Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In response to David Albouy & Jason Faberman’s new NBER paper, Skills, Migration and Urban Amenities over the Life Cycle, Lyman Stone asks if this means that cities will always have lower fertility? I think the answer is probably yes, but that’s extrapolating beyond the paper at hand. What this paper shows is that there will always be some regions that are a better (worse) deal for parents relative to non-parents.

First, here’s Albouy & Faberman’s abstract, with emphasis added. TL;DR: there’s no point paying to live in Honolulu if you’re going to stay at home and watch Bluey every night.

We examine sorting behavior across metropolitan areas by skill over individuals’ life cycles. We show that high-skill workers disproportionately sort into high-amenity areas, but do so relatively early in life. Workers of all skill levels tend to move towards lower-amenity areas during their thirties and forties. Consequently, individuals’ time use and expenditures on activities related to local amenities are U-shaped over the life cycle. This contrasts with well-documented life-cycle consumption profiles, which have an opposite inverted-U shape. We present evidence that the move towards lower-amenity (and lower-cost) metropolitan areas is driven by changes in the number of household children over the life cycle: individuals, particularly the college educated, tend to move towards lower-amenity areas after having their first child. We develop an equilibrium model of location choice, labor supply, and amenity consumption and introduce life-cycle changes in household compo! sition that affect leisure preferences, consumption choices, and required home production time. Key to the model is a complementarity between leisure time spent going out and local amenities, which we estimate to be large and significant. Ignoring this complementarity and the distinction between types of leisure misses the dampening effect child rearing has on urban agglomeration. Since the value of local amenities is capitalized into housing prices, individuals will tend to move to lower-cost locations to avoid paying for amenities they are not consuming.

My favorite amenity is electricity. If electrified homes were only available in a few regions, those would command a handsome premium. But because it’s available everywhere in the U.S., the amenity is free. Urbanists should aspire to make all sorts of amenities free – safe streets, school choice, and cool restaurants can become as common as indoor plumbing.

But in this context, amenities refer to things priced into regional home value – those that aren’t available everywhere. It turns out that nature is a big factor here: weather, hilliness, and oceanfront.

What happens if different people care about different amenities? They sort themselves out. At a neighborhood level, that’s pretty easy: you can live near or far from nightlife, in a walkable neighborhood or a spacious one, and still commute to the same job.

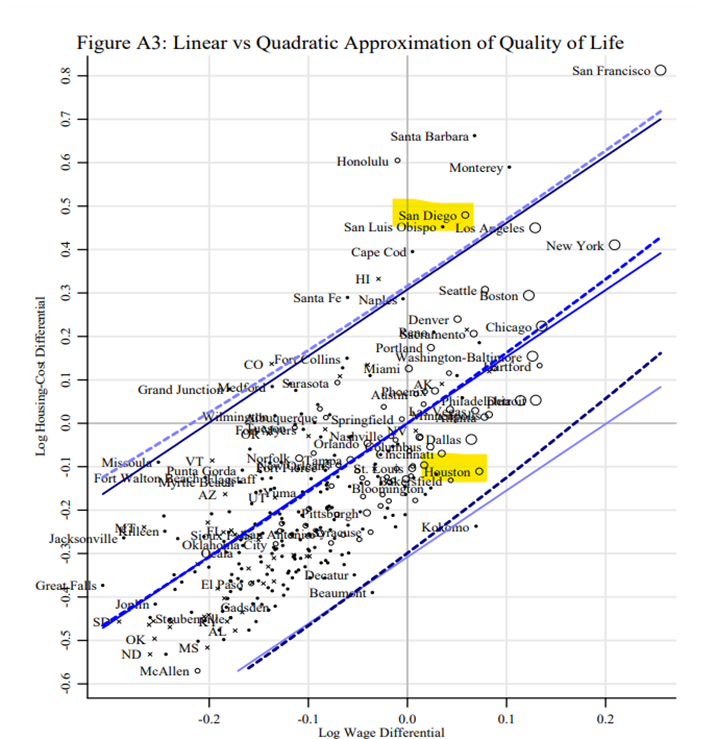

Albouy and Faberman are looking further out, at the metro region level. And the way they identify “amenities” or “quality of life” is by comparing housing costs to wages, as in this picture from Albouy’s 2012 paper:

There’s a very strong tendency for higher-wage cities to have higher housing costs. Places with surprisingly high housing costs (like San Diego and Honolulu) must therefore have something else valuable; places with surprisingly low housing costs (like Houston and Kokomo) must have worse amenities.

In this context, it’s pretty clear why parents and non-parents would value different amenities. But it’s not clear why the non-parent amenities are the ones showing up in price differentials. Why wouldn’t metro Boston, say, with its great schools be a positive outlier? Or Orlando, with its kid-friendly theme parks?

One possibility is that there are good, safe places to raise kids in almost every metro area, so that amenity – like electricity – is free. (Albouy and Faberman looked at schools and crime and found nothing; see footnote 6).

Before chasing specific amenities too far down a rabbit trail, look back at the 2012 figure again. The amenity superstars are the California coast, Hawaii, some select areas in the Rockies, and Cape Cod. Florida’s southwest coast almost makes the cut. These are places where housing demand is artificially high because they’re favored by wealthy retirees, vacationers, and the flat-out wealthy.

What does all this have to do with having kids? Albouy and Faberman assume the decision to have children is exogenous. So a household will look at the bundle of wages, prices, and amenities available in different metros (assuming that they can optimize neighborhood within a metro), and pick the tradeoff that’s best for them. Families with children spend less time outside the home, so they don’t get to take full advantage of the expensive weather in San Diego. And they need more indoor space, so Houston’s moderate costs are very attractive. Pretty obvious.

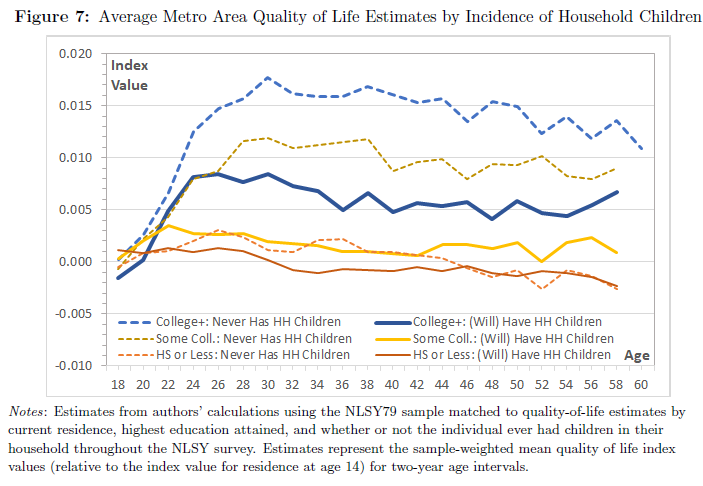

From a fertility research point of view, Figure 7 is the most interesting part of the paper. From age 24 or earlier – probably before they’ve had kids – people who will eventually have at least one child have already diverged in their residential choices from those who won’t ever have children. This is (light) evidence that fertility differences across metros are more about sorting and not causal. If your life goals include “having kids”, you don’t build a life in Miami Beach.

As I said in the intro, the general lessons of this paper probably do imply that cities will always have lower fertility than their own suburbs. Central cities usually have better kid-free amenities and worse schools and crime. It’s pretty obvious that people will sort themselves accordingly.

As to whether there’s a causal effect of cities on fertility: it depends whether one means the causal effect of being born in a central city, living in a central city as an adult, or of the mere existence of central cities as an option. None of these has been measured; they’ll all be different.