housing affordability and urbanism. Sprawl puts those values into tension. Let’s take as a given that sprawl is “bad” urbanism, mediocre at best. Realistically, it’s rarely going to be transit-oriented, highly walkable, or architecturally profound. So the question is whether outward, greenfield growth is necessary to achieve affordability. And the answer from urban economics is yes. You can’t get far in making a city affordable without letting it grow outward. Model 1: All hands on deck Let’s start with a nonspatial model where people demand housing space and it’s provided by both existing and new housing. Existing housing doesn’t easily disappear, so the supply curve is kinked. A citywide supply curve is the sum of a million little property-level supply curves. We can split it into two groups: infill and greenfield, which we add horizontally. If demand rises to the new purple line, you can see that the equilibrium point where both infill & greenfield are active is at a lower price & higher quantity than the infill-only line. The only way to get some infill growth to replace some greenfield growth, in this model, is to raise the overall price level. And even then, the replacement is less than 1-for-1. Of course, this is just a core YIMBY idea reversed! In most U.S. cities, greenfield growth has been allowed and infill growth sharply constrained, so that prices are higher, total growth is lower, and greenfield growth is higher than if infill were also allowed. At the most basic level, greenfield growth is simply one of the ways to meet demand. With fewer pumps working, you’ll drain less of the flood. Model 2: Paying for what you demolish Now let’s look at a spatial model where people […]

In December, I was asked to testify at a House Subcommittee on Housing and Insurance hearing on government barriers to housing construction and affordability. I provided examples of reforms to land regulations that have facilitated increased housing supply, particularly relatively low-cost types of housing, including multifamily, small-lot single-family, and accessory dwelling units. Following the hearing, I received a good question from Congresswoman Sylvia Garcia. She points out that, as in the country as a whole, the share of cost burdened renters has increased in recent years in Houston, in spite of land use liberalization. She asked what local policymakers could do to improve affordability for low-income residents. When market-oriented housing researchers point to Houston’s relatively light-touch land use regulations as a model for other U.S. localities to learn from, its declining affordability may cause skepticism. Houston, however, has fared better than many other cities in housing affordability for both renters and homebuyers. While Houston is the only major U.S. city without use zoning, it does have land use regulations that appear in zoning ordinances elsewhere, including minimum lot size, setback, and parking requirements. These rules drive up the minimum cost of building housing in Houston. However, Houston has been a nationwide leader in reforming these exclusionary rules over the past 25 years. Houston policymakers have enacted rule changes to enable small-lot development and, in parts of the city, they have eliminated parking requirements. In part as a result, Houston’s affordability is impressive compared to peer regions. As the chart below shows, Houston has the lowest share of cost-burdened renter households among comparable Sun Belt markets for households earning 81% to 100% of the area median income. Only San Antonio and Austin have lower rates of rent burden among households earning 51% to 80% of the area median income. At the […]

