Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

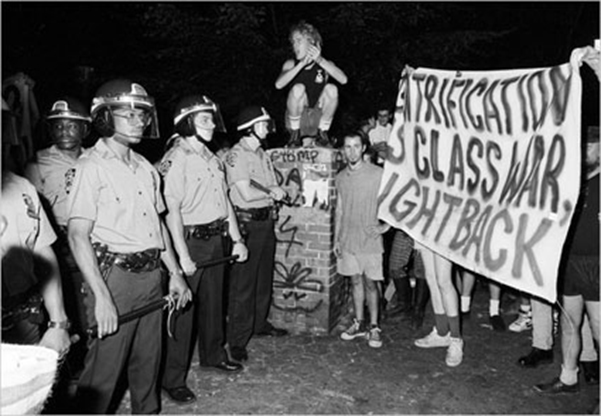

Gentrification is the result of powerful economic forces. Those who misunderstand the nature of the economic forces at play, risk misdirecting those forces. Misdirection can exasperate city-wide displacement. Before discussing solutions to fighting gentrification, it is important to accept that gentrification is one symptom of a larger problem. Anti-capitalists often portray gentrification as class war. Often, they paint the archetypal greedy developer as the culprit. As asserted in jacobin magazine: Gentrification has always been a top-down affair, not a spontaneous hipster influx, orchestrated by the real estate developers and investors who pull the strings of city policy, with individual home-buyers deployed in mopping up operations. Is Gentrification a Class War? In a way, yes. But the typical class analysis mistakes the symptom for the cause. The finger gets pointed at the wrong rich people. There is no grand conspiracy concocted by real estate developers, though it’s not surprising it seems that way. Real estate developers would be happy to build in already expensive neighborhoods. Here, demand is stable and predictable. They don’t for a simple reason: they are not allowed to. Take Chicago’s Lincoln Park for example. Daniel Hertz points out that the number of housing units in Lincoln Park actually decreased 4.1% since 2000. The neighborhood hasn’t allowed a single unit of affordable housing to be developed in 35 years. The affluent residents of Lincoln Park like their neighborhood the way it is, and have the political clout to keep it that way. Given that development projects are blocked in upper class neighborhoods, developers seek out alternatives. Here’s where “pulling the strings” is a viable strategy for developers. Politicians are far more willing to upzone working class neighborhoods. These communities are far less influential and have far fewer resources with which to fight back. Rich, entitled, white areas get down-zoned. Less-affluent, disempowered, minority […]

Want to live in San Francisco? No problem, that’ll be $3,000 (a month)–but only if you act fast. In the last two years, the the cost of housing in San Francisco has increased 47% and shows no signs of stopping. Longtime residents find themselves priced out of town, the most vulnerable of whom end up as far away as Stockton. Some blame techie transplants. After all, every new arrival drives up the rent that much more. And many tech workers command wages that are well above the non-tech average. But labelling the problem a zero sum class struggle is both inaccurate and unproductive. The real problem is an emasculated housing market unable to absorb the new arrivals without shedding older residents. The only solution is to take supply off its leash and finally let it chase after demand. Strangling Supply From 2010 to 2013, San Francisco’s population increased by 32,000 residents. For the same period of time, the city’s housing stock increased by roughly 4,500 units. Why isn’t growth in housing keeping pace with growth in population? It’s not allowed to. San Francisco uses what’s known as discretionary permitting. Even if a project meets all the relevant land use regulations, the Permitting Department can mandate modifications “in the public interest”. There’s also a six month review process during which neighbors can contest the permit based on an entitlement or environmental concern. Neighbors can also file a CEQA lawsuit in state court or even put a project on the ballot for an up or down vote. This process is heavily weighted against new construction. It limits how quickly the housing stock can grow. And as a result, when demand skyrockets so do prices. To remedy this, San Francisco should move from discretionary to as-of-right permitting. In an as-of-right system, it’s much […]

