Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

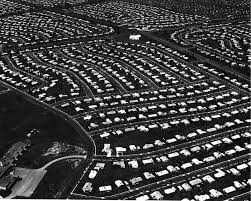

At a recent webinar, Prof. Christopher Serkin of Vanderbilt Law School made an interesting argument. He pointed out that a) Sun Belt cities tend to have less restrictive zoning than northern cities; b) Sun Belt cities also have more homeowners’ associations (HOAs) with restrictive rules; and therefore (c) perhaps zoning reform will fail because homeowners will react to restrictive zoning by creating more HOAs, which will limit density and housing supply just as much as zoning. It seems to me that this argument has some weak links. The most obvious is that it is not clear that the correlation he points out really exists. Admittedly, northern and midwestern states have fewer HOAs than the rest of the nation. In the Northeast, only 29 percent of new homes are part of HOAs, as opposed to 47 percent in the Midwest, and 2/3 in the South. But not all southern and western states are the same- and if we go state-by-state, the correlation between HOAs and strict zoning starts to disappear. In particular, California metros are notorious for strict land use regulation and high housing costs. But 64.9% of California homeowners belong to an HOA, well above the national average. In fact, only three states (Vermont, DC and Florida) have higher HOA participation rates than California. On the other hand, Texas metros tend to be less restrictive, but only 1/3 of Texas homeowners belong to a HOA. Similarly, only 15 percent of Tenneseee homeowners belong to an HOA. So its not quite clear that metros with lower housing costs and/or less zoning have higher HOA participation rates. ( On the other hand, this data would be more useful if we were able to a) distinguish between new subdivisions and the rest of the housing market, b) distinguish between HOA participation rates for […]

In this interview I talk to Onésimo Flores, Founder of Jetty, a (sort-of) microtransit company from Mexico City. Marcos Schlickmann: Thank you for participating in this interview. Please introduce yourself and talk a little bit about how Jetty came to life and what is your idea behind this project. Onésimo Flores: I’m Onésimo Flores, the founder of Jetty. I have a PhD in urban planning from MIT and a master’s in public policy from Harvard. I graduated in Law from the Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico. The idea of Jetty came about by contrasting a conflicting approach to regulation in public transportation in a place like Mexico. On one end of the spectrum, a you have a very tightly-regulated, low-quality, scarce public transport service, most of it operated by private, informal, artisanal, minibus operators, and on the other hand, ride-hailing apps, taxi apps, that had emerged not only Uber but several others, that enjoy a lot of regulatory leeway in terms of freedom to set their fares, to operate anywhere, to open the market to private individuals with spare time and spare vehicles. So, in that context, the hypothesis was that, in a way applications like Uber have made it possible to standardize a level of service: people can know what to expect, know that somebody will be held accountable if something goes wrong, know the basics of the trip, the fare and the rated quality of the driver. The level of information the passengers will get is standardized no matter who the supplier of the services is. So, the hypothesis in Jetty is that we can do something similar for collective transportation without relinquishing the economies of scale of using larger vehicles, but we do give the public access to the service improvements made possible by technology. MS: Talk a little […]

At 4:30 am, alarms on my cellphone and tablet start beeping, just enough out of sync to prompt me to get up and turn them off. By 5:00 am, I riding as a passenger along an unusually sedate New Jersey Turnpike, making friendly conversation with my driver and survey partner to make sure he stays awake. At 5:30am, as most of the city sleeps, we find a drab concrete picnic table outside the bus depot and chow down on our cold, prepared breakfasts. Around us, buses are revving up and their drivers are chatting and smoking cigarettes. At 5:50 am, we find our bus and introduce ourselves to our driver for the day. All of the Alliance drivers seem to be Hispanic. Our run begins. You wouldn’t expect it, but the first run is always the sweetest. The riders trickle on, making it easy to approach them, and unlike the typical 8:00 am rush hour rider they are usually friendly and receptive to my request. I approach them and mechanically incant “Good morning Sir/Ma’am. Would you like to take a survey on your commute today for NJ Transit? It will only take a few minutes of your time.” My partner sits in the front, tallying the boardings, exits, and survey refusals. We will spend the next eight hours zigzagging across the New York City metropolitan area, asking harried riders about their commute. For the past month or so, this has been my part-time job: surveying bus riders about their origins, destinations, and travel preferences for NJ Transit. The job is just engaging enough that I rarely have time for sleeping or class readings, but has enough slow periods that my mind can wander on the question of bus planning. Although I am not authorized to read any of the surveys […]

