Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Check out Dan Bertolet’s review of the productive legislative year in Washington, where lawmakers preempted local parking, design, and unfunded inclusionary zoning requirements, among other things.

walkable suburbs have as many children as more typical suburbs

A review of a book that endorses more flexible zoning, but doesn't reject zoning entirely.

In New York City, one common argument against congestion pricing (or in fact, against any policy designed to further the interests of anyone outside an automobile) is that because outer borough residents are all car-dependent suburbanites, only Manhattanites would benefit. For example, film critic John Podhoretz tweeted: “Yeah, nothing easier that taking the subway from Soundview or Gravesend or Valley Stream.” Evidently, Podhoretz thinks these three areas are indistinguishable from the outer edges of suburbia: places where everyone drives everywhere. But let’s examine the facts. Soundview is a neighborhood in the Southeast Bronx, a little over 8 miles from my apartment in Midtown Manhattan near the northern edge of the congestion pricing zone. There are three 6 train subway stops in Soundview: Elder Avenue, Morrison Avenue, and St. Lawrence Avenue. Soundview zip codes include 10472 and 10473. In zip code 10472* only 25.7 percent of workers drove or carpooled to work according to 2023 census data; 59.6 percent use a bus or subway, and the rest use other modes (including walking, cycling, taxis and telecommuting). 10473, the southern half of Soundview, is a bit more car-oriented- but even there only 45 percent of workers drive alone or carpool. 41 percent of 10473 workers use public transit- still a pretty large minority by American standards, and more than any American city outside New York. In the two zip codes combined there are just 45,131 occupied housing units, and 24,094 (or 53 percent) don’t have a vehicle. In other words, not only do most Soundview residents not drive to work, most don’t even own a car. Gravesend, at the outer edge of Brooklyn over 12 miles from my apartment, is served by three subway stops on the F train alone: Avenue P, Avenue U and Avenue X. It is also served by […]

We identified large 91 cities and counties that regularly fail to report their building permits to the Census Bureau - including some surprising culprits.

Autonomous vehicles will cause a congestion apocalypse on downtown streets unless we price their use of the roads.

Last year disappointed pro-housing advocates in Colorado, as Governor Polis’s flagship reform was defeated by the state legislature. But Polis and his legislative allies tried again this year, and yesterday the governor signed into law a package of reforms which cover much of the ground of last year’s ill-fated HB23-213. HB24-1152 is an ADU bill. It applies to cities with populations over 1000 within metropolitan planning areas (so, the Front Range – home to most of Colorado’s major cities – along with Grand Junction), and CDPs with populations over 10,000 within MPOs. Within those jurisdictions, the law requires the permitting of at least 1 ADU per lot in any zone that permits single-family homes, without public hearings, parking requirements, owner-occupancy requirements, or ‘restrictive’ design or dimensional standards. The law also appropriates funds available for ADU permit fee mitigation, to be made available to ADU-supportive jurisdictions which go beyond compliance with the law to make ADUs easier to build (including jurisdictions not subject to the law’s preemption provisions). HB24-1304 eliminates parking minimums for multifamily and mixed-use buildings near transit within MPOs (though localities can impose parking minimums up to 1 space per unit for buildings of 20+ units or for buildings with affordable housing, if they issue a fact-based finding showing negative impacts otherwise). This bill was pared down in the Senate and would originally have eliminated parking requirements within MPOs entirely. HB24-1313 is a TOD and planning obligations bill. The bill:– Designates certain localities as ‘transit-oriented’ (if they are within MPOs, have a population of 4,000+, and have 75+ acres total either within ¼ mile of a frequent transit route or within ½ mile of a transit station – in effect, 30 or so localities along the Front Range).– Assigns all transit-oriented communities (TOCs) housing opportunity goals, which are simply […]

