Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The best book on zoning and NIMBYism you’ve never read might well be The Housing Bias by Paul Boudreaux. The author is a law professor, but you’d be forgiven for thinking he’s a journalist. His writing is engaging – and occasionally funny – and he does what is unthinkable for many scholars: drives to various places to interview people who are engaged in the (legal) drama of what we now call “the housing crisis.” Boudreaux had the misfortune of being ahead of his time. The housing market was so soft in 2011 that his book landed with nary a sound. A quick web search turned up no book reviews besides the publisher’s blurbs. The book (and you’ll be forgiven if you stop reading right here) will set you back. That’s unfortunate. Just a few years later, the book would have connected with passions shared by the rapidly growing YIMBY movement and a publisher would have marketed it to the masses. Boudreaux’s thesis is that “the laws that govern our use of land are biased in favor of one specific group of Americans—affluent, home-owning families—who least need the government’s help.” He keeps his ideological cards close to the vest. But that’s the point: one need not lean left or right to want to stop using the power of the state to comfort the comfortable and afflict the afflicted. The first chapter is the most important, because it lays out the foundation for all that local governments do, good and bad, in land use: the police power. He’s writing from Manassas, Virginia, where “restaurants with Aztec pyramids on them” telegraph the large Hispanic immigrant community. A vocal minority opposed this local immigration, and pressured local governments to stop it. Of course, the city doesn’t issue passports, but the police power allows local […]

Christian Hilber and Andreas Mense argue that the price to rent ratio only increases with a demand shock where supply is sufficiently constrained

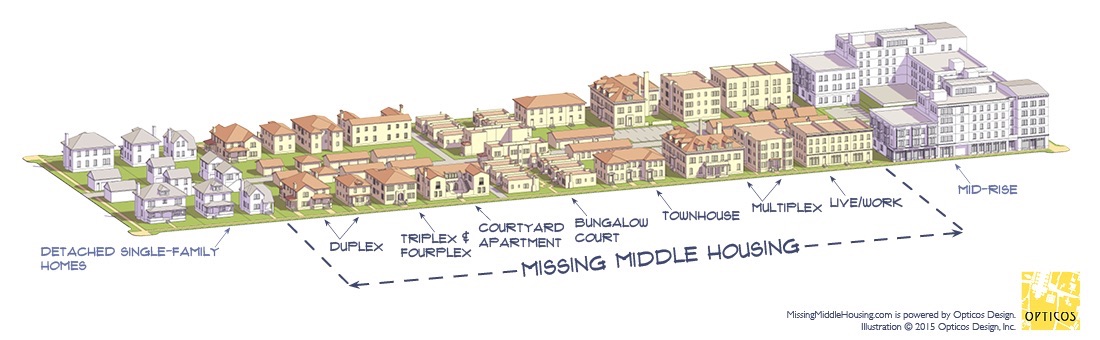

After over a century, Berkeley, California may be about to legalize missing middle housing – and it’s not alone. Bids to re-legalize gradual densification in the form of duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and the like have begun to pick up steam over the last several years. In 2019, Oregon legalized these housing types statewide while Minneapolis did the same at the city level. In 2020, Virginia and Maryland both tried to pass similar legislation, though they ultimately failed. This year, though, Montana and California may pick up the torch with their own state bills (even while the cities of Sacramento and South San Francisco consider liberalizing unilaterally alongside Berkeley). Allowing gradual densification is an absolutely necessary step towards general affordability. Supply, demand, and price form an iron triangle–the more responsive we can make supply to demand, the less price will spike to make up the difference.* What I really want to focus on here, though, is less about policy and more about political economy. I believe allowing medium-intensity residential development could make additional reforms easier to achieve and change views around development going into the future. We Love What We Know More often than not, I think a generalized status quo bias explains a lot of NIMBYism. Homeowners are most comfortable with their neighborhoods as they are now and are accustomed to the idea that they have the right to veto any substantial changes. Legalizing forms of incrementally more intense development could re-anchor homeowners on gradual change and development as the norm. The first part of the story is about generational turnover. If the individuals buying homes today–and the cohorts that follow–are exposed to gradually densifying neighborhoods in their day-to-day, they’ll anchor on that as what’s normal and therefore acceptable. Moreover, if we’re debating whether to rezone an area for mid-rise […]