I noticed an interestingly ironic thing today. The usual argument for the necessity of use-based zoning is that it protects homeowners in residential area from uses that would potentially create negative externalities – ie: smelting factory, garbage dump, or Sriracha factory. Urban Economics teaches us that such an event happening is highly unlikely in today’s marketplace. (nevermind the fact that nuisance laws should resolve these disputes) The business owner who is looking for a site for a stinky business would be foolish to look in a residential area where land costs are significantly higher. However, as Aaron Renn pointed out in the comments of my last post on Planned Manufacturing Districts, the inverse of this is happening in many cities as residential uses begin to outbid other uses in industrial areas: I think part of the rationale in this is that once you allow residential into a manufacturing zone, the new residents will start issuing loud complaints about the byproducts of manufacturing: noise, smells, etc. I know owners of businesses in Chicago who have experienced just that. They’ve been there for decades but now are getting complaints from people who live in residential buildings that didn’t even exist when the manufacturer located there. This puts those businesses under a lot of pressure to leave as officials will almost always side with residents who vote rather than businesses who don’t get to. It’s clear this is a more relevant defense of use-based zoning than the one we usually hear. Of course, I’d argue that segregating uses through zoning isn’t a just way to resolve these disputes, and my last post discusses some of the detrimental consequences for cities. It seems ironic, because it inverts the usual argument in-favor of zoning. Residents are choosing to move near established industrial firms, and PMDs are a tool […]

They are called different things in different cities, but they are similar in form and intent among the cities where they are found. For simplicity’s sake, a Planned Manufacturing District (PMD), as they are called in Chicago, is an area of land, defined by zoning, that prohibits residential development and other specific uses with the intent of fostering manufacturing and blue-collar employment. Proponent of PMDs purport to be champions of the middle-class or blue-collar workers, but fail to consider the unintended consequences of prohibiting alternative uses on that land. At best, PMDs have little effect on changing land-use patterns where industrial is already the highest-and-best-use. At worst, they have the long-run potential to distort the land use market, drive up the costs of housing, and prevent vibrant neighborhoods from emerging. A Race to The Bottom Before getting into it further, it is important to examine the economic decisions industrial firms make in comparison to other uses. Earlier in the industrial revolution, industry was heavily reliant on access to resources. Manufacturing and related firms were very sensitive to location. The firms desired locations with easy access to ports, waterways, and later railways to transport raw materials coming in, and products going out. However, the advent of the Interstate Highway System and ubiquitously socialized transportation network have made logistical costs negligible compared to other costs. Where firms once competed for locations with access to logistical hubs and outbid other uses for land near waterways in cities, they now seek locations with the cheapest land where they can have a large, single-floor facility under one roof. This means sizable subsidies must be combined with the artificially cheap land to attract and retain industrial employers on constrained urban sites. Additionally, today’s economy has become much more talent-based rather than resource based, and patterns have shifted accordingly. In contrast to industrial, residential and office uses are […]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n-zESacteu4 Yesterday, Reason TV released a video comparing Houston with more heavily regulated East Coast cities, explaining that Houston’s relatively lax land use regulations contribute to its housing costs that are much lower than in other large cities. While the video paints an exaggerated picture of Houston as a free market paradise in spite of its codified sprawl, Todd Krainin makes some great points about Houston’s land use tolerance. For example, the city’s tin houses that save on construction and energy costs would be illegal in many cities that have tighter restrictions on building codes. In the video, the former mayor of Victoria, TX makes the great point that in spite of the absence of Euclidean Zoning in some Texas cities, residents don’t need to worry about heavy industry cropping up in their neighborhoods. “Economics dictates that you’re not going to put a rendering plant next to a residential subdivision,” he says. He’s referring to rent gradients that lead to land near amenities being priced at higher rates than land farther from amenities. Owners of low-value land uses don’t choose to pay high prices to be near these amenities. While there are occasionally legitimate nuisance cases in which housing and industrial uses impose externalities on each other because of their proximity, in a free market these cases would be very rare because it doesn’t make sense for industrial uses to take place on the land that people are willing to pay premium prices to live on. While city planners make the case for Euclidean zoning by saying that they are protecting residents from living near industry, zoning often results in the exact opposite outcome. Valuable property in cities including New York and San Francisco that is zoned industrial gets surrounded by residential neighborhoods over time as the city grows. Planners’ inability to keep codes up to date […]

