Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

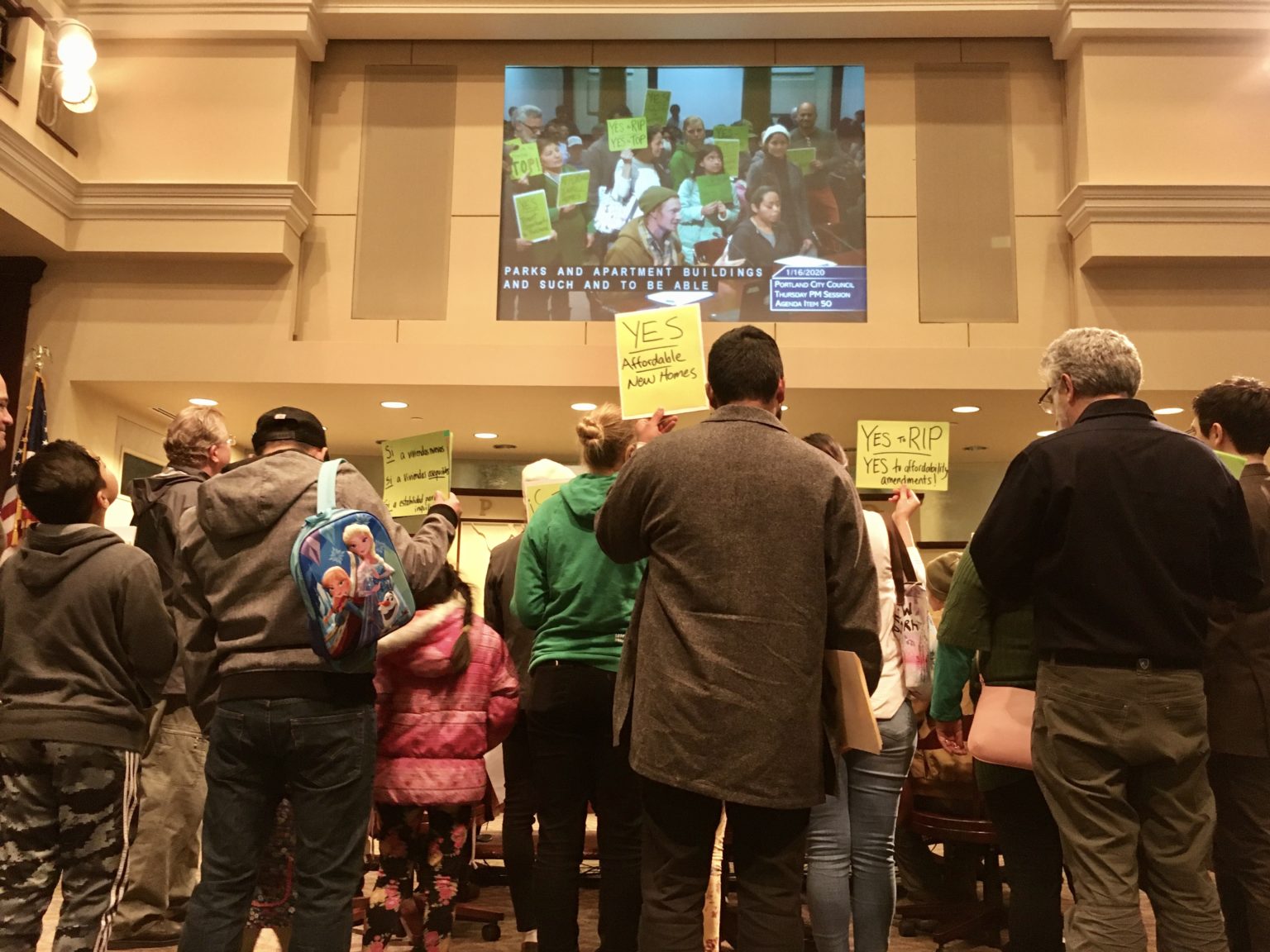

Case studies from several authors help explain the gritty politics of "Yes." The list includes three classics and will be expanded with reader submissions.

