Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Just 1 in 25 new apartments is owner-occupied. What happened to building condos?

Updated 1/11/24 to add 3 new papers, Wegmann, Baqai, and Conrad (2023), Dobbels & Tavakalov (2023), and Hamilton (2024). The original post was published 3/14/23. A concerted research effort has brought minimum lot sizes into focus as a key element in city zoning reform. Boise is looking at significant reforms. Auburn, Maine, and Helena, Montana, did away with minimums in some zones. And even state legislatures are putting a toe in the water: Bills enabling smaller lots have been introduced [in 2023] in Arizona, Massachusetts, Montana, New York, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. The bipartisan appeal of minimum lot size reform is reflected in Washington HB 1245, a lot-split bill carried by Rep. Andy Barkis (R-Chehalis). It passed the Democratic-dominated House of Representatives by a vote of 94-2 and has moved on to the Senate. City officials and legislators are, reasonably, going to have questions about the likely effects of minimum lot size reductions. Fortunately, one major American city has offered a laboratory for the political, economic, and planning questions that have to be answered to unlock the promise of minimum lot size reforms. Problem, we have a Houston Houston’s reduced minimum lot sizes from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet in 1998 (for the city’s central area) and 2013 (for outer areas). This reform is one of the most notable of our times – and thus has been studied in depth. For a summary treatment, see Emily Hamilton’s 2023 case study. To bring all the existing scholarship into one place, I’ve compiled this annotated bibliography covering the academic papers and some less-formal but informative articles that have studied Houston’s lot size reform. Please inform me of anything I’m missing – I’ll add it. Political economy of Houston’s reform M. Nolan Gray & Adam Millsap (2020). Subdividing the Unzoned City: An Analysis […]

For a reading group, I recently read two papers about the costs and (in)efficiencies around land assembly. One advocated nudging small landowners into land assembly; the other is an implicit caution against doing so. Graduated Density Zoning Although he’s mostly known for parking research and policy, Donald Shoup responded to the ugliness of eminent domain in Kelo v. City of New London, with a 2008 paper suggesting “graduated density zoning” as a milder alternative. Graduated density zoning would allow greater densities or higher height limits for larger parcels – so that holdouts would face greater risk. Samurai to Skyscrapers Junichi Yamasaki, Kentaro Nakajima, and Kensuke Teshima’s paper, From Samurai to Skyscrapers: How Transaction Costs Shape Tokyo, is a fascinating and technical account of how sweeping changes put the relative prices of different-sized lots on a roller-coaster from the 19th century to the present. First, large estates were mandated as a way for the shogun to keep nobles under his close control. Then, with the Meiji Restoration, the nobles were released to sell their land, swamping the market and depressing prices. The value of land in former estate areas stayed low into the 1950s. But with the advent of skyscrapers – which need large base areas – the old estate areas first matched and then exceeded neighboring small-lot areas in central Tokyo. A meta-lesson from this reversal is that “efficiency” is a time-bound concept. One can imagine a 1931 urban planner imposing a tight street grid and forcing lot subdivision to unlock value on the depressed side of the tracks. That didn’t happen; instead, the large lots were a land bank that allowed a skyscraper boom right near the heart of a very old city, helping propel the Japanese economy beyond middle-income status. We should take a long, uncertain view of […]

In the standard urban growth model, a circular city lies in a featureless agricultural plain. When the price of land at the edge of the city rises above the value of agricultural land, “land conversion” occurs. In the real world, we’re more likely to call it “development” and it is, of course, a lot more complicated. Simplification is valuable and gives us more general insights. But is greenfield development complicated in ways that are interesting and might change the results of urban economic models? Or that might change the ways we think or talk about development policy? Witold Rybczynski’s 2007 book Last Harvest helps answer these questions. It tracks a specific cornfield in Londonderry, Pennsylvania, from the retirement of the last farmer to the moving boxes of the first resident. With its zoomed-in lens, Last Harvest answers (or at least raises) lots of questions that are interesting but not especially important in the grand scheme: Why do expensive homes mix some top-line finishes with cheap, plasticky ones? Why do anti-development communities permit any subdivisions at all? What is ‘community sewerage,’ and how does it work? Exactly who thinks it’s attractive to have brick and vinyl cladding on the same house? What’s it like to buy a house from a national homebuilder? Does Chester County really produce forty percent of America’s mushrooms? The Stack Rybczynski does not use this term, but what he describes is part of what I call the “stack” of housing supply. One of the central facts of development is that it relies on a very long chain of industries and professions, each of which relies on every other part of the stack doing its job. If one part is left undone, nobody gets paid: ‘Without a water contract, we can’t get a permit for the water mains, […]