Affordable housing policies have a long history of hurting the very people they are said to help. Past decades’ practices of building Corbusian public housing that concentrates low-income people in environments that support crime or pursuing “slum clearance” to eliminate housing deemed to be substandard have largely been abandoned by housing affordability advocates for the obvious harm that they cause stated beneficiaries. While rent control remains an important feature of the housing market in New York and San Francisco, even Bill de Blasio’s deputy mayor acknowledges the negative consequences of strong rent control policies. In the U.S. and abroad, politicians and pundits are beginning to vocalize the fact that maintaining and improving housing affordability requires housing supply to increase in response to demand increases. While support for older housing affordability policies has dissipated, the same isn’t true of inclusionary zoning. From New York to California, housing affordability advocates tout IZ as a cornerstone of successful housing policy. IZ has emerged as the affordable housing policy of choice because it has the benefit of supporting socioeconomic diversity, and its costs are opaque and dispersed over many people. However, IZ has several key downsides including these hidden costs and a failure to meaningfully address housing affordability for a significant number of people. Shaila Dewan of the New York Times captures the strangeness of IZ’s popularity: New York needs more than 300,000 units by 2030. By contrast, inclusionary zoning, a celebrated policy solution that requires developers to set aside units for working and low-income families, has created a measly 2,800 affordable apartments in New York since 2005. Montgomery County, a Maryland suburb of DC, has perhaps the most well-established IZ policy in the country. After 30 years, the program has produced about 13,000 units. Montgomery County is home to over one million people, 20 percent of whom have a household income of less than $43,000 annually. While this is an extraordinarily high income distribution relative to the rest of the country, this makes the […]

At Cato At Liberty, Randall O’Toole provides a list of recommendations for reversing Rust Belt urban decline in response to a study on the topic from the Lincoln Land Institute. He focuses on policies to improve public service provision and deregulation, but he also makes a surprising recommendation that declining cities should “reduce crime by doing things like changing the gridded city streets that planners love into cul de sacs so that criminals have fewer escape routes.” This recommendation is surprising because it would require significant tax payer resources, a critique O’Toole holds against those from the Lincoln Land Institute. Short of building large barricades, it’s inconceivable how a city with an existing grid of streets would even go about turning its grid into culs de sac without extensive use of eminent domain and other disruptive policies. O’Toole is correct that the grid owes its origins to authoritarian regimes and that today it’s embraced by city planners in the Smart Growth and New Urbanist schools. But while culs de sac may have originally appeared in organically developed networks of streets, today’s culs de sac promoted by traffic engineers are hardly a free market outcome. As Daniel Nairn has written, the public maintenance of what are essentially shared driveways “smacks of socialism in its most extreme form.” Some studies have found that culs de sac experience less crime relative to nearby through streets, perhaps in part because they draw less traffic. However, it’s far from clear that a pattern of suburban streets makes a city safer than it would be would be with greater street connectivity. Some studies find that street connectivity correlates with greater social capital. O’Toole’s promotion of social engineering through culs de sac to create a localized drop in crime at the expense of a city’s residents’ social capital is […]