I am currently reading A Fortress in Brooklyn, a (mostly) fine book about the relationship between Williamsburg’s Satmar Hasidim and real estate policy. One chapter discusses Satmar opposition to bike lanes in their neighborhood, and suggests that one cause of this opposition might be that “the Hasidic community in Williamsburg developed a pervasive and entrenched culture of driving automobiles.” In an otherwise heavily footnoted book, the authors supply no footnotes to support this claim. Is it true? Let’s look at the 2019 Census data. There are three Census tracts that include the core of Lee Avenue (the main street of Hasidic Williamsburg): tracts 531, 533 and 535 in Brooklyn. According to the American Community Survey (ACS), the percentage of occupied housing units without automobiles ranged from 63 percent (tract 531) to 85 percent (tract 535). Admittedly, ACS data for anything smaller than a city is subject to a large margin of error; however, it is pretty common for car ownership to be low in neighborhoods that are (like Hasidic Williamsburg) close to Manhattan, have a 55 percent poverty rate, and have over 80,000 people per square mile. Another heavily Hasidic area, Borough Park, is further from Manhattan, more affluent, and less dense. (The primary zip code of Borough Park, 11219, has a 32 percent poverty rate, and has only 60,000 people per square mile). Yet even in the Boro Park zip code, most households lack a vehicle. ACS commuting data is consistent with these figures. In all three Census tracts, fewer than 1/4 of workers drove or carpooled to work. Public transit use was roughly comparable, because the majority of workers worked in the neighborhood and walked to work. To me the most interesting question is, why did these otherwise careful authors get it wrong? I have two theories. First, […]

In July, I showed that an otherwise careful group of researchers at the Othering and Belonging Institute were using a measure of statistical racial segregation that confounds diversity with segregation. Briefly, regions with more variety in the racial makeup of their neighborhoods will show up as statistically “segregated.” Regions where all neighborhoods are pretty similar will show up as statistically “integrated.” To their credit, the study authors corresponded with me at length and adjusted their Technical Appendix to emphasize limitations that I had pointed out. Today, Mark Zandi, Dante DeAntonio, Kwame Donaldson, and Matt Colyar of Moody’s Analytics released a much less careful study purporting to show the “macroeconomic benefits of racial integration.” But if one were to make the mistake of taking their study at all seriously it would lead one to the opposite conclusion: mostly-white counties do better economically. They discovered white privilege and mislabeled it “integration.” (When economists talk about “segregation” statistically, they mean differences in racial proportions across neighborhoods. This is not the same as the de jure segregation regime imposed in the American South. It’s not even the de facto segregation that persists in some neighborhoods today.) The easiest way to see Zandi et al’s mistake is to work backwards from the table of county results they (helpfully) published. The most integrated county in America, in their analysis, is Kennebec County, Maine. It’s 94.6% white. The rest of the most-integrated counties are similarly pallid – with the exception of Webb County, Texas, which is 95% Hispanic. In each of these counties, integration is a mathematical product of the lack of diversity. With hardly any minorities, hardly any neighborhood can diverge from the dominant group. These extreme counties aren’t an accident. Whereas most researchers treat metropolitan areas together, Zandi’s team worked with counties. Several of their […]

A few weeks ago the Times reported that Lloyds Banking Group had purchased 45 new homes to let in Peterborough. This is part of a plan for Lloyds to own 50,000 homes by 2031. Given the median home in the City is now worth over 7 times the annual earnings of the typical resident, it is understandable why people would be upset. Indeed, why should a huge corporation be able to buy up all the properties in the City, when its own residents can’t afford to buy a new home there? However, this outrage is misdirected. Lloyds buying a few thousand homes over a decade will do nothing compared to the astronomical effect that NIMBYism and our planning system has had on house prices. The reason for this lies in a piece of legislation called the Town and Country Planning Act. This law abolished the automatic right to develop regulatory compliant housing, and added an additional stage of planning permission. As a result, it became mandatory for one to require state permission to build on one’s own land. Over the years this system has morphed into an almost quasi-right to block others’ construction giving residents the ability to stop others from moving into their area. This chiefly benefits homeowners – the people who engage the most in the planning system – since new houses will slow down the speed their own home’s value increases. The effect is that almost no houses get built. For example, in London during the 2010s we built around 25,000 houses per year; in the 1930s before the Planning Act was introduced that number was 61,500. Sadly housing just behaves like any other scarce asset. When there’s a shortage the sellers have more bargaining power and consumers are forced to pay more to buy the goods. […]

One common explanation for high rents is something called “financialization.” Literally, this term of course makes no sense: any form of investment, good or bad, involves finances. But I think that the most common non-incoherent use of the term is something like this: rich people and corporations have decided that real estate is a good investment, and are buying it, thus driving up demand and making it more costly. But if this is true, to blame financialization for high rents and sale prices is to confuse cause and effect. If real estate prices weren’t going up, it wouldn’t make sense to buy buildings as investment. Thus, high housing costs cause financialization, not vice versa. In fact, if government did not restrict housing supply through zoning, financialization would be a force for good. Why? Because instead of buying existing buildings, people with money might be more willing to build new buildings for people to live in- which in turn might hold housing costs down. PS I am running for Borough President of Manhattan, and am gradually creating a Youtube page that addresses anti-housing arguments in more detail.