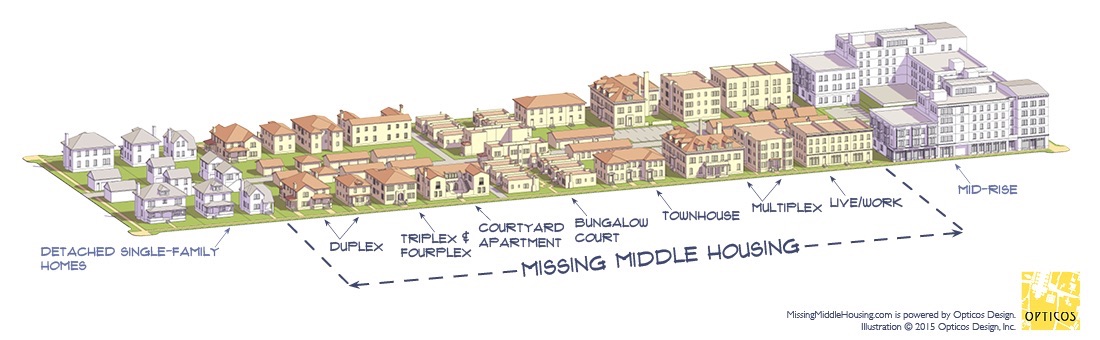

Current events being what they are, I’m happy to be writing about something positive. Once again, we’re getting an ambitious housing reform package in the California legislature. The various bills focus on removing obstacles to new housing and are a sign of the growing momentum Yimby activists have built up over the last few years. The permitting process for new housing in California is the bureaucratic equivalent of American Ninja Warrior. Localities use restrictive zoning and discretionary approvals to block new construction. When faced with state level oversight, California cities have historically leaned on bad faith requirements to ensure theoretically permitted and approved housing remains commercially infeasible. And as if that weren’t enough, “concerned citizens” can use the ever popular CEQA lawsuit to kill projects themselves (independent of direct involvements from electeds). This year’s housing package helps reduce the difficulty of getting a project through the gauntlet. Still an obstacle course, but with a few less water hazards and a slightly shorter warped wall. Still suboptimal, but directionally correct in a very big way. There are several pro-supply bills in the package, but two are especially worth calling out. SB 6 allows for residential development in areas currently zoned for commercial office or retail space. The bill would also create opportunities for streamlined approval if some portion of a proposed project site has been vacant. This last bit seems to be intended to encourage redevelopment of dead malls and similar retail heavy areas that could be better put to use as housing. SB 9 allows for duplexes and lot splits in single family zones by right. This type of missing middle housing could – at least in certain parts of California – be new housing that’s less expensive then existing stock; that’s a great outcome from a policy perspective, but […]

Everybody loves missing middle housing! What’s not to like? It consists of neighborly, often attractive homes that fit in equally well in Rumford, Maine, and Queens, New York. Missing middle housing types have character and personality. They’re often affordable and vintage. Daniel Parolek’s new book Missing Middle Housing expounds the concept (which he coined), collecting in one place the arguments for missing middle housing, many examples, and several emblematic case studies. The entire book is beautifully illustrated and enjoyable to read, despite its ample technical details. Missing Middle Housing is targeted to people who know how to read a pro forma and a zoning code. But there’s interest beyond the home-building industry. Several states and cities have rewritten codes to encourage middle housing. Portland’s RIP draws heavily on Parolek’s ideas. In Maryland, I testified warmly about the benefits of middle housing. I came to Missing Middle Housing with very favorable views of missing middle housing. Now I’m not so sure. Parolek’s case for middle housing relies so much on aesthetics and regulation that it makes me wonder whether middle housing deserves all the love it’s currently getting from the YIMBY movement. Can middle housing compete? Throughout the book, Parolek makes the case that missing middle construction cannot compete, financially, with either single-family or multifamily construction. That’s quite contrary to what I’ve read elsewhere. In a chapter called “The Missing Middle Housing Affordability Solution”, Daniel Parolek and chapter co-author Karen Parolek write: The economic benefits of Missing Middle Housing are only possible in areas where land is not already zoned for large, multiunit buildings, which will drive land prices up to the point that Missing Middle Housing will not be economically viable. (p. 56) On page 81, we learn, It’s a fact that building larger buildings, say a 125-150 unit apartment […]

