Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

As proposed, Moreno's 15-minute city has no chance of implementation, because economic and financial realities constrain the location of jobs, commerce, and community facilities. No planner can redesign a city by locating shops and jobs according to their own whims.

Promotors of recently developed cities ranging from Nusantara, the freshly built capital of Indonesia, to Neom, Saudi Arabia’s futurist urban paradise, advertise them as breakthroughs in urban living. But does the world need new cities?

Kevin Erdmann offers a helpful corrective to the “YIMBY triumphalism” of claiming that large relative rent declines in Austin and Minneapolis are results of YIMBY policies. He’s mostly correct, especially about the rhetoric: arguing about housing supply from short term fluctuations is like arguing about climate change based on the week’s weather. Keep your powder dry, promise slow change and long-term stability, and recognize that demand shocks are responsible for most fluctuations. But Erdmann makes a stronger claim: Supply has never and will never cause a collapse of prices and rents. It causes stability. Is that true? In a case like Austin or Phoenix, sure: prices are not too far above the cost of construction, and abundant supply cannot (durably) push the price of new housing below the cost of construction. But YIMBY has more to offer to San Francisco, Auckland, or London. In those cases, prices are far above construction cost. That means that even when demand is relatively soft, there’s money to made in construction. As Erdmann allows: After a decade of more active construction in Auckland, rents appear to be 10% to 15% below the pre-reform trend. That’s a big win. After a decade. That’s what success looks like. That’s the promise – 5 to 15% relative rent declines, decade after decade. But there are several good reasons to believe this won’t happen in an even, steady pattern, at least not all the time. Hopefully by 2040 we’ll have data from several cases and be able to describe the dynamics of market restoration with much more confidence.

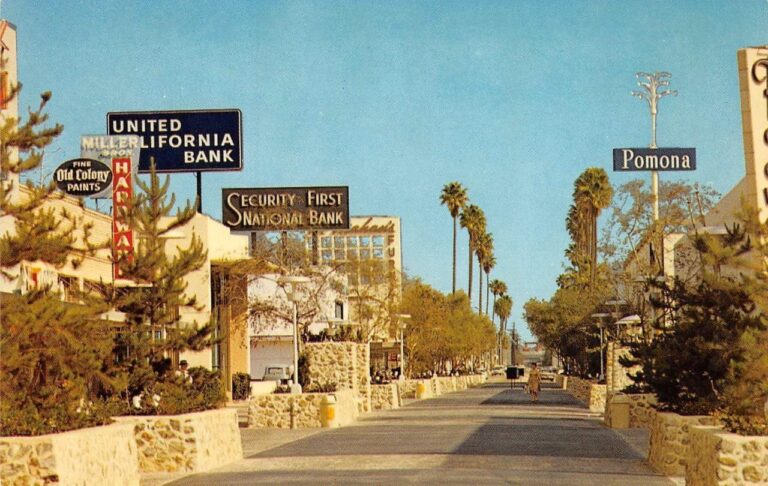

Urbanists love to celebrate, and replicate great urban spaces – and sometimes can’t understand why governments don’t: But what’s important to recall – especially for those of us under, uh, 41 – is that pedestrianized streets aren’t a new concept coming into style, they’re an old one that’s been in a three-decade decline. Samantha Matuke, Stephan Schmidt, and Wenzheng Li tracked the rise and decline of the pedestrian mall up to the onset of the pandemic. Even in the urbanizing 2000s and 2010s, 14 pedestrian malls were “demalled” against 4 streets that were pedestrianized: In a 1977 handbook promoting pedestrianization, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo admit that some of the earliest “successes” had already failed: In Pomona, California, the first year [1962] the mall received nationwide press coverage as a successful model of urban revitalization; there was a 40 percent increase in sales. But the mall was slowly abandoned by its patrons, and now, after fifteen years of operation, it is almost totally deserted. A Handbook for Pedestrian Action, Roberto Brambilla and Gianni Longo, p. 25 One obvious reason for the failure of many other pedestrianized streets is that they were too little, too late. The pedestrian mall was one of several strategies against the overwhelming ebb tide of retail from downtowns in the postwar era. They weren’t seen as alternatives to driving, but destinations for drivers, who could park in the new, convenient downtown lots that replaced dangerous, defunct factories. A minority of the postwar-era malls survived. The predictors of survival are sort of obvious in hindsight: tourism, sunny weather, and lots of college students, among other things. Some of the streets which were “malled” and “demalled” have rebounded nicely in the 2000s. The slideshow below shows Sioux Falls’ Phillips Avenue in 1905, 1934, c. 1975, and 2015. The […]

