Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In 2005, Joseph Gyourko published an economic history of Philadelphia. He explored the economic and policy factors that contributed to its population and job loss during the twentieth century. Gyourko’s outlook for Philadelphia was pessimistic. He argued that the city lacked the supply of skilled labor that would allow it to adapt to the rise of the service sector. However, in the year following Gyourko’s publication, Philadelphia’s population growth rate reversed, driven by foreign immigration and college graduates choosing to stay in the city where they went to school. In spite of this growth, the city has maintained an impressive level of housing affordability.

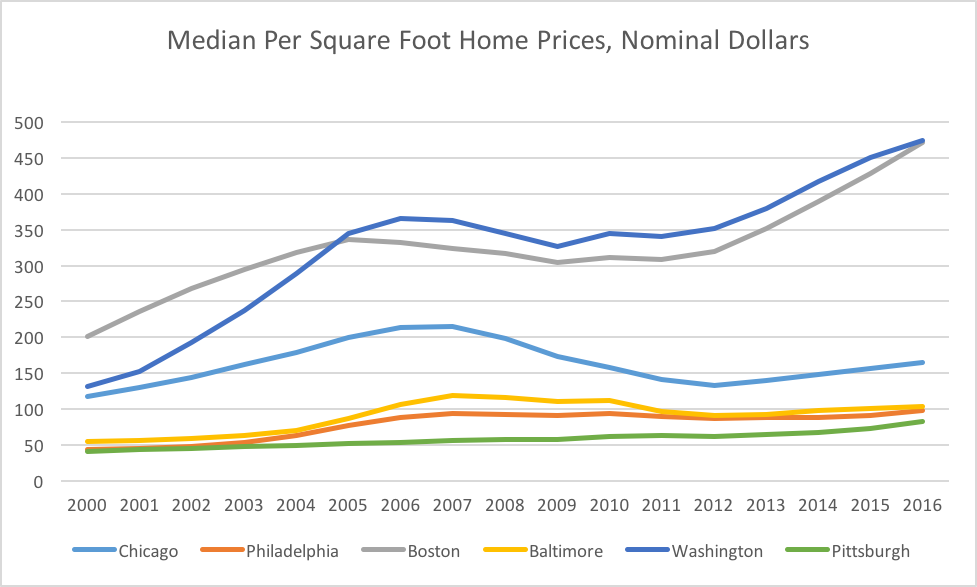

Philadelphia obviously hasn’t had the level of demand pressure other coastal cities like New York or San Francisco have seen, but since 2005, it has experienced steady population has growth from 1,400,000 to 1,550,000 people. Among potentially comparable mid Atlantic and midwest cities, only Pittsburgh has lower prices.

During its decade of population growth, Philadelphia’s home prices essentially tracked the rate of inflation. Unlike newer cities that have the option of relatively cheap greenfield development, the Census designates nearly all of Philadelphia’s neighborhood as urban, the densest designation. The city’s population growth has been accommodated through infill development and the renovation of old homes rather than through greenfield development.

It’s not the case that Philadelphia’s zoning regime accommodates as-of-right growth. Philadelphia developers have to deal with a complex web of outdated Euclidean zoning rules and myriad overlays. But developers have generally been able to get the variances they need to provide a supply of housing that keeps prices from rising in response to population growth. Philadelphia doesn’t have organized political opposition comparable to NIMBY activity in more expensive cities.

Residents’ reaction to calls for community involvement in the development process demonstrates the city’s anti-NIMBY tendencies. In 2012 the city implemented zoning code reforms with the stated goal of both increasing the percentage of development that’s built as-of-right and increasing community involvement in approval decisions. The new code formalizes standards for recognized community organizations and requires developers to give these groups notice for significant proposed projects. For projects of at least 25 units or 25,000 square feet, developers must undergo civic design review which requires them to meet with community organizations established near the project. In surveys completed in the year after the rewrite was implemented, some community group members felt that their involvement in the development process was overly burdensome, and they recommended doubling the minimum project size that would trigger civic design review. This reaction from community groups stands in stark contrast to other cities where community organizations have waged years-long wars against projects in their neighborhood.