A recent paper by UCLA researchers discusses 2019-20 literature on the relationship between new construction and rents. The article discusses five papers; four of them found that new housing consistently lowers rents in nearby buildings. For example, Kate Pennington wrote a paper on the relationship between new construction and housing costs in San Francisco. What is unique about this paper is that while other papers focus on a broad sample of new construction, Pennington focuses on one subset of the market: “new construction caused by serious building fires.” Why? Because most new construction is in high-demand areas. Any study that focuses on such construction will be more likely to conclude that the new construction is related to high rents, when in fact the real cause of increased rents is increased demand for certain neighborhoods. Pennington found that rents actually decreased within 500 meters of new buildings- by 2.3 percent, compared to similar blocks without new buildings. Pennington also found 17.1 percent less displacement (which she defines as moves to poorer zipcodes) near the new buildings, and found that landlords were less likely to evict rent-controlled tenants. One paper was a partial exception to the pro-supply trend of recent scholarship: a paper by Anthony Damiano and Chris Frenier found that new buildings in Minneapolis lowered rents for most nearby buildings, but increased rents for the cheapest buildings. But the UCLA researches point out that “Damiano and Frenier do not adjust the rents in their study for inflation, which is an unusual decision, and one that makes the rent increases they report look much larger than they actually were.” Adjusted for inflation, rents near new buildings declined by 7 percent overall, and increased by only 0.2 percent for the cheapest buildings. One point that the UCLA researches do not mention: although the […]

Night City: the cyberpunk themed sandbox of William Gibson’s darkest tech-themed dreams, and despite the host of game-breaking glitches, home to all the anti-urban nightmares that the genre helped spawn. In this episode of Pop Culture Urbanism, I dig deep into the cyberpunk genre, the era that spawned and popularized it, and subsequent “unseen” opportunity cost of de-urbanization that continues to haunt us to this day. Be sure to follow future episodes by subscribing to the Pacific Legal Foundation on YouTube! We have a lot of content in the hopper that you won’t want to miss. Directed by Calvin Tran and produced by our friends at the Pacific Legal Foundation.

A major barrier to the market urbanist’s ability to make the case for building more housing is the question of aesthetics. When you refer to density in cities, it’s easy to picture large brutalist towers and the slum-like conditions that can be seen in much of the developing world. Of course, this isn’t what we advocate, but it is a problem we have to repeatedly address. Homeowners, whether we like it or not, are a powerful voter group and they want to live in areas that look nice. Fortunately, the British Government has found the golden mean of housing plans by accepting the results of the Building Better, Building Beautifully Commission.. The key takeaway of this report is street-voting. This represents an excellent middle ground between the seemingly opposite need for housing to be popular, and the need for housing to be plentiful. The current system used in England fails to provide a fair way of measuring public views on plans. This works by assessing the views of nearby residents through a consultation. This allows any resident to attend, or write in, laying out their views on the plan. It may sound democratic, but local consultations are notoriously unrepresentative of a community. Those who take part are overwhelmingly middle-class, property-owning white people who stand to benefit from a housing shortage. Rather than taking into account the views of the local area, this method merely measures the views of those who would be economically burdened by addressing the crisis. The city as a commons What we’re left with is what social scientists would call the tragedy of the commons. This is where you have a common-pool resource where individual use of that resource depletes the stock for other parties. Cities can also be understood to be “the commons” in that they […]

Welcome to Twin Peaks: home of black coffee, cherry pie, murder, intrigue, and the endangered pine weasel. To kick off season two of Pop Culture Urbanism, I dive into David Lynch’s eccentric nightmare/daytime soap opera world to examine the age old trope of the bad guy developer and how they manipulate environmental regulation to their financial advantage. Video goes live at noon PT 1/28! Be sure to follow future episodes by subscribing to the Pacific Legal Foundation on YouTube! We have a lot of content in the hopper that you won’t want to miss. For the New Urbs article that inspired this video, click here.