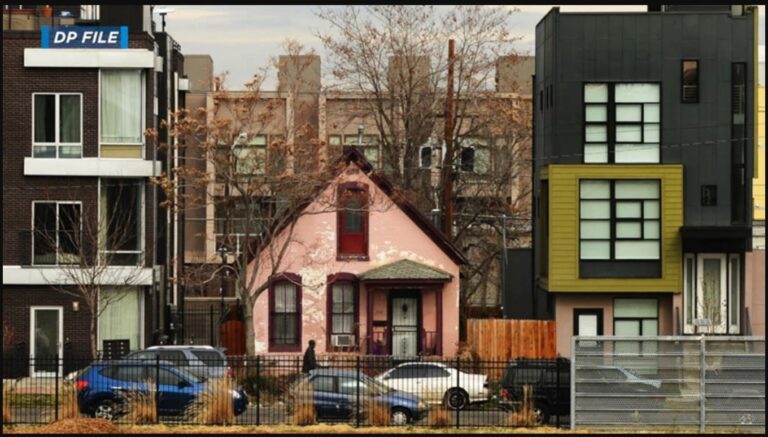

In many cities, poor people occupy valuable urban land close to downtown jobs, amenities, and transit. They can afford to live there because the housing stock in inner areas is usually older. If it hasn’t been completely renovated, the result can be quite cheap, even if the land is pretty valuable. In areas where there’s already some gentrification pressure, landlords face a timing problem: they can renovate (or sell to a developer) now, and cash out. Or they can hoard the property and wait until prices rise, supplying low-cost housing in the meantime. Land value taxes are specifically designed to penalize the hoard-and-wait approach by raising the annual tax cost of sitting on valuable land. It is specifically designed to accelerate neighborhood change. That’s the point. That’s what it says on the tin. Gentrification isn’t the only urban problem, and maybe it’s a small enough urban problem that a land value tax is a good idea anyway. But I think most of the benefits of Georgism can be unlocked with George-ish schemes (like renovation abatements or vacant land taxes) that are more narrowly designed.

Why are Max Holleran's book, Richard Schragger's law review article, and randos on Twitter all misinterpreting one important research article?

Rent control has devalued property so badly that you could make a million dollars by tearing down a nice 12-unit building in my neighborhood.

American YIMBYs point to Tokyo as proof that nationalized zoning and a laissez faire building culture can protect affordability. But a great deal of that knowledge can be traced back to a classic 2014 Urban Kchoze blog post. As the YIMBY movement matures, it's time to go books deep into the fascinating details of Japan's land use institutions.

Urbanist and YIMBY Twitter had a field day dunking on Nathan J. Robinson, whose essay in his publication Current Affairs called for building new cities in California. But California really could use some new cities - and we need to think about them in primarily economic terms.

One argument I have run across recently is that the high cost of housing is caused by mysterious corporate investors are buying up real estate and forcing up the cost. The stupidest version of this argument is that investors are hoarding all the real estate. Why is it stupid? Because corporations like to make money, and a corporation that doesn’t sell or rent out real estate is making no money from it. A more sensible version of the argument is that the existence of investors adds demand for housing, and thus that their presence thus increases housing costs.* But even if this true, are these investors really a significant factor in the housing market? In today’s Washington Post, an article supplies data for 40 metro areas. If investors are really the problem, one might think that the most expensive metros have the highest investor share. But this is simply not the case. In San Francisco, only 6 percent of for-sale houses are being purchased by investors (about the same as the 2015 share). In metro New York and Los Angeles, that share is around 10-11 percent. The most investor-heavy markets are in growing, medium-cost Sun Belt markets like Atlanta (25 percent), Charlotte (25 percent), Jacksonville (22 percent) and Phoenix (21 percent). And within those markets, investors are not buying in the most expensive areas. In Atlanta, the highest investor shares are in the lower-income Southside, and low and moderate-income southern and western suburbs. In Jacksonville, the mostly lower-income Northside and the working-class Westside have higher investor shares than the more middle-class Southside. This pattern seems to hold in less investor-heavy metros as well: even though some affluent Manhattan zip codes have high investor shares, most of the high-investor zip codes are in East Harlem, the South Bronx, and other poor […]