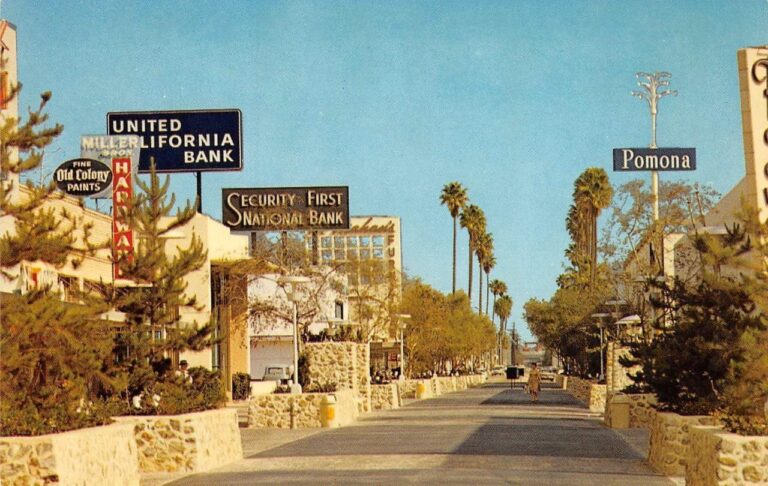

Urbanists love to celebrate, and replicate great urban spaces – and sometimes can’t understand why governments don’t: But what’s important to recall – especially for those of us under, uh, 41 – is that pedestrianized streets aren’t a new concept coming into style, they’re an old one that’s been in a three-decade decline. Samantha Matuke, Stephan Schmidt, and Wenzheng Li tracked the rise and decline of the pedestrian mall up to the onset of the pandemic. Even in the urbanizing 2000s and 2010s, 14 pedestrian malls were “demalled” against 4 streets that were pedestrianized: In a 1977 handbook promoting pedestrianization, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo admit that some of the earliest “successes” had already failed: In Pomona, California, the first year [1962] the mall received nationwide press coverage as a successful model of urban revitalization; there was a 40 percent increase in sales. But the mall was slowly abandoned by its patrons, and now, after fifteen years of operation, it is almost totally deserted. A Handbook for Pedestrian Action, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo, p. 25 One obvious reason for the failure of many other pedestrianized streets is that they were too little, too late. The pedestrian mall was one of several strategies against the overwhelming ebb tide of retail from downtowns in the postwar era. They weren’t seen as alternatives to driving, but destinations for drivers, who could park in the new, convenient downtown lots that replaced dangerous, defunct factories. A minority of the postwar-era malls survived. The predictors of survival are sort of obvious in hindsight: tourism, sunny weather, and lots of college students, among other things. Some of the streets which were “malled” and “demalled” have rebounded nicely in the 2000s. The slideshow below shows Sioux Falls’ Phillips Avenue in 1905, 1934, c. 1975, and 2015. The […]

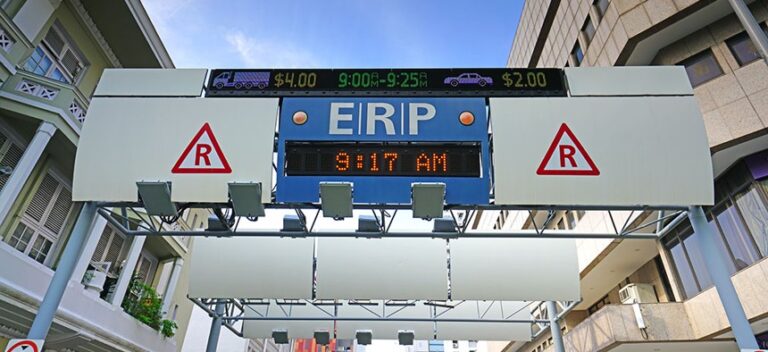

In a series of recent posts, Tyler Cowen has taken the view that congestion prices in major downtowns are a bad idea. This is what one might expect of a typical New Jerseyan, but not a typical economist. The writing in these posts is a bit squirrelly (or is it Straussian?), but as best I can make out, Tyler is deviating from the mainline economic views of externalities and prices by arguing a few points: Urban serendipity and growth are high-value externalities quite distinct from the usual efficiencies of combining large amounts of capital and labor in downtown office towers. Occasional visitors to the city find very high value there (presumably via a long-right-tail distribution) including by creating demand for new goods Congestion pricing will (a) decrease the number of people in the city, (b) particularly high-value visitors. He also makes some specific critiques of the mechanism design of the proposed NYC congestion charge. It’s worth getting that right, but let’s leave the technicalities aside here. Tyler’s points – as I’ve summarized (or mangled) them – seem like a mix of reasonable and wrong, although in several cases difficult if not impossible falsify. I’ll tackle these points in a completely irresponsible order. 2. Distinguished visitors On the second point: Diminishing marginal returns is enough to give Tyler’s argument the benefit of the doubt. The first visit to a symphony or subway likely has a bigger inspirational impact than the seventh or seven-hundredth. And outsiders may bring insights to the city in an Eli-Whitney-and-the-cotton-gin way. But for consuming new goods? Perhaps visitors’ demand is enough to sustain new imitations of low-end consumer goods (like a McDonalds in Chennai, if there is one). But for narratives of urban creativity, I prefer Malcolm Gladwell’s account of Airwalk shoes or Peter Thiel’s identification of […]