Philadelphia’s elastic housing supply, its relatively fast approval process, and its lack of NIMBYism are all endogenous to one another. The same factors that support public policies that allow developers to respond to changes in demand with new construction are the same factors that enable its low levels of NIMBY sentiment. Because neighbors aren’t protesting each individual project, the entitlement process that facilitates and elastic housing supply is allowed to stand. Some potential factors that contribute to Philadelphia’s lack of NIMBYism include:

Contrary to Gyourko’s view from 2005, Philadelphia has not continued the decline that it experienced in the twentieth century. In spite of this growth, it’s housing stock has remained affordable. What are your thoughts about why Philadelphia has maintained its impressive level of affordability after a decade of population and job growth?

Maybe Philly’s NIMBY types left for the Mainline?

A short-term survey doesn’t reflect the on-ground dynamics of how community input has actually affected Philadelphia housing production for the worse, which for the large part hasn’t been recorded in studies. Even now, Council is still tweaking rules to RCO rules and regulations because of the deregulated, near-feudal status they’ve been given, allowing for arbitrary borders, no practical accountability, and unruly, combative meetings between racial and social groups. Councilmembers preemptively downzone vast swathes of neighborhoods with potential for multifamily as single-family townhouses because they know that the most minute variance required will trigger endless RCO meetings, which is really the basis for securing their position on Council. In reality the complaints of a “burdensome” process are heard far more from developers rather than community groups; for the minority that care deeply about development they can’t get enough meetings as it is. It’s just that the baseline level of “acceptable” development in most neighborhoods is attached SFH instead of detached.

The bottom line is that the affordability of Philadelphia is based on the same factors as Chicago’s affordability: anemic population growth coupled with even more anemic employment growth. Compared to the more normal mid-sized cities of the Midwest and Rustbelt, and not the booming coastal/Sunbelt cities, the situation is more comparable.

Chicago has lost population over the past decade. Do you think that the NIMBYism you describe will be reflected in house prices if Philadelphia keeps growing? Do you think NIMBYism is more severe in the city than in the suburbs? Housing stock within Philadelphia is growing faster than in the rest of the metropolitan area.

There are vocal and active NIMBYs in the nicer areas of the city. Take Society Hill. Also Rittenhouse. They have caused a number of projects to crater or change. Housing prices in these areas has also increased at a greater pace than the suburbs and many other cities. That said, Philadelphia is a large city geographically, and the things noted in this article hold true in many areas. At least until they don’t. Recently as gentrification spreads to North Philly, council has down-zoned certain areas to single family (not wanted higher cost multi-family buildings to “change the character” of the neighborhoods). Ultimately, it’s going to depress housing supply and drive prices up.

The effects of NIMBYism in peripheral neigborhoods will be reflected in the rents for Center City-adjacent and university neighborhoods, and not necessarily in the neighborhoods themselves. The substantial TOD that helps some Chicago neighborhoods weather even greater population decreases has largely gone unsupported in Philadelphia, at the expense of hot TOD locations in South Jersey towns and highway-oriented development in King of Prussia. For the most part NIMBYism is a bigger issue for the city than the suburbs insofar that it is a central policy issue for many politicians.

Agree that this article is a bit-misinformed. It notes that Philadelphia has no green-field development… yes, that is true, but it has huge swaths of vacant land, as a result of years of disinvestment that make it possible to build large blocks of townhouses. In addition, I have never heard anyone say that Philadelphia has less NIMBYs than New York or something. In NYC you can build a by-right 50-unit apartment building in far more areas than you can in Philadelphia. It seems in Phialdelphia everything goes up against the neighborhood associations and developers always have to trim floors and units off of their developments, because of BS density and parking concerns.

One thing this post overlooks: poverty. Even if Philadelphia’s population grew at a New York-like rate, its housing demand wouldn’t because Philadelphians have much less income to spend on housing or anything else. Philadelphia’s median household income is 41k. Even Chicago’s income is 20 percent higher!