On March 25, the city council of Burlington, VT, voted to pass a major zoning reform that one observer of Vermont politics (X.com’s pseudonymous @NotaBot) compared to the celebrated overhaul of Minneapolis’s zoning code. Burlington – the largest city in Vermont, at 45,000 inhabitants – has not escaped the housing crisis affecting the country. Burlington was an attractive destination for new residents during the pandemic and the rise of remote work; severe flooding last year put additional pressure on the housing supply. Policymakers statewide were well aware of the challenge and last year passed S.100, a sweeping package of housing reforms. Now Burlington, led by a pro-housing mayor, Miro Weinberger, has taken action at the local level. Burlington’s reform, known as the Neighborhood Code, is a welcome simplification of the city’s zoning. The Neighborhood Code eliminates the city’s ‘waterfront’ zoning districts and a ‘dense housing overlay’, adding a higher-density ‘residential corridor’ district, for a total of four residential zones. There are also significant increases in allowed density across the city. The Neighborhood Code allows up to fourplexes in all residential districts, allows townhouses everywhere but the low-density residential zone, and expands the option to create a cottage court or add a second freestanding unit on the same lot. The new code also limits requirements for minimum lot size, lot coverage, and setbacks. The reforms took some haircuts before final passage in response to pushback from organized groups of residents, but remain a meaningful change. In their report presenting the Neighborhood Code, Burlington’s city planning department reviews the city’s history. Planners explain that much of Burlington’s housing stock predates its zoning code, and in particular many existing lots are smaller than the official minimum lot size. Also, in Burlington’s first era of zoning, the city had a single residential district which […]

In a recent report from the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, Chris Denson and J. Thomas Perdue compile the strictest minimum lot size regulations and minimum home size regulations from a range of cities and counties in Georgia. 31 of Georgia’s 159 counties mandate minimum lot sizes (in unincorporated land, on some districts) larger than 1 acre, with minimums as high as 5 acres in two southwestern Georgia counties. Charting local zoning in America is no small task, and Denson and Perdue give a valuable snapshot of one of its facets in a big and growing state. Georgia is not known for onerous regulation of homebuilding – when I volunteered with Abundant Housing LA, a fellow volunteer who’d moved from Georgia would shame liberal NIMBYs by saying how much easier it was to get apartments permitted in her conservative home state – but like much of the US, Georgia’s home construction has failed to meet the growing demand. Denson and Perdue spotlight one specific regulatory tool more typical of Georgia than elsewhere: minimum home size regulations (as distinct from minimum lot size regulations, which are ubiquitous nationwide). Denson and Perdue show that Georgia counties and county seats often require minimum home sizes far in excess of American Society of Planning Officials benchmarks, and point out this drives up housing costs significantly. Below is a map (made in ArcGIS by my colleague Micah Perry) of Denson and Perdue’s data on county government minimum home sizes, showing the highest minimum in any zone on unincorporated land for counties for which data was available: The clear lesson from Georgia’s surprisingly strict regulations is that policymakers in growing Sun Belt cities and states shouldn’t delude themselves: the crises afflicting coastal “superstar” cities are coming for them too if they don’t liberalize land use laws. Austin […]

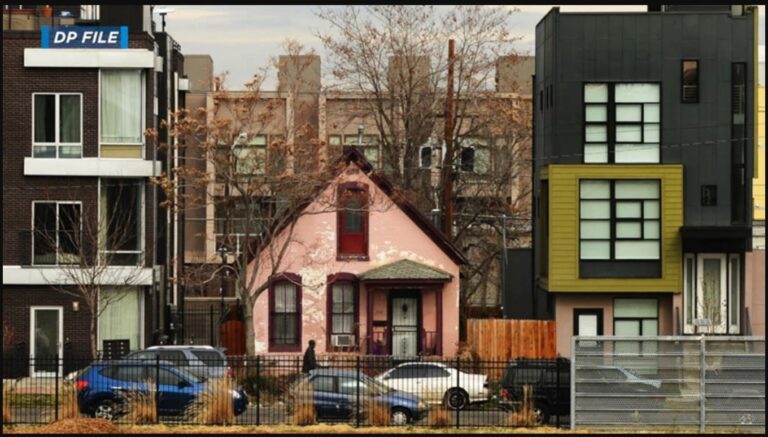

In many cities, poor people occupy valuable urban land close to downtown jobs, amenities, and transit. They can afford to live there because the housing stock in inner areas is usually older. If it hasn’t been completely renovated, the result can be quite cheap, even if the land is pretty valuable. In areas where there’s already some gentrification pressure, landlords face a timing problem: they can renovate (or sell to a developer) now, and cash out. Or they can hoard the property and wait until prices rise, supplying low-cost housing in the meantime. Land value taxes are specifically designed to penalize the hoard-and-wait approach by raising the annual tax cost of sitting on valuable land. It is specifically designed to accelerate neighborhood change. That’s the point. That’s what it says on the tin. Gentrification isn’t the only urban problem, and maybe it’s a small enough urban problem that a land value tax is a good idea anyway. But I think most of the benefits of Georgism can be unlocked with George-ish schemes (like renovation abatements or vacant land taxes) that are more narrowly designed.