Yesterday, the Mercatus Center released the third edition of Freedom in the 50 States by Will Ruger and Jason Sorens. The authors break down state freedom among regulatory, fiscal, and personal categories. At the study’s website, readers can re-rank the states based on the aspects of freedom that they think are most important, including some variables related to land use and housing. The available variables include local rent control, regulatory takings restrictions, the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index, and an eminent domain index. Using only these “Property Rights Protection” variables, Kansas ranks as the freest state, followed by Louisiana, Indiana, Missouri, and South Dakota. Texas, sometimes cited as the state without zoning, comes in at 18th. The least free state is New Jersey, with Maryland at 49th, followed by California, New York, and Hawaii. This result — states with some of the most expensive cities being the most regulated — is unsurprising. In the places with the freest land use regulations, where a developer would be able to build walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods without going through a burdensome entitlement process, there isn’t demand for dense development. This may be one reason why the Piscataquis Village project, an effort to build a traditional city, is happening in a sparsely populated Maine county because new development of this sort is simply not permitted near any population centers. As Stephen recently pointed out, public opinion in New York tends to see city policies as wildly pro-development: In spite of the popular impression of New York as a builder-friendly city that’s constantly exceeding the bounds of rational development, the city’s growth over the past half-century has been anemic, and has not kept pace with the natural growth in population. This ranking of New York near the bottom of the index demonstrates what urban economists already know — new development […]

Yesterday at Slate Matt Yglesias pointed out the poor logic behind AAA’s opposition to the elimination of some parking minimums in the DC zoning reqrite. AAA is not alone, joined by many DC residents who oppose the rewrite that will introduce some deregulation in parking requirements and zoning. The rewrite includes a few basic changes, and Greater Greater Washington provides excellent coverage of each: Eliminate parking requirements for some transit-rich neighborhoods Permit homeowners in some neighborhoods to rent out accessory dwellings such as basements or carriage houses Remove the 30-foot width requirement for developing alleyway homes Allow more cornerstor commercial development in residential neighborhoods Simplify the Planned Unit Development approval process Initially, the plan included a proposal to switch from parking minimums to parking maximums, but fortunately this proposal was rejected in favor of allowing developers to build parking based on what they think will be profitable, allowing for a freer market in parking. Now, those who assert that eliminating subsidies to driving amounts to a “war on drivers” are left without basis for their argument. I am not too enthusiastic about the zoning rewrite because it doesn’t go nearly far enough in permitting a greater supply of housing. It makes no significant changes to allowable floor area ratios, only permitting greater density by tinkering around the edges. However, as the zoning update is focused on simplifying the zoning map and allowing some increased freedom for developers to build what they think consumers want, it is in many ways a step toward market urbanism. It will benefit some homeowners and their renters by permitting accessory dwelling rentals. Additionally the attempt to simplify the Planned Unit Development process could improve rule of law in DC development and take steps toward leveling the playing field for developers. Perhaps the most significant element […]

A recent Wall Street Journal op ed combines two of my favorite topics: Franz Kafka’s The Trial and the inefficiencies of zoning. Roger Kimball explains the roadblocks he has faced in trying to repair his home after it was damaged in Hurricane Sandy. He writes: It wasn’t until the workmen we hired had ripped apart most of the first floor that the phrase “building permit” first wafted past us. Turns out we needed one. “What, to repair our own house we need a building permit?” Of course. Before you could get a building permit, however, you had to be approved by the Zoning Authority. And Zoning—citing FEMA regulations—would force you to bring the house “up to code,” which in many cases meant elevating the house by several feet. Now, elevating your house is very expensive and time consuming—not because of the actual raising, which takes just a day or two, but because of the required permits. Kafka would have liked the zoning folks. There also is a limit on how high in the sky your house can be. That calculation seems to be a state secret, but it can easily happen that raising your house violates the height requirement. Which means that you can’t raise the house that you must raise if you want to repair it. Got that? Disaster rebuilding efforts highlight the impediments that bureaucracies create for economic development, but they are far from the only time that land use regulations create kafkaesque obstacles for property owners. In The High Cost of Free Parking, Donald Shoup explains that parking requirements can create a similar effect. When a business owner goes out of business and wants to sell his property, it’s likely that the next owner will want to operate a different type of business in the location or that parking requirements will have […]