Caos Planejado, in conjunction with Editora BEI/ArqFuturo, recently published A Guide to Urban Development (Guia de Gestão Urbana) by Anthony Ling. The book offers best practices for urban design and although it was written for a Brazilian audience, many of its recommendations have universal applicability. For the time being, the book is only available in Portuguese, but after giving it a read through, I decided it deserved an english language review all the same. The following are some of the key ideas and recommendations. I hope you enjoy. GGU sets the stage with a broad overview of the challenges facing Brazilian cities. Rapid urbanization has put pressure on housing prices in the highest productivity areas of the fastest growing cities and car centric transportation systems are unable to scale along with the pace of urban growth. After setting the stage, GGU splits into two sections. The first makes recommendations for the regulation of private spaces, the second for the development and administration of public areas. Reforming Regulation Section one will be familiar territory for any regular MU reader. GGU advocates for letting uses intermingle wherever individuals think is best. Criticism of minimum parking requirements gets its own chapter. And there’s a section a piece dedicated to streamlining permitting processes and abolishing height limits. One interesting idea is a proposal to let developers pay municipalities for the right to reduce FAR restrictions. This would allow a wider range of uses to be priced into property values and create the institutional incentives to gradually allow more intensive use of land over time. Meeting People Where They Are Particular to the Brazilian experience is a section dedicated to formalizing informal settlements, or favelas. These communities are found in every major urban center in the country and often face persistent, intergenerational poverty along with […]

Urban Institute Press • 2005 • 494 pages • $32.50 paperback In Private Neighborhoods and the Transformation of Local Government, Robert H. Nelson effectively frames the discussion of what minimal government might look like in terms of personal choices based on local knowledge. He looks at the issue from the ground up rather than the top down. Nelson argues that while all levels of American government have been expanding since World War II, people have responded with a spontaneous and massive movement toward local governance. This has taken two main forms. The first is what he calls the “privatization of municipal zoning,” in which city zoning boards grant changes or exemptions to developers in exchange for cash payments or infrastructure improvements. “Zoning has steadily evolved in practice toward a collective private property right. Many municipalities now make zoning a saleable item by imposing large fees for approving zoning changes,” Nelson writes. In one sense, of course, this is simply developers openly buying back property rights that government had previously taken from the free market, and “privatization” may be the wrong word for it. For Nelson, however, it is superior to rigid land-use controls that would prevent investors from using property in the most productive way. Following Ronald Coase, Nelson evidently believes it is more important that a tradable property right exists than who owns it initially. The second spontaneous force toward local governance has been the expansion of private neighborhood associations and the like. According to the author, “By 2004, 18 percent—about 52 million Americans—lived in housing within a homeowner’s association, a condominium, or a cooperative, and very often these private communities were of neighborhood size.” Nelson views both as positive developments on the whole. They are, he argues, a manifestation of a growing disenchantment with the “scientific management” of […]

Every so often during his tenure as mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg tried to push through congestion pricing, in which drivers would have to pay to use city streets in Midtown and Lower Manhattan. That’s a popular solution to chronic overcrowding but, like drinking coffee to try to cure a hang over, it doesn’t really get to the heart of the matter. More intervention usually doesn’t solve the problems that were themselves the result of a prior intervention. Let me explain. In 2011, I had the opportunity to participate in an online discussion over at Cato Unbound. It focused on Donald Shoup’s book The High Cost of Free Parking, which looks at the consequences of not charging for curbside parking. If you’ve ever tried to find a parking spot on the street in a big city, especially on weekdays, you know how irritating and time-consuming it can be. It may not top your list of major social problems, except perhaps when you’re actually trying to do it. In fact, according to Shoup about 30 percent of all cars in congested traffic are just looking for a place to park. The problem though is not so much that there are too many cars, but that street parking is “free.” Except, of course, it isn’t free. What people mean when they say that some scarce commodity is free is that it’s priced at zero. Some cities, such as London, Mayor Bloomberg’s inspiration, charge for entering certain zones during business hours — with some success. (As well as unintended consequences: People living in priced zones pay much less for parking and higher demand has driven central London’s real-estate prices, already sky high, even higher). But this doesn’t really address what may be the main source of the problem: the price doesn’t […]

Cities, for most of human history, were dumb. At least, that’s what the “smart cities” movement might lead you to believe. Over the past few years, a chorus of acquisitive multinational tech corporations, trend-savvy politicians, and optimistic developers—an odd mixture of former SimCity players, in all likelihood—has come to sing of technology’s potential to solve urban problems. Through implementation of technologies like augmented physical infrastructure, central command centers, and information exchange, proponents of smart cities argue that information technology offers new solutions to old problems like trash collection, public health, and traffic congestion. While the movement’s ideological variations are many and varied, a focus on top-down smart city solutions has ultimately distracted urban observers from the bottom-up smart city revolution that’s already underway. In his 2014 book Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia, scholar Anthony M. Townsend paints a troubling picture of the former in Rio de Janeiro’s modestly titled Center for Intelligent Operations. Developed by IBM, the center acts as a hub for hundreds of surveillance cameras and sensors. At best, the center achieves little more than, in Townsend’s words, “looking smart.” At worst, the center seems to be a regression back to twentieth century centralization. Townsend’s explorations of Songdo, South Korea, a city purported to be both centrally-planned and smart, hardly quells these concerns. The discussion leaves the reader with a healthy skepticism of top-down smart city solutions. Other criticisms have made the top-down smart city feel less like something out of 1984 and more like something out of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. In a couple of recent posts, Emily points out the roadblocks presented by poor incentives and a lack of market signals, both for politicians and high-ranking public servants. For similar reasons, both parties lack the incentives to implement […]