Hayek says that planning is the road to serfdom. Holland may be the most thoroughly planned country on earth - and it's delightful. How does a market urbanist respond to excellent planning?

In the standard urban growth model, a circular city lies in a featureless agricultural plain. When the price of land at the edge of the city rises above the value of agricultural land, “land conversion” occurs. In the real world, we’re more likely to call it “development” and it is, of course, a lot more complicated. Simplification is valuable and gives us more general insights. But is greenfield development complicated in ways that are interesting and might change the results of urban economic models? Or that might change the ways we think or talk about development policy? Witold Rybczynski’s 2007 book Last Harvest helps answer these questions. It tracks a specific cornfield in Londonderry, Pennsylvania, from the retirement of the last farmer to the moving boxes of the first resident. With its zoomed-in lens, Last Harvest answers (or at least raises) lots of questions that are interesting but not especially important in the grand scheme: Why do expensive homes mix some top-line finishes with cheap, plasticky ones? Why do anti-development communities permit any subdivisions at all? What is ‘community sewerage,’ and how does it work? Exactly who thinks it’s attractive to have brick and vinyl cladding on the same house? What’s it like to buy a house from a national homebuilder? Does Chester County really produce forty percent of America’s mushrooms? The Stack Rybczynski does not use this term, but what he describes is part of what I call the “stack” of housing supply. One of the central facts of development is that it relies on a very long chain of industries and professions, each of which relies on every other part of the stack doing its job. If one part is left undone, nobody gets paid: ‘Without a water contract, we can’t get a permit for the water mains, […]

Headlines last month proclaimed that “Cities Have Grown More Diverse, And More Segregated, Since the 90s.” The headlines originate in the key findings of a new, detailed study from the Othering and Belonging Institute (OBI) at UC Berkeley. The study leans heavily on a relatively new metric – the Divergence Index – which has impressed many researchers (myself included) with its versatility. But now that we have seen the Divergence Index in action, its versatility clearly comes at a cost: the Divergence Index conflates what we would intuitively call diversity with “segregation.” As a result, more-diverse metro areas are usually ranked as more segregated by the Divergence Index. And as America became far more diverse over the past 30 years, it is logical that the Divergence Index would rise in most metro areas. Why is it so hard to measure segregation? Racial segregation is easy to see. You walk down the street and almost everybody in one neighborhood looks different than you and almost everybody in another neighborhood looks the same as you. The human eye and ear can also distinguish categories that are meaningful in some contexts but not others. Everybody but me in the café where I watched European soccer last week appeared to be not only Black but specifically Ethiopian. Was that café integrated or segregated? I certainly felt welcome as I bantered at the bar with an Ethiopian-American tennis instructor. But statistically, the café was far more Black and vastly more Ethiopian than the D.C. region as a whole. In this context, “segregation” refers to places where one group is overrepresented – like the café – not to the legal regime that imposed second-class citizenship and pervaded every aspect of life for black Americans. Given the word’s loaded history, it would have been wiser for social […]

Over the years, I’ve heard a wide variety of arguments against new housing. One of them is the “mysterious foreign investor” argument. According to this theory, new urban housing will all be bought up by billionaire foreign investors, who will purchase the property and never rent it out, thus preventing the new housing from increasing supply. (I have rebutted the argument here).* A variation of the argument is that because some high-end housing is vacant, supply is therefore adequate to meet demand. (I have addressed this idea here). Another argument is that housing markets are segmented: that if you increase the supply at the top of the market, it will not help anyone who is not already at the top of the market. It seems to me that these arguments contradict each other: the first argument is based on the idea that high-end housing does affect the market as a whole (or would if rich people stopped using apartments as second homes); the second is based on the idea that high-end housing doesn’t affect the rest of the market at all. *In addition, I have recently published a much longer article in the New Mexico Law Review, discussing the pros and cons of high-end condos.

There was an interesting article in the New York Times magazine this week on the rise of extended stay hotels, which specialize in renting to a group within the working poor- people who have the cash for weekly rent, but cannot easily rent traditional apartments due to their poor credit ratings. This seems like a public necessity – but even here the long arm of big government seeks to smash affordability. The article notes that Columbus, Ohio “passed an ordinance that subjects them to many of the same regulations as apartments” because “The hotels had an unfair competitive advantage.” In other words, the city is basically rewarding landlords for turning out bad-credit tenants, and punishing the hotels who seek to house them.