The state of Massachusetts lets municipal governments choose how strictly they regulate energy efficiency in buildings. Fifty-two of the state’s municipalities use the base building code, whereas 299, including Boston, have opted into the stricter “stretch” energy code. In addition to these two, the state recently rolled out an even stricter “specialized” stretch code in the interest of getting to net-zero carbon emissions faster. Cities could opt in to the specialized code as of last December; several municipalities have already opted in, and Boston may do so soon. The new code is technically the Municipal Opt-In Specialized Stretch Energy Code, and I considered referring to it hereinafter as MOISSEC, which is cute because it sounds like a wine, but I ended up deciding that the least confusing option is to follow official documents in referring to the new option as the specialized code, and refer to what is existing law in most of the state as the stretch code. Given that Massachusetts has some of the most expensive housing in the country, it’s reasonable to worry about the impact of any housing regulations on affordability, even when they serve an important objective. Massachusetts had the third highest cost of new housing of all states in 2021, and has unusually low housing supply, even among expensive coastal states. Research from the Boston Foundation details the extent of the problem: Greater Boston has lower vacancy rates than even Los Angeles or New York, homes spend less time on the market in Boston, and Boston is not on track to meet its housing production goals, though construction has increased somewhat in recent years. A new report released Tuesday by the MIT Center for Real Estate, the Home Builders and Remodelers Association of Massachusetts (HBRAMA), and Wentworth Institute of Technology (WIT) projects the impact […]

“Renting in Providence puts city councilors in precarious situations.” That was the Providence Journal’s leading headline a few days ago, as the legislature waited for Governor Daniel McKee to sign a pile of housing-related bills (Update: He signed them all). Rhode Island doesn’t have a superstar city to garner headlines, but it’s housing costs have mounted as growth has crawled to a standstill. But unlike in Montana and Washington, Rhode Island’s were largely procedural, aiming to lubricate the the gears of its existing institutions rather than directly preempting local regulations. House Speaker Joseph Shekarchi (D-Warwick), who championed the reforms, clearly drew on his professional expertise as a zoning attorney to identify areas for procedural streamlining. Specific and objective Six bills transmitted to the governor cover the general rules affecting most Rhode Island zoning procedures: S 1032 makes it easier to acquire discretionary development permission. Municipalities cannot enforce regulations that make it near-impossible to build on legacy lots that do not meet current regulatory standards. Municipalities can more quickly issue variances and modifications. (Rhode Island draws a unique distinction between minor and substantial variances, labeling the former “modifications” and subjecting them to a simpler process. A substantial variance must go before a board for approval; a modification can be approved administratively unless a neighbor objects. Municipalities must issue “specific and objective” criteria for “special use permits”, otherwise those use are automatically allowed as of right. That phrase – specific and objective – shows up again and again in Speaker Shekarchi’s bills. S 1033 requires that zoning be updated to match a municipality’s own Comprehensive Plan within 18 months of a new plan’s adoption. It also requires an annually updated “strategic plan” for each municipality, although the content and legal force of the strategic plans are unclear to me. S 1034 broadly […]

The Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley has released a policy brief summarizing the effect on housing production of the bewildering array of new housing laws California has enacted since 2016. A preliminary analysis of market effects of the new laws, accompanied by findings from interviews with California-based planners and land use lawyers, points toward the effectiveness of simple and direct legislation requiring localities to give ministerial approval to small-scale projects. For other laws, including those prescribing more complex formulas regarding affordability criteria for larger developments, it remains too early to gauge how housing production will respond. Of the legislation that has been enacted to date, California’s accessory dwelling unit laws (beginning with SB 1069 in 2016), according to those interviewed by the Terner Center, have been responsible for the astonishing twenty-fold increase in ADU permits documented from 2016 to 2021. Legislation enacted in 2021 requiring ministerial approval for duplexes and lot splits (SB 9), estimated by the Center to allow for up to 700,000 new units, has not yet been widely used, partly due to localities’ use of other restrictive zoning regulations such as mandatory setbacks to impede use of the law. Further strengthening of this law, in the same manner that the ADU law was fortified through 2019 revisions, may be necessary to unlock its full potential for new home construction. Other new laws are in the early stages of demonstrating their effectiveness. The imposition of stricter requirements on localities’ Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) process through legislation enacted in 2017 and 2018 has resulted in dramatic increases in zoning capacity targets for the next eight-year period set by the Housing Element Law (of which the RHNA is a part). For Southern California and the Bay Area, total housing allocation has increased from […]