Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In a new essay for Works In Progress magazine, I explain how the familiar correlation between housing cost and homelessness works.

The most intuitive explanation would be that in high cost cities, more people lack the income for very cheap shelter. But that’s not true. Income varies more across cities than rent does. The cities with the largest numbers of near-zero income adults have low rates of homelessness.

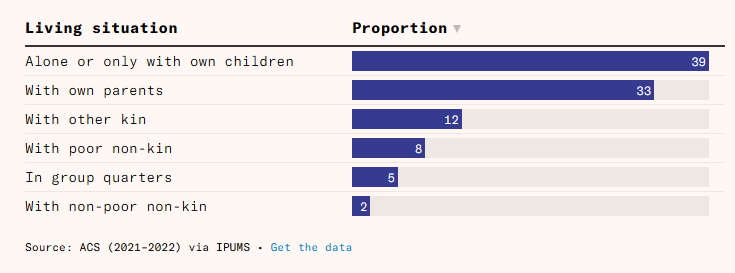

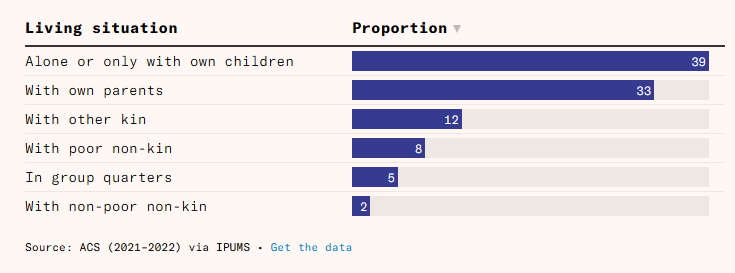

Instead, I argue that, in those cheap cities, people without incomes are mostly taken care of by their parents, other family members, and friends.

My essay has been well-received, which is a relief because I wrote it mostly out of frustration with the shortcomings of the book Homelessness Is A Housing Problem. One of those shortcomings is that authors Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern – like most homelessness scholars – fail to apply their own principles consistently.

Much of HIAHP is dedicated to a familiar & correct argument: although drugs, alcohol, and mental illness are individual risk factors for homelessness, these do not explain the prevalence of homelessness. Instead, it’s systemic factors (mainly the price of housing) that drives prevalence.

But when it comes to solutions, Colburn and Aldern stick to the academic orthodoxy of Housing First. They don’t seem to realize that the evidence in favor of Housing First is all based on analyzing it as an individual, not a systemic treatment. A typical academic study compares housing and other outcomes for homeless people “treated” with Housing First and compares them to people who received traditional treatment (or no treatment at all).

This is good and appropriate. But analytically, it is the same as identifying individual risk factors:

Heroin addiction increases your odds of entering homelessness.

Housing First increases your odds of exiting homelessness.

These are important and true! But they are not structured to help us explain the variation in homelessness rates across cities. It is possible that housing first, applied at scale, can lower the rate of homelessness. But it is not proven. Nor do individual cost/benefit estimates necessarily scale up.

Within the homelessness policy debate, my argument above will be coded as “conservative.” The critics of Housing First are politically conservative people like Michael Shellenberger and Judge Glock, and traditional homelessness-service nonprofits which have lost funding.

But I don’t necessarily think the conservatives are correct. To the extent that they blur the line between the prevalence of homelessness with its obnoxiousness, they are clearly wrong. And their contention that service generosity is a principle driver of homelessness is equally unproven (although it has at least the merit of being framed correctly).

We need more research and less dogma.