I had always thought dollar stores were a nice thing to have in an urban neighborhood, but recently they have become controversial. Some cities have tried to limit their growth, based on the theory that “they impede opportunities for grocery stores and other businesses to take root and grow.” This is supposedly a terrible thing because real grocery stores sell fresh vegetables and dollar stores don’t. In other words, anti-dollar store groups believe that people won’t buy nutritious food without state coercion, and that government must therefore drive competing providers of food out of business. Recently, I was at the train stop for Central Islip, Long Island, a low-income, heavily Hispanic community 40 miles from Manhattan. There is a Family Dollar almost across the street from the train stop, and guess what is right next to it, in the very same strip mall? You guessed it- a grocery store! * It seems to me that dollar stores and traditional grocery stores might actually be complementary, rather than competing uses. You can get a lot of non-food items and a few quick snacks at a dollar store, and then get a more varied food selection at the grocery next door. So it seems to me that the widespread villification of dollar stores may not be completely fact-based. Having said that, I’m not ready to say that my theory is right 100 percent of the time. Perhaps in a very small, isolated town (or its urban equivalent), there might be just enough buying power to support a grocery store or a dollar store, but not both. But I suspect that this is a pretty rare scenario in urban neighborhoods. *If you want to see what I saw, go on Google Street View to 54 and 58 E. Suffolk Avenue in Central Islip.

Jeremiah Moss, a New York blogger, just wrote a long article complaining about the bad habits of his new neighbors in the East Village. I suspect many, if not most readers, of his article would think: maybe we need to zone out new housing to keep out the yuppies! But it seems to me that this conclusion would be wrong. Here’s why: new buildings in the East Village are generally more expensive than old buildings.* So I suspect that if yuppies are moving into old buildings like Moss’s, it is probably because they cannot afford newer buildings, or more affluent neighborhoods like Tribeca. It logically follows that if more new buildings were allowed in Moss’s neighborhood, he would have less affluent neighbors, which presumably would make him happier. *I searched listings at streeteasy.com, and found that of about 170 pre-war one-bedrooms, 77 of them (or 45 percent) rented for less than $3000 per month. By contrast, of the 32 postwar one-bedrooms in the East Village, only 3 rent for under $3000.

Alain Bertaud’s long awaited book, Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, is out today. Bertaud is a senior research scholar at the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management and former principle urban planner at the World Bank. Working through a pre-release copy over the past few weeks, I can confidently say that the book is an instant classic of the urban planning genre, and will be of significant special interest to market urbanists in particular. Rare among writers in this space, Bertaud brings an architect’s eye, an economist’s mind, and a planner’s experience to contemporary urban issues, producing a text that is theoretically enriching and practically useful. Alain and Marie-Agnes—his wife and research partner—have lived in worked in over a half-dozen cities all over the world, from Sana’a to Paris to San Salvador to Bangkok. For the reader, this means that Bertaud can speak from experience, supplementing data and theory with entertaining, real world examples and war stories. Order your copy today!

Nashville has enjoyed some of the country’s fastest job growth for several years as healthcare and tech startups have made the city home. Unsurprisingly, this economic boom has coincided with a large increase in population, greater demand for real estate, and rising house prices. But Nashville’s policy environment has moderated price increases relative to what many in-demand cities have experienced. Nashville policy has made it possible for housing developers to build both up and out in response to this new demand. However, an expansion of historic preservation efforts that have so far failed to prevent demographic change could stall the new housing supply that has maintained the city’s relative affordability. Nashville’s experience offers three lessons for other cities: 1. Legalize Housing and It Will Be Built Since 2010 the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area has grown by more than 400,000 residents, or 20 percent. Davidson County, home to Nashville at the center of the region, has grown by nearly 65,000 people, or 10 percent. Like other Southern cities, its easy to build new suburban housing in the Nashville region, and most of this population growth has been accommodated by building out. What’s unusual is that Nashville is also accommodating significant infill. In 2010 the city enacted a downtown rezoning. It eliminated parking requirements and increased by-right height limits. The new code is essentially a form-based code. Nearly all uses except for industrial are allowed in the center city. Dozens of new office, hotel, and residential towers have delivered since the new code was implemented, and many more are under construction. Since the new code has been in place, population in the two census tracts affected by upzoning has grown from about 7,500 to about 10,000. Forthcoming research from my colleague Salim Furth shows that Nashville’s recent low-density growth has been comparable to what we’d expect […]