Current events being what they are, I’m happy to be writing about something positive. Once again, we’re getting an ambitious housing reform package in the California legislature. The various bills focus on removing obstacles to new housing and are a sign of the growing momentum Yimby activists have built up over the last few years. The permitting process for new housing in California is the bureaucratic equivalent of American Ninja Warrior. Localities use restrictive zoning and discretionary approvals to block new construction. When faced with state level oversight, California cities have historically leaned on bad faith requirements to ensure theoretically permitted and approved housing remains commercially infeasible. And as if that weren’t enough, “concerned citizens” can use the ever popular CEQA lawsuit to kill projects themselves (independent of direct involvements from electeds). This year’s housing package helps reduce the difficulty of getting a project through the gauntlet. Still an obstacle course, but with a few less water hazards and a slightly shorter warped wall. Still suboptimal, but directionally correct in a very big way. There are several pro-supply bills in the package, but two are especially worth calling out. SB 6 allows for residential development in areas currently zoned for commercial office or retail space. The bill would also create opportunities for streamlined approval if some portion of a proposed project site has been vacant. This last bit seems to be intended to encourage redevelopment of dead malls and similar retail heavy areas that could be better put to use as housing. SB 9 allows for duplexes and lot splits in single family zones by right. This type of missing middle housing could – at least in certain parts of California – be new housing that’s less expensive then existing stock; that’s a great outcome from a policy perspective, but […]

Someone just posted a video on Youtube using Houston, Texas as an argument in favor of zoning. The logic of the video is: Houston is horrible; Houston has no zoning; therefore every city should have conventional zoning. This video and its logic are impressively wrong, for several reasons. First, I’ve been to Houston and most of what I saw looks nothing like the video – there are plenty of blocks dominated by houses and the occasional condo. Second, most of the photos in the video could have easily happened in a zoned city, because one block in a neighborhood could be residential and the next block could be commercial, so the commercial or industrial activities can be easily viewable from the residential areas (not that anything is wrong with that). Third, most other automobile-dependent cities aren’t any prettier than Houston; a strip mall in Houston doesn’t look any worse than a strip mall in Atlanta. Fourth, it completely overlooks the negative side effects of zoning as it is practiced in most of the United States (many of which have been addressed more than once on this site). Typically, residential zones are so enormous that most of their residents cannot walk to a store or office. Moreover, density limits everywhere limit the supply of modest housing, thus creating housing shortages and homelessness. Finally, Houston’s negative characteristics are partially a result of government spending and regulation; as I have written elsewhere, that city has historically had a wide variety of anti-walkability policies, so it is far more regulated than the video suggests.

One common argument against new housing is that the laws of supply and demand simply don’t apply to dense cities like New York, San Francisco ands Hong Kong, because new housing or upzoning might raise land prices.* After all (some people argue) Hong Kong is really dense and really expensive, so doesn’t that prove that dense places are always expensive? A recent paper by three Hong Kong scholars is quite relevant. They point out that housing supply in Hong Kong has grown sluggishly in recent years. They write that in the late 1980s, housing supply grew by 5 percent per year. But since 2009, housing supply has grown at a glacial pace. Between 2009 and 2015, housing supply typically grew by around 0.5 percent per year; in the past couple of years, it has grown by between 1 and 1.5 percent per year. The authors note that these numbers actually overstate supply growth, because they do not include housing that has been demolished. Not surprisingly, housing prices have grown more in recent years. In the 1980s, housing costs increased by roughly 1 percent per year; in the past decade, costs have risen by as much as 3 percent per year. (Figure 4d). Thus, Hong Kong data actually supports the view of many American scholars that housing prices tend to be highest in places where housing supply fails to grow. Why is supply stagnant? The authors point out that in Hong Kong, as in some U.S. cities, government limits housing density through floor area ratio regulations. And because Hong Kong land is government-owned, the local government can restrict housing supply by refusing to sell vacant land. Because high land costs mean more revenue for the government, government has an incentive to sell land slowly in order to keep land prices high. […]