California might have some competition in the race for high-speed rail. Texas Central Railway wants to begin construction on a high-speed line from Dallas to Houston as early as 2017. The current plan is to go from downtown to downtown, with possibly one stop along the way in College Station. An environmental impact assessment is under way and the hope is to be operational by 2021. The company claims that the price per ticket will be competitive with airfare and that the run will take a mere 90 minutes. To give that some context, current travel time from Houston to Dallas by car is about 3.5 hours according to Google (but closer to 4.5 according to my prior experience). While there’s a lot to be skeptical about here, the impact of connecting the nation’s 4th and 6th largest urban economies could be significant. If a high-speed line does get built and if it does manage to deliver on its specs (two major “ifs” already), it would be the equivalent of a magic portal…or a stargate…or a warp pipe…or a tesseract…or…well…the point being it would make the two places functionally much closer together, and that’s a big deal. Cities become economically vibrant through agglomeration. Bringing people closer together lowers search costs for both employers and employees. It also increases the likelihood of “creative collisions”. What high-speed rail could do is combine the benefits of agglomeration that each of these two cities already enjoy. And, as early in the day as it is, there’s already speculation that a line connecting Dallas and Houston would be a precursor to additional lines connecting all four of the state’s pillars of civilization: Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin. The unbridled optimist in me imagines high-speed rail as the embryonic bones of a future mega-city encompassing […]

In her new book Perverse Cities: Hidden Subsidies, Wonky Policy, and Urban Sprawl, Pamela Blais explores the impact of flat-rate fees for development charges and network services like sewer, water, and cable. She explains in detail how these little-discussed policies play an important role in shaping development and redevelopment and how the current funding of these network goods incentivizes large lot, greenfield development over infill development on smaller lots. Blais focuses her analysis on Canada and the United States. Development charges provide an easy inroad into her critique of average cost over marginal cost pricing for infrastructure. Many North American municipalities charge developers a flat-rate fee for each lot they develop. They often set this fee at the rate for lots of varying sizes, even though larger lots require more asphalt, sewer and water pipes, and cable to service them. While the cost differences may be small between one 25-foot versus one 60-foot lot, infrastructure for a new suburb of 100 houses will cost significantly more if the houses have 60-feet of frontage versus 25, but because these costs aren’t reflected in prices, residents don’t take them into account. Because the same development fee will be capitalized into each house, those who live on smaller lots cross-subsidize the services like road maintenance, garbage collection, and snow clearance of those who live on larger lots when these services are provided by local governments. Blais provides detailed accounts of how these fees shape development patterns and that the resulting sprawling development is both environmentally detrimental and expensive for cities to maintain. She points to several network services that fit a model similar to development charges: water and sewer, electricity, gas, telephone, cable television, internet connectivity, and postal service. While she cites extensive empirical evidence that the cost of delivering these services is inversely related to […]

For a libertarian urbanist blogger, I’ve always felt kind of embarrassed by my lack of knowledge about East Asian transit, considering that it’s the only place left on earth with a thriving competitive private transportation market (they even have profitable monorails!). I’ve heard good things about South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong, but it looks like Japan is really the world leader in market urbanism. I always found Japan’s post-WWII dynamism quite intriguing – despite its supposed lost decade and what I understand to be a fairly corporatist entrepreneurial model (in the end, they lost the tech innovation game to Silicon Valley), Japan has managed to remain an elite economic power. I have a (completely unfounded) theory that a lot of the dynamism comes from not having to carry the burden of a shitty, state-run transportation network and stunted land use market – as I understand it, private railway companies are pillars of the Japanese economy, similar to what the auto industry was to the US at its height. Anyway, I’ve been reading papers on Japan’s transit companies, and the first half of the abstract of this one I think sums up pretty succinctly the reasons why private transit (and, therefore, urbanism writ large) succeeds in Japan and fails in the US: In Japan, a liberalization policy was implemented over railways and buses in 2000 and 2002 respectively. Under that policy, quantity regulations for railways and buses were abolished, withdrawal regulations were eased, although fare regulations were maintained. However, even after this liberalization, institutional design remains considerably different between Japan and EU countries. An argument for competitive tendering is missing in Japan as 87.5% of rail passenger transport in the three major metropolitan areas is provided by profitable private railway companies that enjoy high social evaluation in respect to managerial […]